If something cannot go on forever it will stop. – Economist Herb Stein

In July 1715, Spanish “treasure fleet” ships attempting to return home with their bounty from the Americas were slammed by a likely hurricane along Florida’s Atlantic coast. The storm sank or grounded all but one of the ten galleons in the fleet.

More than half the fleet’s 2,000 sailors died in the storm. Many of the survivors died of injuries, disease, and starvation.

Today, the wreck of one of the ships - the Urca de Lima - lies in shallow water about two miles north of the Ft. Pierce inlet. Spanish wrecks like this are the reason three modern Florida counties - Martin, St. Lucie, and Indian River – bill themselves as the “Treasure Coast”.

The Spanish galleons wrecked along Florida’s Treasure Coast were doomed without the ability to predict weather beyond a matter of hours and a few miles. Today, modern oceangoing vessels get detailed global weather conditions updated continuously. The loss of a cargo ship in a hurricane like the U.S. flagged El Faro in 2015 is rare and almost always avoidable.

The storm we’ll call Hurricane Reality hitting the global wind energy industry today is more a matter of politically driven cognitive dissonance than “surprise”. We watched it gaining strength this summer around the time Fortune Magazine released its annual Fortune 500 list of the world’s largest companies.

Ordinarily, we pay no attention to the details of Fortune’s annual list. But after this summer’s troubles for many of the world’s largest wind energy firms, we circled back to the list with a few comparisons in mind.

How did major hydrocarbon energy companies perform in 2022 vs. the world’s largest wind concerns? How are the same players performing in 2023? How have the two groups’ stocks performed over the last 3 years? And what does this suggest about near-term predictions of the decline of hydrocarbons and the future of wind energy?

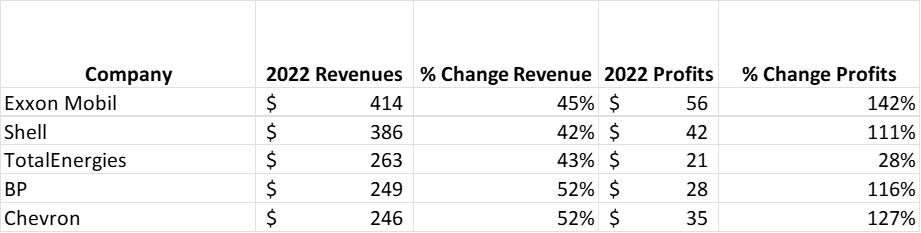

We begin with a review of the 2023 Fortune 500 rankings and the eye-watering results of the world’s publicly traded oil and gas companies. We excluded Saudi Aramco (#2), China National Petroleum (#5), and other state-owned oil and companies whose results are more easily influenced by State actions. We focused on the remaining 5 largest global oil and gas giants. For the unique situation involving BP’s divestiture of its stake in Rosneft at a loss of billions after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we express their results using their preferred “underlying replacement cost profit” for comparison.

In absolute terms (dollar amounts in billions of US$, current exchange rates):

In graphic terms:

For 2022, the five global energy firms in our analysis had an average increase in revenues of 47%, and an average increase in profits of 105%. Their average increase in profits would have been even higher but for France’s TotalEnergies “dragging down” the rest.

Exxon moved up five places in the Fortune 500 rankings in 2023, Shell moved up six spots, Total 7. BP and Chevron moved up thirteen and fourteen places respectively. Farther down the rankings, American petroleum refiner Valero, who moved up 42 spots in the 2023 rankings, saw 2022 revenues increase 58% and profits increase 1,140%. American refiner Phillips 66 moved up 37 spots in the 2023 rankings with revenues increasing by 53% and profits by 737%.

Were all these oil giants beneficiaries of tighter, more haywire global oil and gas markets due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? Most certainly. Are there other, more long-term, structural drivers that will not be resolved quickly if the war ended tomorrow? Just as certainly.

We then examined how some of the world’s largest wind energy firms performed in 2022. Like the Spanish treasure fleet right before its misfortune in July 1715, their 2022 results were mostly cloudy skies, freshening winds, and building seas.

No pure-play wind or solar energy companies have sufficient revenue to be ranked among the Fortune 500. However, for our review we included Siemens Energy (ranked #490) and GE (#167) since they are leading global producers of Spinning Green Crucifixes™ and their revenues and profits are heavily influenced by their results in these product lines. (Over the last two years, Siemens Energy fell 88 spots in the Fortune 500 rankings and GE fell 63.) Orsted, Vestas and Nordex each have revenues below $20 billion globally and are largely or exclusively wind energy firms.

Despite their smaller size, comparing changes in revenues and profits on a percentage basis between the selected hydrocarbon energy companies and these publicly traded global wind firms is directionally relevant. Again, we excluded major State-owned entities.

Only four of the five firms had any revenue growth, and for three firms the figure was 5% or less. Only Orsted saw double digit revenue growth.

Only two recorded profits for the year, with Siemens Energy, Vestas and Nordex all reporting annual losses. Orsted’s 42% increase in profits to $2 billion was one small bright spot in an otherwise dismal year for the group (but it would turn out to be short-lived). In the second half of 2022, news of the trouble brewing for the industry was widespread.

In August, Vestas announced a loss of €884 million for the first half of 2022. The firm finished the year with a loss of €1.57 billion on gross revenue of about €14.5 billion.

That same month, Reuters reported that Orsted raised its guidance for the balance of the year on the strength of its combined heating and power business. But the firm cautioned that its core offshore wind business was struggling, with core earnings from that segment coming in 33% below projections in the second quarter.

In November, Nordex reported losses of €372 million (almost 10% of sales) through nine months. On nearly flat revenues, the loss was >3.5 higher than the prior year.

In a November interview on CNBC’s Squawk Box, Siemens Energy CEO Christian Bruch blamed supply chain issues for the downturn. In the process, he let slip an often overlooked but damning aspect of wind energy, noting (emphasis added):

“Never forget, renewables like wind roughly, roughly, need 10 times the material [compared to] ... what conventional technologies need.”

In comments about how the market needed to fix things like project approval times and distributing risk between operators “who are making good profits” and equipment suppliers, Bruch gave an ominous warning:

These were the “discussions which we will need to have over the course of the next 12 months to drive this business forward.”

“But there’s no question — if we don’t resolve it as an industry, we are missing a substantial part of the energy transition, and we’ll fail with the energy transition. So, there’s no option but to fix it.”

Bruch provided no details on how the industry would change the physics and economics of wind power.

In January 2023, Reuters reported that GE’s renewable energy business reported a loss of $2.2 billion for 2022, noting that the last time the business unit made a profit (of $5 million) was the third quarter of 2020. In every quarter since, GE’s renewable energy business has lost money.

By summer 2023, it was clear that 2022 would be hard to top for the oil and gas industry. As for the five wind energy titans in our analysis, the extent to which things were going sideways wasn’t yet fully evident in their first half results.

The table below compares our five wind energy firm’s first half results for 2023 vs. 2022 (except 9 mos. for Siemens Energy whose fiscal year ends Sept. 30):

Siemens Energy shocked markets in June of this year when it announced severe problems with up to 30% of its 132 gigawatts of installed wind turbines worldwide. In disclosing that an internal review had discovered the enormous magnitude of the problems, Siemens Gamesa CEO Jochen Eickholt stated, "I have said several times that there is actually nothing visible at Siemens Gamesa that I have not seen elsewhere. But I have to tell you that I would not say that again today." The stock cratered 37% overnight.

Two months later Reuters reported the company had taken a resulting €2.2 billion charge against earnings That month Germany’s Manager Magazin reported a special committee (including CEO Christian Bruch and board members) had conducted simulations and found the cost of the problems could be almost three times as high as the recorded charges.

This July, Avangrid, the developer of the Commonwealth Wind project off the coast of Massachusetts, agreed to pay over $48 million to three of the state’s utilities to abandon the project. Avangrid is a U.S. subsidiary of Spanish renewable energy darling Iberdrola.

In late July, GE announced a $359 million loss for its Renewable Energy division for the first half of 2023, a slight improvement over the prior year’s $419 million loss . The loss came despite a healthy 24% increase revenue and slight margin improvement over the same period in 2022.

In August Orsted got in on the fun, announcing potential impairments of $2.3 billion due to “supply chain problems, soaring interest rates and a lack of new tax credits”. Orsted shares plunged more than 20%, to a level almost 70% below its 2021 peak. One week after Orsted dropped the bombshell, its CEO threatened to walk away from its U.S. projects absent additional financial support from the Biden administration (read: American taxpayers), commenting “we are still upholding a real option to walk away.”

In early September Shell-Ocean Winds, joint venture developers of the SouthCoast offshore wind project, agreed to pay utilities $60 million to terminate their supply contracts and abandon the projects. It was the second such offshore wind project abandoned by major developers off the coast of Massachusetts in the space of less than sixty days.

By comparison, the five major oils highlighted in our analysis were not exactly printing money at the same rate they had been in 2022, as the chart below depicts:

However, in absolute dollars, every one of the five major oil and gas companies was still wildly profitable by comparison to their wind industry counterparts. First half profits ranged from $7.5 billion (BP) to $19 billion (ExxonMobil).

Looking back on “old” energy vs. “alternative” energy since the world began to crawl out from under the Covid-19(84) pandemic in early 2021, we find an unmistakable pattern. The figure below charts 3-year stock prices for Exxon Mobil, BP, Shell, TotalEnergies, and Chevron.

The next chart shows the stock performance for our five wind energy firms - Siemens Energy, GE, Vestas, Orsted, and Nordex - over the same period. With the exception of GE (whose jet turbines and other diversified businesses offset losses in its Renewable Energy division), the performance of the wind energy group by comparison is awful.

One of the most revealing episodes involving the “wind is cheaper”, “Levelized Cost of Energy”, “Social Cost of Carbon” mirage of the last several years occurred in June in New York. The developers of four offshore wind projects petitioned the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) for dramatic price increases for power generated by projects yet to be built under contracts signed several years ago.

In its petition, Sunrise Wind (an Orsted and Eversource joint venture) claim exogenous events (Covid-19, supply chains disruptions, inflation, interest rates) as the basis for the requested ex post facto adjustments. The developers of Empire Wind 1 & 2 and Beacon Wind – a joint venture of BP and Equinor – also claim their petition is due to the same “numerous exogenous factors”.

In fact, a search of the terms “inflation”, “supply chain”, “interest rates” and “pandemic” in the two heavily redacted petitions returns the following rather comical results:

NYSERDA analyzed the petitions and provided their own estimates of the requested price increases. The heavy increases we would be borne by New York electricity ratepayers (and we suspect in some way or another, partly by U.S. taxpayers):

The petitions come on the heels of wind energy receiving over $50 billion in subsidies in the U.S. over just the last 12 years. In 2014, Berkshire Hathaway (parent of Iowa wind power firm Mid-America Energy) CEO Warren Buffett said (emphasis added):

"On wind energy, we get a tax credit if we build a lot of wind farms. That's the only reason to build them. They don't make sense without the tax credit."

We conclude with a largely forgotten but relevant fact about one of the five wind energy firms in our story. Dansk Naturgas was the Danish state oil and gas company founded in 1972 to manage Denmark’s oil and gas resources in the North Sea. The company was later renamed to Danske Olie og Naturgas A/S, known as Danish Oil and Natural Gas (DONG).

After 2000, the firm grew through acquisitions in electricity generation and public utilities. It acquired interests in natural gas fields, which led to a series of long-term gas supply contracts (one ironically involving Gazprom, Russia, Nordsteam 1 and Germany). Then, the company changed direction.

In 2009, Denmark was host to the annual UN “Conference of the Parties” (COP-15) meeting on climate change. Around that time, the company boldly embarked on a plan to become a renewable energy firm focused on offshore wind. By 2014 the firm divested its last onshore wind projects and a year later had 3,000 megawatts of installed offshore wind capacity.

On September 29, 2017, DONG sold off its last oil and gas interests to UK conglomerate Ineos. Announcing its successful transition to renewable energy was complete, DONG changed its name to Orsted, after Danish scientist Hans Christian Orsted (first to discover the connection between electricity and magnetism).

In under four years, Orsted rode the subsidy-fueled “alternative energy” Green Grift wave from a market capitalization of under $25 billion to almost $100 billion. After January 2021, the wheels started to come off.

A graph of Orsted’s stock price from their transformation to an offshore wind-centric energy company to today shows that the firm has given back nearly all of its gains in market capitalization since the transformation.

How do we view these developments in light of the International Energy Agency (IEA) and others’ forecasts of peak oil consumption this decade, and the importance wind energy will supposedly play in the “energy transition”?

Oil is “sticky” so to speak because it is extremely valuable to society. As such, it’s not likely to go anywhere anytime soon. Like every other energy source, it has its pros and cons.

As for wind energy, while we predict it will continue to be portrayed as a “free, clean” panacea for climate change, the solution to our energy problems, and subsidized to the moon in the short-term, Hurricane Reality is rapidly approaching. The industry will beg for more subsidies, threaten to walk away from additional projects, and absorb hundreds of millions of penalties to do so.

In the process, there will be capital destruction, lost opportunity cost, and no shortage of “exogenous circumstances” used as excuses to explain the wreckage. But unlike the Spanish treasure fleet wiped out on the Florida coast in 1715 with no ability to see what was coming, this time the governments who funded the sunk concerns won’t be able to claim they were blind to the signs of the approaching storm.

A few gems will be salvaged from the wreckage. But for the most part, there will be nothing left behind to attract tourism like Florida’s Treasure Coast. And instead of treasure buried at sea, most of the destroyed capital will be plainly visible on the surface, with no one even bothering to hunt for it.

“Like” this post or be assigned to guard a wind turbine landfill. “Share” and spread it, to help us grow (especially since we’ve ditched Twitter/X). And keep your comments coming! We love them!

In my opinion, the Root cause of the "Renewables Madness" is Public Indoctrination and misinformation on energy, compounded by poor energy education. Worse yet, the non energy savvy politicians are either funded by Environmental NGO's or they are recycled from environmental activist groups. Here is my take on this: http://dickstormprobizblog.org/2023/09/21/please-wake-up-america-your-energy-and-electricity-generation-reliability-are-at-risk/

Who is Warren Buffett?

In 2014, Berkshire Hathaway (parent of Iowa wind power firm Mid-America Energy) CEO Warren Buffett said (emphasis added):

"On wind energy, we get a tax credit if we build a lot of wind farms. That's the only reason to build them. They don't make sense without the tax credit."

Excellent article from environMental on Substack. Engaging and enlightening. One person asked “There’s no easy answer, or ‘clean alternative’ is there?”

That person should know that the history of oil, coal and natural gas were not easy. Oil and coal are far easier and cleaner now than they were at the start of industrialization. Thousands of men died in mines. The idea of fracking was born in 1862, yes, 1862. The first commercially viable fracking operation came on stream in the early 2000s.

Your title, “Hurricane Reality” is particularly apt. It compares most favorably with what could be classified as the Jiminy Cricket syndrome, also known by its title song;

When you wish upon a star Makes no difference who you are Anything your heart desires Will come to you

It’s heroic to fight an enemy who doesn’t believe in facts. You probably know that, too. Keep up the great work.

Oh, and to answer the initial question, you may agree that Warren Buffett is a relative of Orren Boyle.