NVDA Gets Pricey

The North Dakota jury renders a verdict in favor of Energy Transfer Partners. The accompanying award is a real "existential crisis" for Greenpeace.

“The dildo of consequences rarely arrives lubricated.” – (author unknown)

NVDA is the stock symbol for Nvidia, the world’s most valuable microchip manufacturer. The stock may or may not be pricey, but that’s not what this story is about.

NVDA also stands for “non-violent direct action,” a form of demonstration championed by “environmentalists” in America and Europe, and given wide latitude to push the legal boundaries of “non-violent” civil protest. Until last week, that is, when a North Dakota jury defined those boundaries, and imposed significant consequences for exceeding them on the defendant parties against whom they ruled.

Last week’s verdict in that North Dakota case portends a shift in how environmental activists target, engage in, support and fund “NVDA” in America. Ironically, for the defeated defendant – whose actions were motivated by the premise that “climate change is an existential crisis” - it also created an actual existential crisis, economically speaking.

What happened last week that caused the ground to shake under environmental activists’ feet and the environmental non-governmental organization (ENGO) Hydrocarbon Hate Machine™? How serious is the threat to the defendant parties who lost the case, and what happens next? And given other recent cases involving environmental activists, is there a trend here?

We begin our story by defining “non-violent direct action” (NVDA). Merriam-Webster’s definition works for our purposes and breaks the term down into its constituent parts.

Nonviolent: abstaining or free from violence.

Direct action: action that seeks to achieve an end directly and by the most immediately effective means (such as a boycott or strike).

Merriam-Webster’s definition of violence is also relevant (emphasis added): the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy. The definition clearly implies the target of force can be either humans (“injure”) or property (“damage or destroy”).

We asked Grok 3 AI to define NVDA. The answer it returned could not have been more ironic in relation to this essay, the key components of which are shown below (emphasis added):

Non-violent direct action refers to a strategy of protest or resistance where individuals or groups actively intervene in a situation to achieve a specific social, political, or environmental goal, without resorting to physical violence or harm against people.

Examples include sit-ins, blockades, marches, or symbolic stunts—like Greenpeace activists boarding oil rigs or chaining themselves to equipment—designed to pressure decision-makers or shift public opinion. It’s distinct from passive resistance (e.g., simply refusing to comply) because it’s proactive, directly confronting the target issue, yet it avoids violence, distinguishing it from riots or sabotage. Effectiveness often hinges on visibility and public sympathy, as seen in the Dakota Access Pipeline protests, where tactics like encampments and road blockades aimed to halt construction without physical attacks, though tensions sometimes escalated due to external responses.

Regarded as the world’s most well-known environmental activist organization, Greenpeace has proudly touted its use of NVDA for decades. The term appears in communications from the parent organization going back to at least 2014 (this example from founder Rex Weyler) and its national/regional organizations in the U.S. (here and here), UK, Europe, Canada and Africa.

In its latest Annual Financial Report (2023) Greenpeace International (GPI), a Dutch foundation based in Amsterdam with the formal name Stichting Greenpeace Council, describes the global organization’s structure as follows:

“Greenpeace is an independent global campaigning network, consisting of 25 national and regional Greenpeace organisations (NROs) and Stichting Greenpeace Council/Greenpeace International (GPI) as a coordinating and supporting organization.”

The national organization in America is known as Greenpeace USA, but it is actually made up of two different legal entities. Greenpeace Inc. is a 501(c)(4) nonprofit organization, a “social welfare organization.” That status allows it to engage in lobbying and advocacy and organize campaigns and stage protests, and engage in actual NVDA. Because of its lobbying activities, donations to Greenpeace Inc. are not tax deductible.

Greenpeace Fund Inc. is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, a status which limits its lobbying ability but allows it to focus on education, research, and grant-making. The status also allows tax deductibility for donations by U.S. donors. The entity channels money to Greenpeace Inc and other NRO’s for their charitable and educational work but does not directly engage in on-the-ground NVDA.

Think of Greenpeace Inc. as the entity that gets its hands dirty with NVDA and policy fights, and Greenpeace Fund Inc. as the entity that finances the machine, raising and distributing funds on a tax-deductible basis behind the scenes.

Many readers will remember the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) in North Dakota in the 2016-2017 era. In July 2014, Energy Transfer Partners (Energy Transfer) announced the development of the DAPL. Two years of careful route planning and environmental assessments ensued, across a variety of key concerns such as cultural sites and historic values, working with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and North Dakota State Officials.

As a result of that careful planning, ~97% of DAPL’s route would cross private land. An exception is where the DAPL would cross the Missouri river under a reservoir called Lake Oahe.

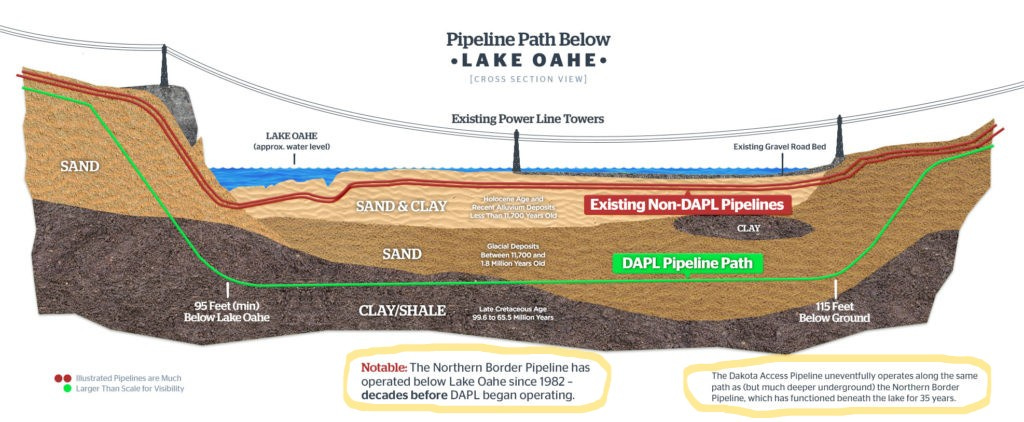

The land immediately adjacent to the river on both sides of the crossing is federal land under the jurisdiction of USACE. The specific crossing was chosen because the DAPL could be placed in the narrow corridor of an existing oil pipeline to minimize environmental impact as well as risks and impacts to historic resources or cultural features.

For reasons requiring no explanation to readers of this publication, DAPL faced strong opposition from the usual cadre of environmental groups soon after Energy Transfer announced the plans and started construction. With the overwhelming majority of the project being constructed on private land, that opposition needed a more public focal point.

The 1,172 DAPL route crossed thirty or so miles of federally regulated waters, including rivers, streams, and dams—most notably under Lake Oahe, a Missouri River reservoir near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. This not only became the necessary focal point but triggered a requirement under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) for either an Environmental Assessment (EA), or an Environmental Impact Study (EIS).

When USACE issued the final EA for the DAPL Missouri river crossing under Lake Oahe near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation on July 25, 2016, the project became the focal point for protests and the latest frontline battle in America for environmental activists and ENGO’s.

Two facts are instructive. First, DAPL was never going on, over, through or under Standing Rock Sioux Tribe reservation land. As we noted, most of the project was completed on private land. The location of the pipeline crossing over Lake Oahe and in relation to Standing Rock Sioux Tribe reservation land is shown below.

Second, with the benefit of horizontal drilling advances, DAPL was constructed well beneath Lake Oahe, in the existing Northern Border Pipeline corridor. The Northern Border Pipeline has been in operation since 1982.

What started as a small civil protest in April near Cannon Ball, North Dakota, when members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe established the Sacred Stone Camp to oppose the pipeline’s crossing under Lake Oahe near the tribe’s reservation, quickly devolved into a form of “direct action” that was anything but “non-violent” after the EA was issued.

Greenpeace was involved, as was a group formed specifically for the DAPL protests called the Red Warrior Society (RWS). Whereas Greenpeace openly advocates NVDA, RWS describes its style in different terms: “militant direct action.”

After the EA was issued, between late August 2016 and early 2017, what began as a small group of local and regional protesters were joined by hundreds, then thousands of others (mostly recruited Astroturf protesters from outside the area). Many were peaceful. Some were not.

We were not there. We do not judge. Frankly, our opinion is irrelevant in this case.

The DAPL mayhem ended when the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe asked the protesters to leave (not enough “N” in the NVDA) and the last were evicted in February 2017. Construction at the Lake Oahe crossing was completed quickly thereafter and before the first hints of fall, DAPL was transporting crude oil. But, after suffering delays, property damage, loss of investors and increasing borrowing costs in the hundreds of millions of dollars resulting from the protests, Energy Transfer was not done with the matter.

In March 2019, Energy Transfer filed a lawsuit in a North Dakota state court against Greenpeace International and its U.S. entities as well as RWS aka “Red Warrior Camp” and certain individuals. The complaint alleged the defendants were responsible for financial harm by disrupting and preventing its construction and completion of DAPL and maliciously defaming it with project financiers at great cost, as well as physically harming its employees, contractors, equipment, and infrastructure. The suit accused GPI and U.S.-based Greenpeace Inc. and Greenpeace Fund Inc. of:

“…violent attacks on Energy Transfer employees and property, soliciting money for and providing funding to support these illegal attacks, inciting protests to disrupt construction, and a vast, malicious publicity campaign against Energy Transfer.”

In retrospect, Greenpeace might have given more consideration to the jurisdiction. But in the high cotton days of “climate change” activism, after tying up Keystone XL and in the wake of the global Paris Agreement, “environmentalist” protesters and ENGOs rode a temporal wave of popularity and “wins” all the way to a misplaced overconfidence that their self-adjudicated moral authority would somehow outweigh any legal authority. As Doomberg noted in Finding Out days ago:

North Dakota would thus seem a suboptimal place to launch a campaign of “militant direct action” against a proposed oil pipeline—one marked by allegations of trespassing on private property, destroying construction equipment, and assaulting employees and contractors. Using improvised explosive devices to attack police would also seem unwise, as would deploying hacked information to threaten officers and their families. Killing the livestock of local farmers and ranchers as part of an intimidation operation could land you in a spot of bother—just as using Facebook to instruct others on how to murder security guards might.

It is common for plaintiffs to dramatize their complaints before the court. We do not judge the veracity or merits of Energy Transfer’s claims in its litigation against the Greenpeace and Red Warrior Society Defendants. Below are a few screenshots from the complaint showing Energy Transfer allegations against RWS and Greenpeace.

About RWS, Energy Transfer stated:

About Greenpeace’s involvement in training and funding the admittedly militant RWS and Red Warrior Camp:

Energy Transfer provided specific examples and dates of actions. Whether portrayed by ET factually or not, few would have difficulty distinguishing whether such activities could reasonably be called “non-violent direct action” vs. “militant direct action.”

Next are three specific examples of something that, no matter what the hell you want to call them, clearly are not “NVDA.” In August:

In September:

Continuing into October:

Energy Transfer alleged in the complaint that while these actions were occurring in fall of 2016, Greenpeace continued to raise funds – inside the U.S. and beyond – for RWS and Red Warrior Camp with full knowledge the funding, training and support were being used for activities that went well beyond “non-violent direct action”.

Whether Energy Transfer’s allegations are true or false was a matter for the jury. But Greenpeace pled its case in the court of public opinion preemptively.

In March 2024 Greenpeace USA published 6 Reasons Why Energy Transfer’s Lawsuit Against Greenpeace Is Outrageous. (Their website provides a compendium to case documents with links.) About a month prior to the North Dakota court rendering its verdict, the ENGO published an open letter to Energy Transfer signed by 450 supporters around the world.

Images, publicly available information, and even Greenpeace’s own website and Red Warrior Society’s own social media posts lend credibility to Energy Transfer’s allegations. They certainly did not help the defendant parties’ case.

For example, on the question of whether Greenpeace helped raise funds for Red Warrior Camp, this September 2016 article was still up on the ENGO’s website at the time of publication:

As evidence that RWS and Red Warrior Camp “protesters” were willing to resort to the most severe forms of force and violence in order to stop DAPL, the complaint incorporated protesters own social media posts (Does “by any means necessary” sound familiar?)

A visual example of the “militant direct action” in which RWS and Red Warrior Camp engaged - and Energy Transfer alleged Greenpeace funded - comes via this AP photo from October 28, 2016 (the day after the October 27th incident referenced in one of the complaint screen shots we included above):

The complaint also alleged coordinated efforts by the defendants to target Energy Transfer’s banks and lending facilities, misleading project financiers with false stories about violating Standing Rock Sioux Tribe rights and falsely representing that DAPL goes through the Tribe’s reservation land. Some of these succeeded, with specific banks, amounts and dates listed in the complaint.

In essence, Energy Transfer asked a Morton County, North Dakota jury to decide whether an ENGO who trained, supported, and funded violent actions against people and property (despite claiming to only support “NVDA”), malevolently and knowingly defamed its reputation with financiers with falsehoods, and openly raised money in support of – and with full knowledge of – such actions can be held liable to a corporation under state laws.

By summer 2024 Greenpeace International, clearly angry, and likely growing scared of the potential outcome in the North Dakota case, sought relief through the Dutch courts. In a letter dated July 23, 2024, lawyers for Greenpeace International put Energy Transfer on notice of their intent to hold them liable under the European Union’s new Anti-SLAPP Directive (which had just come into effect in early May of that year), demanding that the company withdraw the North Dakota lawsuit and pay the ENGO’s legal costs incurred. Energy Transfer’s attorneys politely declined the offer in their September 2024 response. And so it was that on February 11, 2025, Greenpeace initiated the first test of the EU Anti-SLAPP directive, issuing a summons to Energy Transfer a few weeks before the jury began deliberating the North Dakota case.

On March 19, 2025, in Mandan, North Dakota, a Morton County jury of nine found the Greenpeace entities liable to Energy Transfer for nearly $667 million in compensatory and punitive damages for their “non-violent direct actions.” The verdict should, at the very least, cause some serious introspection among environmental activists in America and Europe.

A precise allocation of damages for which each of the three Greenpeace entities is responsible will not be in the public domain until the judgment order is finalized. Based on Greenpeace’s own statements and some legal analyses, here is what we suspect.

The $667 million award far exceeds the $300 million Energy Transfer had sought. Reuters reported the award includes $400 million in punitive damages. Some legal experts have inferred from the total award and relative scope of each Greenpeace entity’s liability that U.S. entity Greenpeace Inc. is likely responsible for over $400 million of the damages. The remaining amounts are likely shared by Greenpeace International (estimates ranging from $100 million to $150 million) and U.S. tax deductible funding entity Greenpeace Fund Inc. (~$100 million, or less). If roughly accurate, that would mean the Greenpeace USA entities are responsible for approximately $500 million of the damages award.

Greenpeace posted a response to North Dakota verdict on its website. They promise to appeal but their spirited wording downplays the chances of success, especially given the political makeup of the state, something Doomberg wisely noted in Finding Out.

Greenpeace clearly recognizes the seriousness of the economic implications of the defeat and the appeal process. On some website pages tagged #EnergyTransfer and #DAPL, the organization is already making urgent appeals for funding with this pop up message:

“Climate change” may or may not turn out to be an existential crisis at some point in the distant future. Count us among the skeptical. For the world’s most well-known activist ENGO, the North Dakota jury award is an actual existential crisis, right now. The defendants’ most recent financial reports provide valuable perspective.

The table below includes figures from the most recent annual IRS Form 990 reports for the Greenpeace USA entities and the Annual Financial Report 2023 for Greenpeace International. In the far-right column, we have taken the liberty of apportioning the damages awarded against each entity as estimated above to contemplate how they relate to Greenpeace’s finances. We converted the figures shown for Greenpeace International to U.S. dollars for convenience of comparison.

For non-profits, “net revenue” can be thought of as analogous to pre-tax profits for corporations. It is a measure of revenue left over after operating expenses. Contributions from donors make up nearly 100% of each Greenpeace entity’s revenue.

“Net assets” are the value of all assets net of outstanding liabilities. As such, net assets for Greenpeace would be analogous to a corporation’s equity aka net worth.

The figures in the table demonstrate the seriousness of the financial sword of Damocles the North Dakota jury hunger over Greenpeace’s head on March 19th. Consider the following:

· A $442 million share represents more than 10 times Greenpeace Inc.’s 2023 total revenue, more than 220 times its 2023 net revenue, and almost 100 times more than its 2023 year-end net assets.

· A $125 million share represents more than 5 times Greenpeace Fund Inc.’s 2023 total revenue, more than 3 times its 2023 year-end net assets (in 2023, the entity reported negative net revenue; its expenses exceeded its donations).

· A $100 million share represents more than 83% of Greenpeace International’s 2023 total revenue, more than 20 times its net revenue, and over 130% of its 2023 year-end net assets.

· The total award exceeds the year-end 2023 cash on hand held by all three Greenpeace entities combined by a factor of 7.5, their 2023 net assets by a factor of 5.5, and their 2023 revenue by a factor of over 3.5.

There are other ways to slice the figures, but no way to put a shine on them. Greenpeace has a lot riding on their appeal but that process will not be cheap.

You can get a talented, ambitious online graphic arts designer in India to create your Substack logo for well under $100 (we did; Little Green Guy). But not so much for the U.S. law firms and the attorneys representing Greenpeace in North Dakota. The appeal Greenpeace plans to file will rack up millions of dollars in additional legal expenses.

Greenpeace could win their appeal. The $667 million jury award could be reduced. An angel donor(s) could come to their rescue. Short of those scenarios, the U.S. operations of the world’s most well known environmental non-profit face the very real possibility of bankruptcy.

We close on two notes. First, the North Dakota ruling should cause some introspection and reassessment among ENGOs like Greenpeace. The ruling suggests the need to reexamine their fundraising, training, and in particular support for groups and activities likely to expose them to litigation for something beyond “non-violent direct action.” Jurisdiction will likely become an important consideration where environmental activists might “accidentally” misplace the “N” in NVDA.

Second, for nearly two decades we have quietly watched and wondered if (or when), despite its very real environmental impacts, an industry that has been so central to western civilization’s achievements and living standards would stand up for itself against the relentless attacks of environmental non-profits and ill-informed EcoStatist Charlaticians™. Energy Transfer’s successful litigation in North Dakota is part of an emerging trend of industry firms standing up to aggressive behavior by ENGO’s like Greenpeace and “environmental shareholder activists.”

One would anticipate frequent targets of the most rabid “climate emergency” activists and protests will be emboldened to push back rather than wilt in the face of similar attacks. As Doomberg noted in Finding Out:

Emboldened by this ruling, other industry players will undoubtedly go to the legal mat with full force, as their shareholders will expect nothing less. Companies that remain on the back foot will now have only themselves to blame.

Add to the trend Exxon’s successful pushback against “climate” shareholder activist firm Arjuna Capital, a story we wrote about in Big Evoil Punches Back in February 2024. Just Stop Oil seemed to wise up after one of their key leaders, Roger Hallam, was sentenced to five years in a UK prison in July 2024 for his role organizing protests during which activists climbed on to gantries hanging over the M25 Motorway in London. Last week the EcoStatist group declared it would temper its approach a bit.

What appeared to be limitless global support in the wake of the successful defeat of the Keystone XL Pipeline project in the U.S., the Paris Agreement, and other similar “wins” gave emboldened environmental activists and ENGO’s the idea that they possessed a moral “get out of jail free” card that supersedes laws. Energy Transfer’s victory in North Dakota. Exxon’s running off Arjuna Capital. Local police in the UK jailing a Just Stop Oil leader whose “non-violent direct action” had directly led to the disruption of his fellow citizens one too many times. All are examples this idea was a miscalculation.

Greenpeace supporters will accuse us of Schadenfreude. For this day only, we plead guilty as charged and will accept their judgment.

Greenpeace does not have the same luxury regarding the North Dakota jury’s verdict.

“Like” this post or risk a Strategic Lawsuit Adjuring Schadenfreude Participation from our attorneys.

Leave us a comment. We read them all, respond to most. Refuels our diesel generators.

Subscribe to environMENTAL for free below.

Make someone smile or grimace by sharing this post. Helps us grow. We’re grateful for the effort.

Thanks for an excellent and detailed write-up of this situation. Doomberg's piece was fantastic, but the extra detail here was superb as well. My main concern is that while the organization may be bankrupted, the people there, who will not have to pay anything, will simply form a new organization with the same goals and become equally intrusive. I wonder if they will have learned a lesson from this situation though.

I appreciate your reporting regarding the allegedly nonviolent protests aided and abetted by Greenpeace.