Costly Tradeoffs

The West's obsession with "climate change" and CO2 is costing the world's poor.

“There are no solutions; there are only tradeoffs.” - Thomas Sowell

In late 2015, the United Nations (UN) adopted “Sustainable Development” Goals (UNSDGs). A global framework for addressing some of the most widespread and vexing challenges facing humanity, the plan laid out ambitious goals to be reached by the year 2030.

The 17 UNSDG goals (actually ~31, as some contain goals within goals) have a total of 169 “targets”. These address a wide variety of global human and environmental problems including nutrition, health, poverty, education, equality, energy, sustainable economic growth, and others.

Goal 7 is to “ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern (read: wind/solar/geothermal/hydropower) energy for all”. Goal 13 is to “take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts”. Other environmental-related UNSDG’s target problems like clean water and sanitation, marine conservation, and terrestrial ecosystems.

2023 marked the UNSDG’s halfway point to the target year 2030. A UN progress report last year captures the difficulty in achieving the plan’s ambitious goals (emphasis added):

It’s time to sound the alarm. At the mid-way point on our way to 2030, the SDGs are in deep trouble. A preliminary assessment of the roughly 140 targets with data show only about 12% are on track; close to half though, showing progress, are moderately or severely off track and some 30% have either seen no movement or regressed below the 2015 baseline.

Could the UN have so many goals that it spreads itself too thin for its resources (economic and administrative) and fails to achieve most or all of them in any material way? The 2023 UNSDG Progress Report seems to suggest the answer is yes. As UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres states in the report (emphasis ours):

The lack of SDG progress is universal, but it is abundantly clear that developing countries and the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people are bearing the brunt of our collective failure.

All told, western civilization has spent some $5 trillion – and counting - on the “existential” fight against “climate change”. A question we have asked from our first Substack post (and through gritted teeth for 15 years before) and a common refrain at environMENTAL is: what good could have been done for the world’s poorest with the trillions spent by the advanced nations on “climate change”?

The notion that trillions spent on “climate change” will more directly benefit the world’s poorest than alternative policies addressing more immediate needs, where greater harms can be reduced faster and at far less cost, leads to costly tradeoffs. Some of these more pressing needs are actually key components of the UNSDGs themselves. Paradoxically, some of the UNSDGs work at cross purposes with others.

According to the World Bank, half of the world’s eight billion people live on less than US$6.85/day. Almost 10% (~750 million people) live on less than US$2.15/day - the World Bank’s measure of extreme poverty - with about 60% of that total living in Sub-Saharan Africa. Against this backdrop, prioritizing “climate change” and CO2 emissions is costly in human terms.

What are some examples of the costly tradeoffs impacting the world’s poorest by prioritizing “climate change” above other environmental-related human concerns? What alternative ideas would provide far superior human capital and economic benefits for people at much lower costs? And how are some UNSDGs paradoxically working at cross purposes with others? Let’s take off the green goggles.

We begin with a few examples critical to human wellbeing, all of which happen to correspond to specific UNSDGs.

Drinking Water

One in four people in the world do not have access to safe drinking water. Globally, unsafe water is responsible for 1 million – 1.23 million deaths annually.

In Poor Judgment, we noted the stark differences between electricity generation and distribution in African nations and the advanced world and the impact on development. In some of the nations we highlighted with the lowest electrification and GDP, the rate of death from drinking unsafe water is also tragically high.

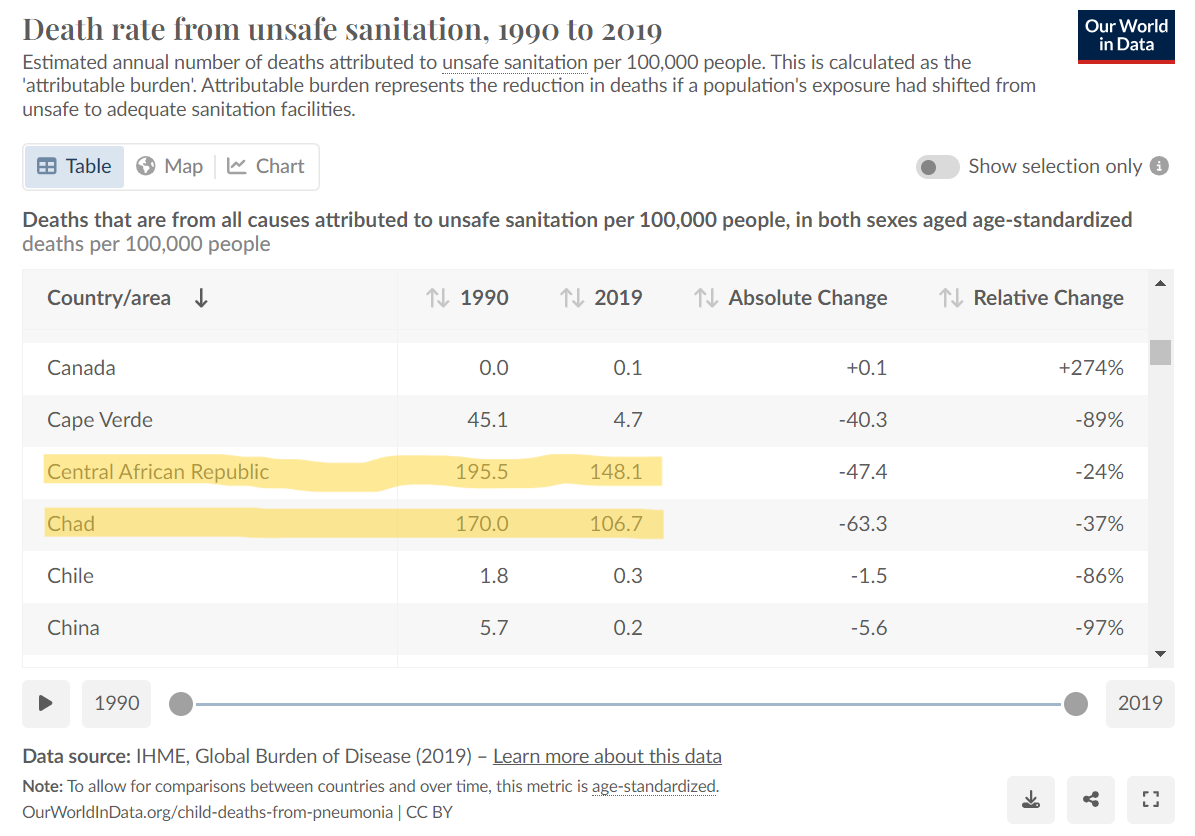

For example, in Central African Republic, where electricity generation capacity is barely 5 watts per capita, the death rate from drinking unsafe water was over 197 per 100,000 in 2019 – about one in every 500 people. In Chad, which we noted has the lowest electricity generation capacity on the continent, the death rate from unsafe drinking water in 141 per 100,000 – about one in every 750 people.

What about South America? Bolivia, which we noted has electricity generation of just over 100 watts per capita, had a 2019 death rate from consumption of unsafe water of 4.5 per 100,000.

How do these figures compare with advanced nations like the U.S., UK, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Canada (the G7) and Australia who, in the aggregate, have spent trillions on “climate change” since 2000? In each, the rate of death from drinking unsafe drinking water is less than 0.1 per 100,000 (and effectively zero in most).

Put another way, citizens of Central African Republic are 2,000 times (in Chad 1400 times, and in Bolivia 45 times) more at risk of death from consuming unsafe drinking water than people in the G7 nations plus Australia. “Climate change” is not killing that many people in these developing countries.

Basic Sanitation

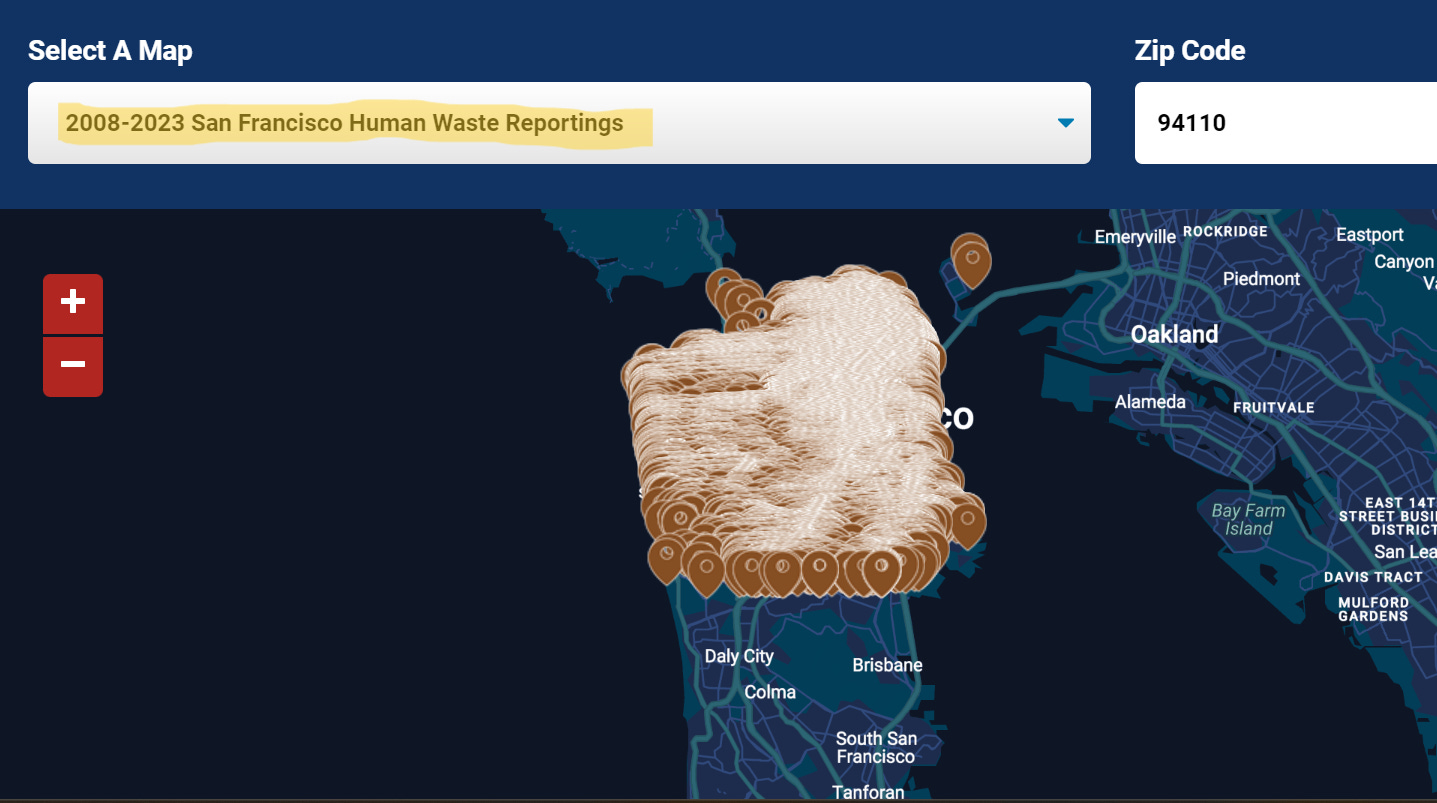

In the high-income countries, 91.2% of the population has access to safely managed sanitation systems and 7.8% to basic sanitation systems. With the noteworthy exception of San Francisco, where city workers can make over $180,000/year in salary and benefits cleaning up human feces, open defecation exists nowhere in high-income countries.

In the least developed countries, 35.3% of the population uses unimproved sanitation facilities and 16.4% still use open defecation.

In the Central African Republic, 70% of the population does not have access to improved sanitation according to 2022 World Health Organization (WHO) data, a percentage which has not changed since 2000. In Chad, the figure was 81.6%, an improvement of 4.3 percentage points since 2000. Nonetheless, death rates from unsafe sanitation in both countries remain among the highest in the world.

Food/Undernourishment

According to 2023 UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) data, even as population increased from ~6.2 billion to ~7.6 billion between 2000 and 2017, the share of world population that was undernourished fell from 12.7% to 7.5%. In raw numbers, this means ~200 million fewer people were undernourished.

But by the end of 2022, the trend had reversed, and the figure had increased to 9.2%. A 1.7 percentage point increase may not sound like a lot, but on a planet of 8 billion people it means 136 million more people became undernourished over just five years. The amount exceeds the aggregate population of three G7 nations (Canada + Australia + Italy). Five years (2017-2022) was all it took to undo about 2/3 of the progress that had been achieved reducing human undernourishment over 17 years from 2000 – 2017.

The highest rates and most troubling continental trends are in Africa. As we have noted in previous posts, the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that disrupted natural gas dramatically effected fertilizer markets, drove prices up dramatically, and led to export restrictions. For western farmers, that meant higher costs and where possible switching to crops requiring less fertilizer. For many small lot farmers across Africa, Southeast Asia and South America, the problem was more severe: would they be able to afford any fertilizer at all.

Indoor Air Pollution

Indoor air pollution is largely a developing world problem that results from cooking indoors using solid fuel sources such as wood, crop waste and dung. WHO proclaims indoor air pollution the largest single environmental health risk, responsible for more than 600 child deaths per day globally. IHME estimates 2.31 million people die prematurely each year due to indoor air pollution. Again using Chad and the Central African Republic as examples, indoor air pollution is responsible 12-14% of deaths. In parts of Southeast Asia and India the figures range from 6% (India) to 12% (Myanmar) to 15% in Laos.

Why do people cook indoors using wood, crop waste and dung? Because they live in energy poverty and do not have access to LPG, propane, natural gas or electricity. Because wood is their preferred fuel, energy poverty leads to deforestation. Villagers in some areas of Africa say that “the trees run are running away from us” as they have to trek further over time to find wood for fuel.

“Environmentalists”, solar cooker advocates, and the UN suggest that solar cookers are a solution to this problem. But one look at the available products suggests this is, at best, only a band aid and not a good one at that.

Worse, it seems a concession to defeat instead of helping them develop domestic fuel supplies, electrification, economic development, and human advancement. Asking Africa, Southeast Asia, and other low-income countries to rely on the sun to cook the food necessary for survival is absurd. Intermittent, weather-dependent ability to cook food to survive is not a solution to undernourishment, poverty, or deforestation.

Clean water, basic sanitation, abundant food, and reducing indoor air pollution require affordable/reliable/on-demand/abundant energy (fuel/electricity), economic development, and infrastructure. American taxpayer subsidies for Chinese solar panels and Scandinavian offshore wind developers have not helped America, or (even worse) the poor in Africa.

Set aside these few environmental examples. There are many problems affecting the world’s poor for which even a fraction of the amounts spent by advanced nations in the name of “fighting climate change” each year could do incredible good. The Copenhagen Consensus’ admirable cost/benefit analysis work is a good example.

Bjorn Lomborg’s 2023 paper Save 4.2 Million Lives and Generate $1.1 Trillion in Economic Benefits for Only $41 Billion puts the shame to the advanced world spending $5 trillion on “climate change” policy since the turn of the century. The paper’s abstract describes the Copenhagen Consensus plan which (emphasis added):

“highlights 12 of the most efficient interventions to speed up progress on the SDGs with Benefit–Cost Ratios (BCRs) above 15. The approaches cover tuberculosis, education, maternal and newborn health, agricultural R&D, malaria, e-procurement, nutrition, land tenure, security, chronic diseases, trade, child immunization, and skilled migration. Spanning 2023–2030, these policy approaches are estimated to cost an annual average of $41 billion (of which $6 billion is non-financial). They will realistically deliver $2.1 trillion in annual benefits, consisting of $1.1 trillion in economic benefits and 4.2 million lives saved.”

Across the world, from the most advanced to the least developed, it is hard to find a case where people receive over $51 in benefits for every dollar spent, while saving 4.2 million lives annually, directly resulting from the western world’s “investments” in “climate change”.

The tens of billions annually for interventions described by the Copenhagen Consensus plan have several distinct advantages compared to the hundreds of billions spent annually by western governments in the name of fighting “climate change”:

They benefit the world’s poorest the most.

They emphasize immediate help to the world’s poorest children.

They return net benefits far in advance of their costs in the short-term (not decades hence, if at all).

They help citizens in the world’s developing nations grow their domestic economies, which history shows is central to emergence from poverty.

They are far less expensive.

Even in the advanced world, the obsession with “climate change” leads to diversion of critical resources away from pressing, imminent and substantial endangerments to human health and the environment. Consider, for example, whether some of the West’s $5 trillion spent only to slightly reduce the growth of carbon-based energy sources might instead turn out to be much more useful today for addressing groundwater contamination from per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

We close by noting that several of the UNSDGs are, paradoxically, working at cross purposes against themselves and the interests of the very groups they intend to help. The UN’s ambitious climate actions (goal 3) combined with its renewable energy efforts (goal 7) - making energy more expensive, and reliable, affordable, distributed electricity more unreachable for those without it - are antithetical to alleviating poverty (goal 1) in the developing world.

Making fuel more expensive in pursuit of “climate action” makes fertilizer more expensive which, in turn, makes food more expensive. It is hard to see how this helps get the UN closer to achieving “zero hunger” in the developing world (goal 2). And so on.

In a superb February 2023 post The Streisand Effect, Substack’s Big Chicken (Doomberg) stated the following:

Last we checked, there are roughly two orders of magnitude more people in the bottom 99% than in the top 1%, and those vast populations will pursue the just and innately human endeavor to improve their quality of life.

Wealthy nations attempting to “solve climate change” confound that innately human endeavor, at home and especially abroad. These are costly tradeoffs. Even the UN Secretary General agrees.

“Like” this post if you’re glad we finally wrote one that’s not 2,800 words long.

Leave us your comments. We read every one and respond to most.

We’re grateful when you share our work as it helps us grow. (Even send it to those who might disagree. We want to hear from more dissenting voices.)

The incompetent fools NEVER think about the downstream impacts of their policies. I can't determine if they are simply evil or just stupid. Probably both.

They're not looking for a pragmatic solution for the world's poorest, they're looking for a final solution to the poor problem.