Poor Judgment

Energy tone-deaf, dumb and blind world leaders and elites prioritize CO2 emissions over human prosperity.

A Christmas Special in The Economist magazine, What Responsibilities Do Individuals Have to Stop Climate Change?, came across our desk in late December. The article opens with a hypothetical proposition:

The vast majority of readers of The Economist would recoil at the idea of stealing from a poor Malian goatherd or a struggling Bangladeshi farmer. Next to none would countenance murdering such a person. They would feel little differently if they committed these crimes as part of a mob, rendering the responsibility diffuse. Nor would they feel much better if their actions were only likely, but not certain, to do blameless strangers serious harm: they would not scatter landmines in a populated area, for instance.

How, then, should we think about readers’ (and your correspondent’s) responsibility for global warming?

This is an easy framing for “journalists” sitting in a heated office in London behind a laptop powered by abundant (if increasingly unaffordable for many in the UK) electricity. We don’t suppose they polled Malian goatherds or Bangladeshi farmers on the question of which they fear more: impacts from climate change tomorrow or energy poverty today. The next paragraph indicates the authors have taken it upon themselves to decide that question for the developing world.

At the extremes, the increasing frequency and intensity of droughts, floods, storms, and heatwaves brought on by global warming is killing people—a tragedy that will get worse as the planet bakes.

This leads The Economist to the heart of the matter. In the process, they inadvertently say the quiet part out loud (emphasis ours):

What volume of emissions, then, may an individual reasonably inflict on the planet? …

Most climate scientists think that by 2070 humans can pump only 1trn tonnes more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere if Earth is to stay below the 2°C target. Divide the trillion by the number of years between now and then and by the number of people on the planet and you end up with a volume of emissions—2 tonnes or so—that an individual can generate each year without pushing the planet towards perdition.

Divide the emissions generated in America each year by the number of Americans, and you get around 15 tonnes per person. Even virtuous Sweden is 3.6. And Americans and Swedes bear some responsibility for China’s 8 tonnes a head, given how many Chinese-made goods they buy. Only poor countries meet the threshold.

The Economist, like the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC), Western Charlaticians, climate activists, and “environmental” non-profits, chooses CO2 emissions as the denominator rather than human prosperity. It assumes every weather catastrophe is caused or exacerbated by human emissions of CO2. Perhaps most troublingly, it assumes weather catastrophes that may or may not occur in the future are a far greater risk to poor countries than energy poverty and lack of economic development today.

Compare UK to Mali in terms of primary energy use and electricity generation capacity. The table below suggests The Economist’s pearl clutching over the impacts climate change may have on the future of Malawian goatherds and Bangladeshi farmers, and the trillions of dollars wealthy nations are spending on “alternative energy”, could be better directed:

How does electricity generation capacity in the global south compare to the world’s top 10 GDP nations? Are wind and solar suited to close generation gaps between the global north and south? And what do recent developments suggest about prioritizing “climate change” at the expense of energy poverty?

We begin by reminding readers of some important facts, inconvenient for western “environmentalists” as they may be:

~80% of global primary energy still comes from fossil fuels.

Electricity generation accounts for ~20% of global primary energy consumption

No examples exist of an advanced nation industrializing without abundant, affordable, reliable, high-quality, on-demand electricity and fuels for transport and process heat.

The policies of the UN and

regressiveprogressive western political leaders, the World Bank, insurers, major banks, and activist scientists have constrained new fossil fuel-based electricity generation capacity in the developing world.No advanced nation ever attempted to add wind or solar power generation without first having an existing fleet of base-load electricity generation powered by fossil fuels (commonly with some nuclear energy) and a robust transmission grid.

The graphic below plots per capita electricity consumption against per capita GDP for the world. We have highlighted the top 10 GDP nations along with some of the poorest nations with the least access to electricity in the global south. The idea that electricity is vital to economic development and human prosperity should not be controversial:

But electricity consumption does not happen without first having generation capacity. Citizens in advanced nations like Canada and the United States would not have high per capita electricity consumption without first having high per capita electricity generation capacity.

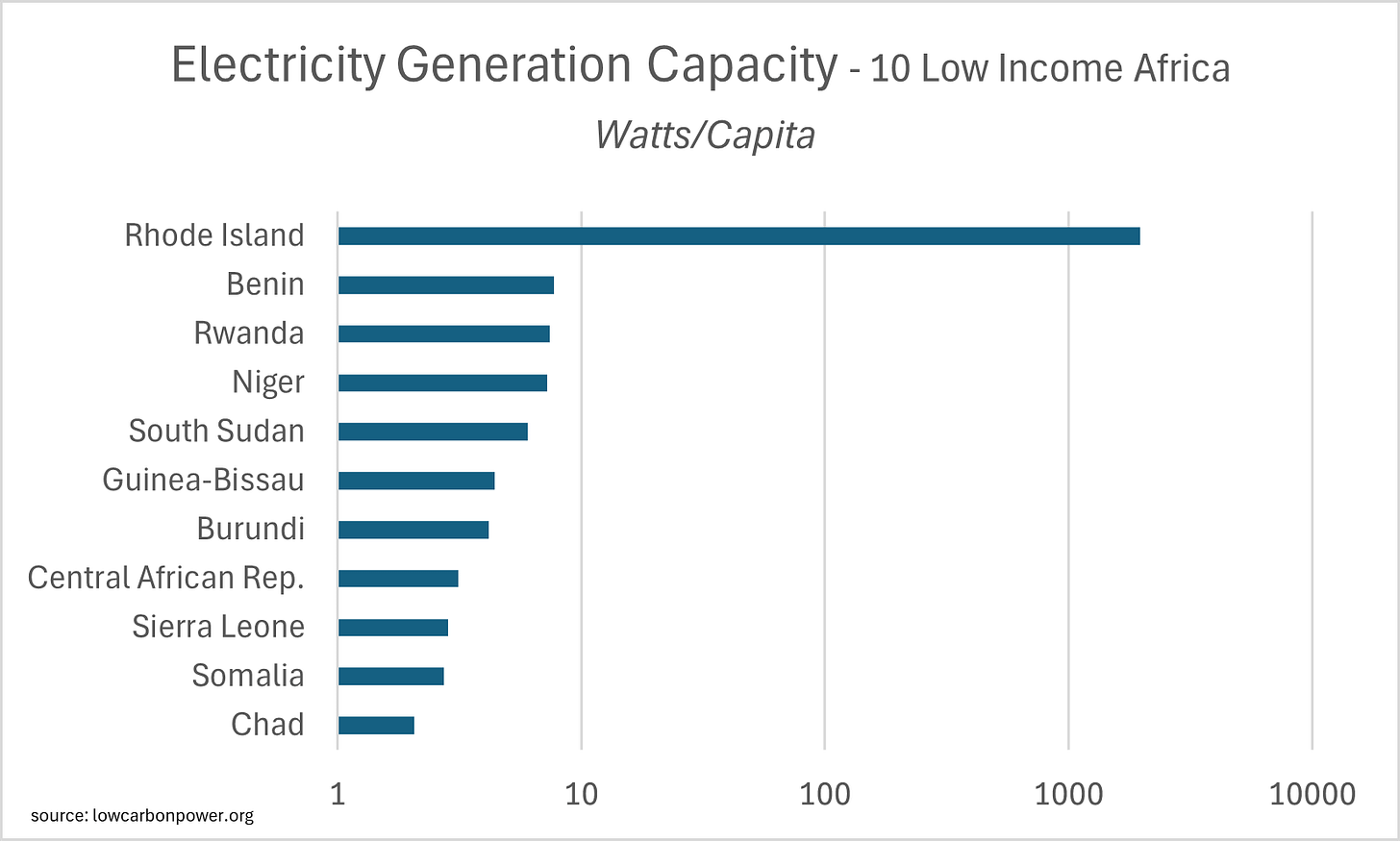

The graph below shows the installed electricity generation capacity of ten African nations whose citizens have the least access to electricity measured by watts per capita. For comparison, we added the U.S. state of Rhode Island. Note the data is presented here using a log scale, without which the bars for the 10 African nations would be invisible.

The figure for Rhode Island is almost 2,000 watts/capita. For reference, Rhode Island, the smallest U.S. state (4,001 square kilometers) has a population of about 1.1 million and installed electricity generation capacity of 2,162 Megawatts (MW). The ten nations in Africa shown have a combined population of ~130 million people served by only 2,655 MW total electricity generation. Chad, home to 17.7 million people and the lowest per capita generation on the continent, has installed capacity of only ~90 MW or just over 2 watts/capita. Rhode Island’s 1,965 watts/capita generation capacity is about three orders of magnitude higher than Chad’s.

In Asia, the 10 countries shown in the graph below are home to 2.4 billion people served by a total of ~641,500 MW installed electricity generation capacity. For perspective, that amount is slightly less than the total capacity of UK + France + Canada + Russia, home to a combined ~318 million people.

Put another way, in Asia, 30% of the world’s population lives off less electricity than the 4% living in the UK, France, Canada and Russia.

What about South America, where installed capacity and GDP per capita are higher than in most of the African and Asian nations shown above? The graph below shows the figures for the seven South American nations with the lowest percentage of population access to electricity:

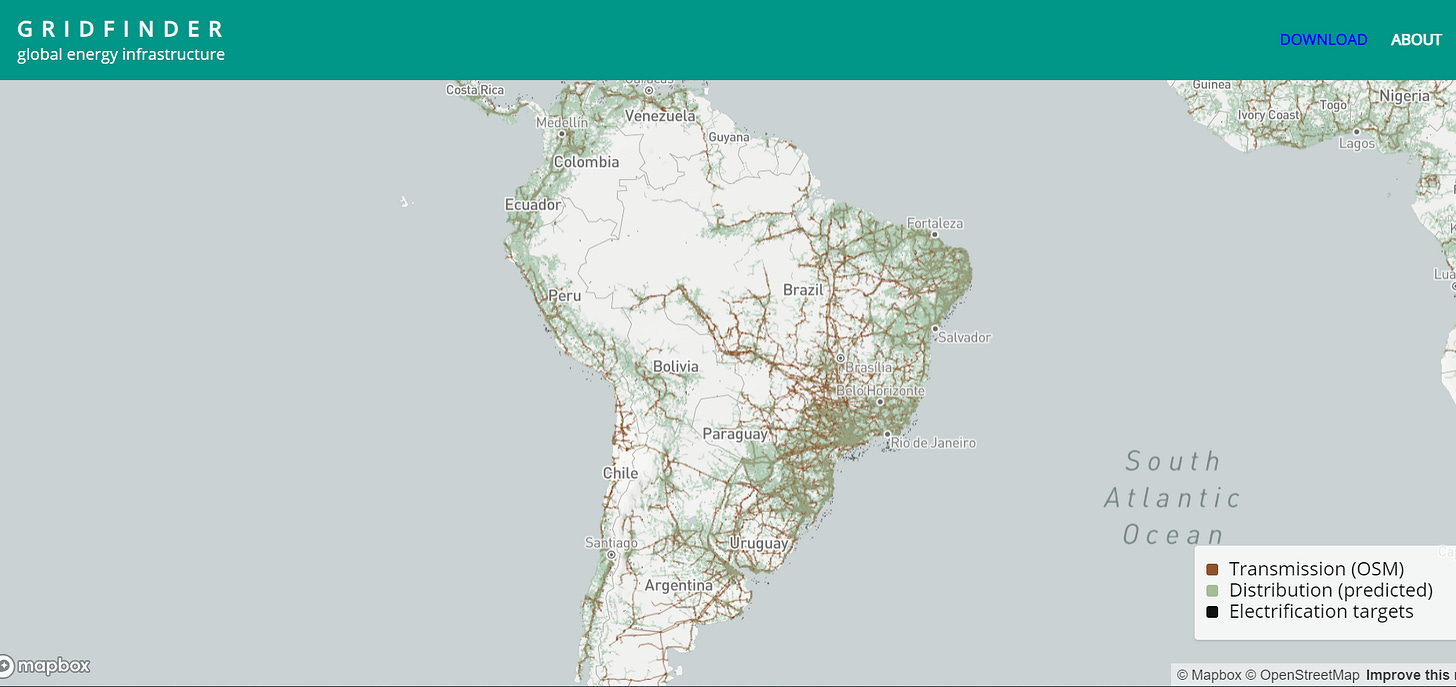

In the seven South American nations shown above, nearly 200 million people spread over 1.2 million square kilometers live off total installed electricity generating capacity similar to Italy. Italy has a population of 59 million and land area covering only 301,000 square kilometers.

The range of installed electricity generation capacity in the 27 nations in the global South in the graphs above is from 2 watts/capita (Chad) to almost 350 (Argentina).

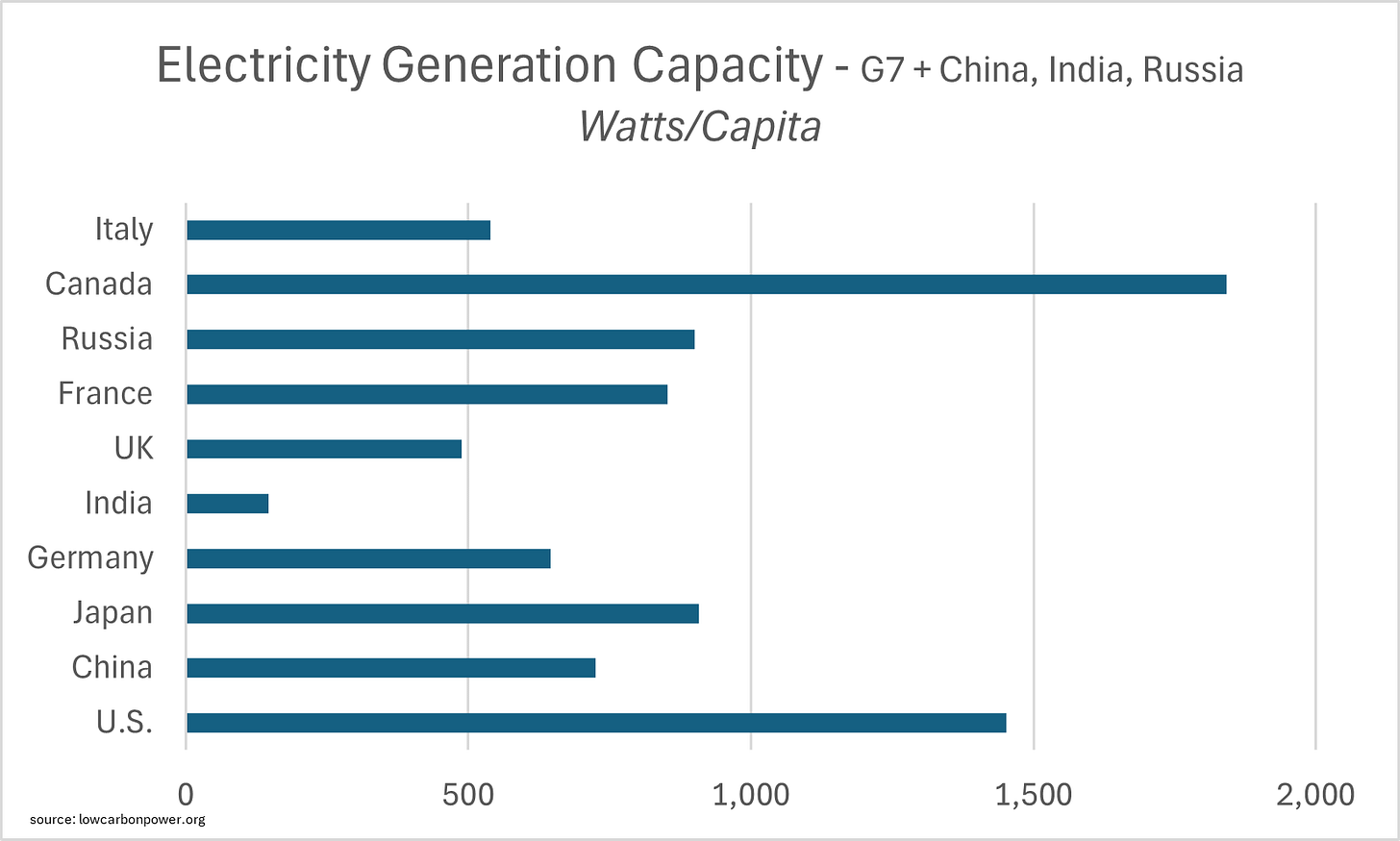

Our last graph shows the same measure among the G7 plus China, India, and Russia. These are the world’s top 10 nation in GDP (US$):

Of the world’s top 10 GDP nations, only India and the UK have installed generation capacity below 500 watts/capita. None of the ten African nations shown in the first graph above have installed capacity of even 10 watts/capita.

“Renewable” energy advocates, climate activists and “environmentalists” will, naturally, suggest that developing countries should “jump over” fossil fuel-based generation as they electrify, touting Lazard’s laughably absurd “Levelized Cost of Energy” (LCOE) as proof wind and solar are the “cheapest forms” of new electricity generation. This is a canard on at least two fronts, both among the many embedded shortcomings of the LCOE.

First, even where developing nations have abundant wind and solar potential, to industrialize, those forms of “renewable” energy are essentially useless without extensive existing base-load generation. As we have shown, existing electricity generation capacity in the 27 countries ranges from nearly non-existent to a fraction of the advanced countries.

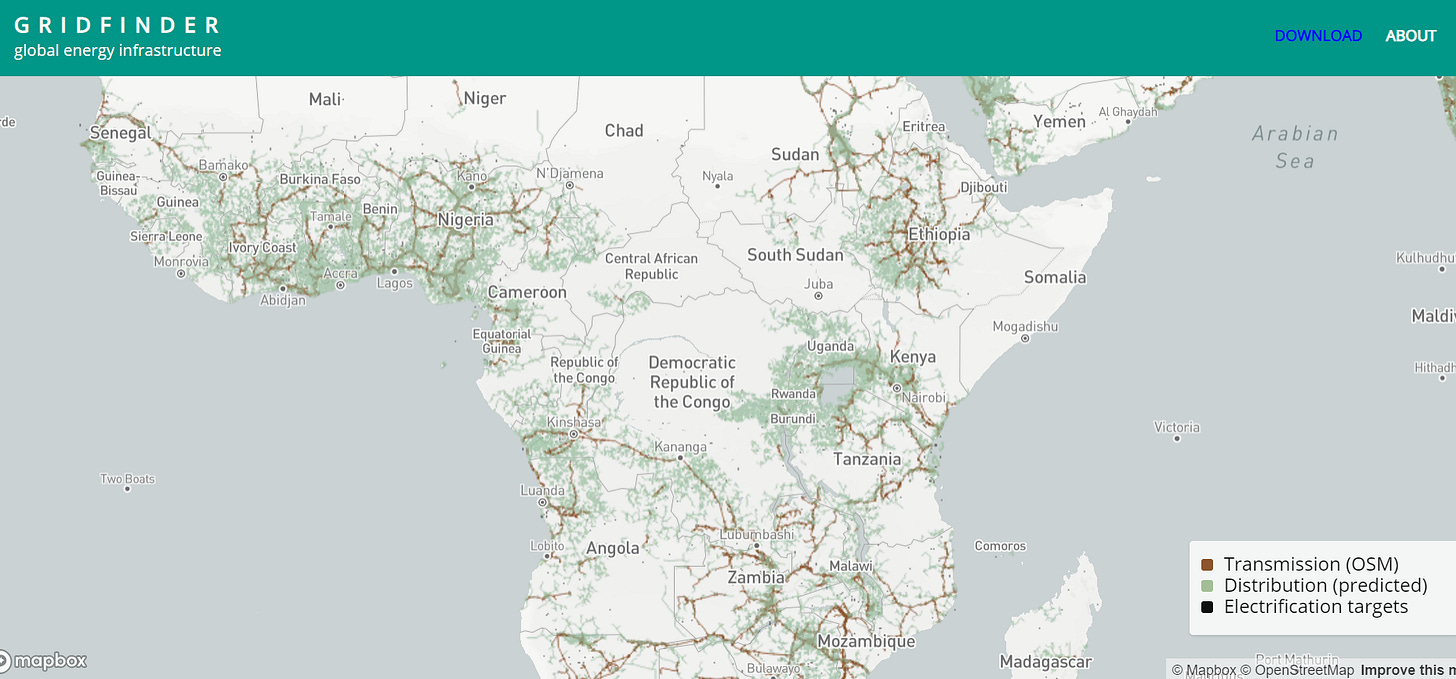

Second, to enable economic development at any scale any new wind and solar installations in these developing countries would be of little value without the ability to connect to the existing transmission and distribution grids quickly and cheaply. But these same 27 countries are among the places with the least developed high voltage and local distribution electricity transmission infrastructure on earth. The images below from gridfinder.com help visualize the dearth of transmission and distribution lines in the global South.

Africa…

Asia…

South America…

We are not the first to say that “energy is life”. We will go one step further: any nation attempting to industrialize to lift its citizens from extreme poverty without affordable, reliable, abundant, on-demand electricity and fuel for transportation and process heat is doomed to fail. And, lost on The Economist, is the fact that advanced nations who constrain those forms of energy are complicit in such failure.

In the absence of the rule of law, property rights, functioning markets and corruption kept in check, no amount of energy is capable of ensuring widespread, equitable prosperity. Energy abundance alone will not solve all or even most of the problems in many of the 27 nations in our analysis. On the other hand, even if all of the other preconditions were met, without affordable, abundant, reliable, on-demand electricity, developing nations would be like race cars without fuel: going nowhere fast.

Encouraging signs of change have emerged over the last two years. After Putin invaded Ukraine, European leaders spent the summer of 2022 scrambling to secure every molecule of hydrocarbons they could wherever they could find them at any price. Among their more pathetically hypocritical attempts was begging African nations for more oil and gas production.

As we noted a year ago in part 3 of Sacrificing Humanity on the Green Altar, after European leaders’ (read: green hypocrites) performance in the summer of 2022, in the weeks prior to COP 27 in Sharm El-Sheik, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni said (emphasis ours):

"We will not accept one rule for them and another rule for us. Europe's failure to meet its climate goals should not be Africa's problem. It is morally bankrupt for Europeans to expect to take Africa's fossil fuels for their own energy production but refuse to countenance African use of those same fuels for theirs."

In December 2022, Vanguard, the world’s second largest asset manager, left the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative. In March 2023, responsible investment fund manager Green Century followed suit.

In May 2023, the Net Zero Insurance Alliance self-destructed at the first suggestions of anti-trust scrutiny. Many of the insurers had committed to restricting or withdrawing their risk capital from fossil fuel energy projects in the lower and middle-income countries, knowing fully well that without insurance those projects would be nearly impossible to finance.

In November 2023, four major banks abandoned participation in the UN’s Science Based Target Initiative scrutinizing corporate climate targets in conjunction with their lending practices. Reuters’ story noting the departure described the fatal blow (emphasis added):

SBTi unveiled plans this year for a new standard that will apply specifically to financial institutions as early as 2024. It will require banks and asset managers not to finance new fossil fuel projects.

This proved too much for Standard Chartered, which wants to continue this business in developing markets. A spokesperson for the bank confirmed it had left the validation process and said SBTi's proposed standard failed to consider adequately "the transition (away from fossil fuels) of our clients and markets".

The final COP 28 agreement emerging from Dubai last month included, for the first time, explicit wording recognizing developing countries’ need to use fossil fuels to lift their citizens from poverty. The final text included the phrase “transitional fuels can play a role in facilitating the energy transition”. This was a grudging acceptance of the need for more electricity generation in the developing world, and the reality that natural gas not only has about half the CO2 emissions as coal. It also has far fewer harmful particulate air pollutants per unit of energy, no small environmental matter in places where people still cook indoors over wood and dung.

Election results and farmer protests from the Netherlands to Germany to Romania demonstrate that the consequences of energy and environmental policies are not lost on working class Europeans. Heating fuel and electricity costs have hammered the working class and poor in the UK. The Green party in Europe is clearly in trouble.

We close by noting it continues to amaze us how overconfident and tone-deaf Charlaticians™, activists and elites are that their “solutions to climate change” are a net benefit for world’s poorest. The Economist’s article is a shining example. The word “poor” appears twice (both places included in this post). The word “poverty” appears once, in the sentence “Global warming is already harming the livelihoods of many people, including lots of poverty-stricken goatherds and farmers”. The possibility that the actual damage and lost opportunity cost imposed on the developing world by their “solutions” today are far worse than the theoretical damages from climate change decades from now is conveniently omitted.

As Doomberg frequently states, “Energy is life!” We would add that without a surplus of energy, living is possible but significant economic development, human advancement and prosperity are not.

Making CO2 emissions reductions the denominator driving energy, environmental and economic policy as opposed to human prosperity has been worse than poor judgment. It is a judgment against the poor, one that renders the value of nature higher than human life and prosperity, and a shameful disgrace that cannot end soon enough.

We recommend Western “leaders” put climate, energy, and human prosperity tradeoffs in proper balance. Otherwise, those who remain energy tone-deaf, dumb, and blind will likely find themselves looking for new work.

Like this post or be sent to install solar panels in Malawi. Or worse, to work at The Economist!

Leave us your comments. They’re part of the energy system that drives this Substack.

Share this post if the idea of hampering economic development in the developing world by constraining energy bothers you.

Writing from South Africa, a country in energy crisis and thus unable to provide continious power to industry, business and homes - I can see the consequences of a downscaled power supply in real time: A reduced quality of life, businesses closing, people being layed off, and so on. In short, economic productivity brutally hobbled. It is a dispiriting experience.

Why rich Western nations would willingly foist such a reality onto their own populations (and others) is scarcely comprehensible.

... and since the industrial revolution, the US population has expanded into the most catastrophe-exposed parts of the country, including the Southeast (FL, LA, and TX account for 2/3 of insured catastrophe losses over time) and the Chaparral of California, which has always been prone to long periods of drought and wildfire.

In 1900, the population of Los Angeles -- which was a desert -- was less than 1 million people. Mulholland brought water to the area from the Owens Valley and now LA is a lush, green desert. And they wonder why there is wildfire risk. It has very little to do with climate.