The Green Cold War - Part 2

One side failed to understand the consequences of its policies. The other side understood, and capitalized.

“If one has made a mistake, and fails to correct it, one has made a bigger mistake.” - Plato

The West’s ill-conceived environmental and energy policies inadvertently gave Russia and China significant geopolitical and economic advantages. This put both countries in a strong position to use energy and other critical commodities as economic weapons to weaken the West.

Policy changes in the U.S, Europe and other advanced nations prove circumstances on the ground have finally caused “leaders” in the West to begin to recognize the peril caused by environmental and energy policies denominated entirely by CO2 emissions and climate change. Hard lessons learned about the criticality of energy security caused the West to start to reverse course. This manifest in everything from Germans building floating liquified natural gas (LNG) terminals and burning more lignite (coal) in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, to legislative efforts in Europe and America to increase domestic and “friendsourcing” of wind and solar production as well as lithium-ion battery supply chains.

“Energy security” went from a forgotten 1980 term to center stage in the West in one year. The situation became serious enough that even regressive “progressive” Western political parties began to embrace the dreaded “N” word (nuclear).

But the West’s attempts to rectify the consequences of almost two decades of interrelated environmental, energy and economic policy mistakes will be politically difficult and expensive. Building more resilient, friendly, and domestic supply chains, especially for the new nuclear power plants that will be key to emissions reduction from electricity generation, will not be accomplished quickly or easily.

European and U.S. attempts to use legislative and trade measures to “reshore” or “friendshore” wind and solar manufacturing, for example, will not be without consequences, including friction between the allies themselves. Aggressive tax and subsidy measures in the 2022 U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) angered the European Union. In early 2024, they countered with their own “Net Zero Industry Act” with a goal of manufacturing 40% of the EU’s net zero technologies on the continent by 2030. Russia and China can be expected to counter Western protectionism by ratcheting up their use of critical resources as weapons in The Green Cold War (TGCW), including export “licenses” (a form of government resource control), taxes or tariffs, or outright bans.

In addition to China’s near stranglehold on low-cost wind and solar hardware, the West’s obsession with “alternative energy” and “electrify everything” turns out to have given China another critical supply chain advantage: production and processing of critical minerals. Whether neodymium iron boron magnets for wind turbines, or lithium, graphite or other critical minerals for EV batteries, China’s market position in certain key commodities and/or processing steps is even higher on a percentage basis than its market position in solar panels and wind turbines.

China produces ~60% of the world’s rare earth elements (REE) and processes ~90% of global production. It produces about two thirds of the world’s graphite, and processes ~90% destined for electric vehicle batteries. This graphic from Visual Capitalist provides a glimpse of China’s dominance:

China built the world’s low-cost wind and solar hardware industries on the back of Western “alternative energy” subsidies and the artificial demand they created. China also controls the processing of “clean energy” metals required by the “energy transition” we have mandated.

Western mine permitting processes and environmental regulations combined with relentless activist opposition make it nearly impossible to open most new mines in the U.S. and Europe. The few that are permitted commonly take about a decade to reach full production. Because they are subject to largely reasonable and necessary environmental regulation compared to China, it is hard to conceive that new U.S. or European mines would be cost competitive even if they could be opened.

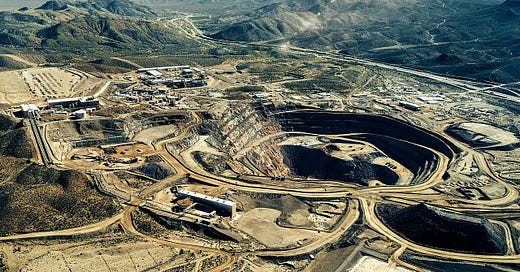

In the last few years, the U.S. recognized and finally acted on its vulnerability to China’s REE supply chain stranglehold. The Mountain Pass mine in California’s Mojave Desert produces ~15% of the REE’s consumed globally. In 2023, Mountain Pass recommissioned its integrated processing facility. Because advanced defense systems rely on a variety of REEs, U.S. legislators authorized funding for Mountain Pass under the Defense Production Act (DPA).

Russia has a similar geopolitical energy leverage point in this story: the nuclear fuel cycle for nuclear power plants. A shift is taking place in Western nations toward nuclear power as an obvious emissions-free replacement for coal and natural gas, and a far superior source of reliable, high-quality electricity generation versus wind and solar. But after four decades of eschewing new nuclear power, the West has an enormous hill to climb to recover.

Russia sits in the driver’s seat. According to the World Nuclear Association:

Russia produces ~5% of the world’s mined uranium. Its neighbor (a traditional ally and former Soviet satellite) Kazakhstan produces ~45%. 50% of world uranium production is controlled by Russia and Kazakhstan.

Presently (with the exception of Canada’s unique CANDU reactors), the world’s entire nuclear power plant fleet relies on only four commercial “conversion” plants for the initial processing of mined uranium, the necessary step before it is sent to enrichment plants for processing into nuclear fuel rod assemblies. Plants in Russia and China account for ~50% of the ~55,000 metric tons annual nameplate capacity, but ~63% of actual annual production. (A U.S. plant with capacity of ~7,000 annual tons is being refurbished for restart.)

Russia (46%) and China (11%) control 57% of world uranium enrichment capacity and processing into commercial nuclear power plant fuel assemblies. China is expected to increase capacity substantially.

About 20% of the EU’s natural uranium and 26% of its enrichment services are purchased from Russia. For the U.S., those figures are about 14% and 28%, respectively.

In our definition of TGCW, we noted it is a “a (mostly) non-kinetic battle of superpowers” and is being fought on three interdependent fronts, environmental, energy and economic. In addition to the energy-related economic advantages we have noted, in the TGCW we would anticipate Russia and China to press others.

Russia and China account for about 25% of the world’s exports of nitrogenous fertilizers and China controls 24% of the world’s phosphatic fertilizer exports. Russia and Belarus combined produce 32% of the world’s potassic fertilizer exports, and China alone imports 10% of the global total. Russia and Ukraine combined are responsible for 15% of the world’s cereal grain exports.

Consider a few key events of the last several years in the broader context of TGCW.

In September 2021, Russia completed work on the Nordsteam 2 pipeline. In February 2022, Germany halted the project’s approval after Russia formally recognized two breakaway regions in eastern Ukraine. Two days later, Russia invaded Ukraine.

Over the next several months, Russia restricted gas flows through Nordstream 1 for all manner of reasons, even blaming western corporations for some. At a media conference at EU headquarters in Brussels in July of 2022, one week after Russia shut down the Nordstream 1 pipeline for “annual maintenance”, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, stated (emphasis ours):

“Russia is blackmailing us. Russia is using energy as a weapon, and therefore, in any event, whether it’s a partial, major cut-off of Russian gas or a total cut-off of Russian gas, Europe needs to be ready.

Two months later, the Nordstream 1 pipeline was sabotaged. We find it hard to make the case that the act was not related to Germany’s and Europe’s dependence on Russian natural gas, which was a direct result of German and European environmental and energy policies.

Trade sanctions between Russia and Europe involving fertilizer began before the Ukraine war. After Russia’s invasion, the EU imposed sanctions on individual oligarchs who owned fertilizer industries and on Russian potash. In a matter of months, with concerns growing about global food insecurity, by December the EU eased its sanctions by allowing individual EU member states to unfreeze the assets of those oligarchs to support the production of food and fertilizer. Meanwhile, Russia set quotas on the export of fertilizers until May 2023, ostensibly to maintain sufficient supplies for its own farmers. Part of the way Russia has responded to European and U.S. sanctions is by restricting or banning some agricultural commodity exports and imposing taxes on several others.

China announced export bans on phosphate rock and imposed “export licensing” of fertilizers in September 2021, five months before Russia invade Ukraine.

In October 2023, China began requiring graphite export “permits”, and by December 2023 ratcheted those up to government “approval” for all graphite exports. In January, Bloomberg reported the controls led to a 91% drop in graphite exports from November to December. In December, China also banned the export of rare earth extraction and separation technologies.

Using food, fertilizer, critical minerals, energy, and energy infrastructure as economic weapons has serious implications, not least for the world’s poorest. All increases in food and energy costs hurt the world’s poor the most. They are the biggest losers in TGCW.

Russia’s war in Ukraine finally caused many Western leaders, particularly those in Europe, to wake up to exactly what and on whom their “energy transition” was relying. In the same manner advanced nations clearly failed to think through the economics and physics of their “energy transition”, they failed to consider the resource requirements and necessary supply chains as well.

The convergence of all these environmental, energy and economic dynamics is likely to have profound domestic political consequences in Europe, America, the UK, and Canada. Some of these consequences are already evident in parts of Germany, the Netherlands, and elsewhere in Europe.

We close by noting a remarkable irony. The net effect of TGCW, and the preconditions set for it by the advanced western nations’ infatuation with “alternative energy” and panic over climate change, is that the world is now awash in hydrocarbons as a direct result.

Finally faced with the first-order consequences of its ill-fated “energy transition,” Europe scrambled to secure LNG supply from the U.S. and Middle East, and Germany burned lignite coal to fill the necessary gaps for electricity generation, a situation only made worse after shutting its last fully functional nuclear plants in April 2023. The second order consequences of Germany’s Energiewende include a rapid deindustrialization that is still unfolding.

But globally, oil and natural gas production soared. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicted in its February Oil Market Report that “world oil supply is set to increase by 1.7 million barrels/day (mb/d) to a record 103.8 mb/d in 2024, with non-OPEC+ providing 95% of the incremental barrels. Most of that non-OPEC+ increase came from just four U.S. counties located in the Permian Basin (two in west Texas and two in southeastern New Mexico).

American energy firms responded to the situation and the market signals by cranking up not only domestic crude oil production to record levels….

...but natural gas as well.

China and Russia did not conspire to start TCGW. Western nations did it to themselves.

Nobody forced European countries to outduel each other in a race to net zero that none will achieve by the dates promised. Twenty plus years of subsidizing wind and solar in the U.S. has resulted in an increasingly fragile electric grid (as Substack author Robert Bryce details in the recent docuseries Juice). This would be dangerous enough even had electricity costs for end users become cheaper, as Charlaticians™ promised would result from massive subsidies to wind and solar energy.

Instead, the opposite happened. This is particularly evident when comparing states like California, with high penetration of wind and solar energy on the grid, to states like Georgia which has close to none of either, against the national average. The fact that it may have been driven by well-intentioned attempts to save the world from “the existential climate change crisis” does not change the outcome.

In the U.S. and Europe, The Green Cold War often appears on the surface as loosely connected chains of absurdities that defy economic reason over many years. U.S taxpayers loan $528 million to bankrupt solar companies like Solyndra. On the very same day natural gas in California trades at more than ten times the price in west Texas. Power plants in Massachusetts burn diesel imported from Russia.

What connects all of them is a creeping rot weakening western economies from within. Strong economies rely on affordable, reliable, durable, high-quality energy systems. Policies that degrade these conditions weaken the nations that mandate them.

The twentieth century Cold War was a nuclear arms race that weakened the Soviet Union and sped its economic collapse, without the Soviets helping America by purchasing its weapons. In The Green Cold War, the West chose to weaken itself economically by subsidizing China’s industrial buildout to produce solar panels and wind turbines we then bought. Additionally, Europe and particularly Germany made themselves more reliant on Russian natural gas for industry and to provide base-load electricity in support of its growing wind and solar generation. As if these were not bad enough, the West did not consider that it was relying on a global supply chain in which many of the critical mineral resources necessary to achieve its net zero ambitions were also largely controlled by China.

We will not be surprised to see China and Russia press these advantages in attempts to weaken the U.S. and Europe economically. Nor will we be surprised to see this occur with varying degrees of coordination, whether explicit or otherwise.

The war in Ukraine shows that we live in dangerous times. Western nations weakening their own economies while strengthening those of their adversaries do so at significant risk.

As a powerhouse of energy, food, and other key commodity production, America is positioned well to emerge from TGCW with the least damage. Germany’s predicament is a lesson to the rest of the world’s advanced nations. We hope they are willing to learn.

“Like” this post or we’ll send you to Washington, DC to teach a remedial class for Congress.

Leave us a comment. They are part of our energy supply and landmarks that help us navigate.

Please share our work. It helps us grow. We’re grateful for your support.

Excellent article. The graph of Californias energy cost is shocking. At .30 per hour no one can afford to turn the lights on much less charge all the electric vehicles they are mandating. Complete ban of the combustion engine by 2036? The results will be devastating. The commercial railroads will somehow convert to all electric to serve our west coast ports? Not going to happen.

Given that the province of Saskatchewan is the world's largest producer of potash, and the second largest producer of uranium behind Kazakhstan, and hosts 40% of Canada's farmland, do you think the province is well-positioned to weather TGCW? Great essay.