Risky Business

"Socialistas" made an environmental mess in Venezuela. Western energy companies could help, but recent history nearby counsels caution.

“Greedy and predatory capitalism is the cause of all environmental problems.” - Nicolas Maduro

The Ministerio del Poder Popular para el Ecosocialismo (Ministry of Popular Power for Ecosocialism, or “Ministry of EcoSocialism” as it is known) is the Venezuelan federal government’s counterpart to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The first tab found on its website is titled “EcoSocialism, ” and the page begins as follows (emphasis ours):

The planetary ecological crisis continues its accelerating deepening while further endangering the balance of life and the survival of the human species. The climate crisis, the systemic crisis, is the total crisis of the capitalist model, since it is based on a logic that is inherently expansive and predatory towards nature, resources, and people. This manifests itself in a way of life that makes the means of subsistence for some the means of death for others.

Given the circumstances in Venezuela, only a government with “huevos grandes,” cognitive dissonance, and a projection problem of the highest order could post such an inversion of reality. The page ends with the obvious answer to these crises:

Ecosocialism is poetry, it is song, it is future, it is hope, it is the tender gaze of a child knowing that they will have a planet where they can develop as a species, Ecosocialism above all things, is life, it is spirituality, it is peace.

Back in the real world, what has actually been predatory towards nature, resources and people in Venezuela is not “the capitalist model.” EcoSocialism has been a tragedy for its subjects, and like every Statist regime before it since the era of industrialization, a disaster for the country’s environment.

Last summer, Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro posted this video on Facebook to “reaffirm our commitment to its protection and preservation” the month before introducing his Gran Misión Madre Tierra, or “Great Mother Earth Mission,” to address Venezuela’s “most pressing” crisis: it’s climate emergency(!). The “most relevant” comment made us laugh, but the sad irony of the reality made us want to cry:

The human and environmental wreckage left by a quarter century of Hugo Chavez’ and Nicolas Maduro’s Socialista regimes ended on January 3rd. That morning, President Trump used the U.S. Army’s elite Delta Force to remove Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores from Venezuela under cover of darkness, hauling him to New York to face charges of narco-terrorism, drug trafficking conspiracy, and weapons offenses.

The Trump administration appointed Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodriguez as interim President. It took control of Venezuela’s oil production.

Six days later, Trump hauled about a dozen executives from major U.S. and European energy companies to the White House to attempt to “encourage” them to invest more than $100 billion to expand Venezuelan oil and natural gas production. The reactions he received from U.S. energy firms Exxon, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Halliburton, Valero, Marathon and others, and European giants Shell, Repsol and Eni varied.

Chevron is the only American oil major still operating in Venezuela, under license granted by previous U.S. administrations. Chevron CEO Mike Wirth indicated the company could feasibly increase production through existing joint ventures but was hesitant to commit to major new investments.

Exxon CEO Darren Woods called Venezuela “uninvestable.” Trump responded in his usual direct manner:

“I didn’t like Exxon’s response. You know we have so many that want it. I’d probably be inclined to keep Exxon out.”

When ConocoPhillips CEO Ryan Lance the President that his company was Venezuela’s largest non-government creditor, Trump responded by saying that ConocoPhillips would be able to recover a lot of its money but “we’re going to start with an even plate … we’re not going to look at what people lost in the past because that was their fault.” When asked how much money the company had left behind in Venezuela, and Lance informed him the figure was $12 billion, Trump laughed it off with a smile and responded, “good writeoff.”

For all that has been written in the legacy media about the very real political, legal, financial, and other risks that Woods and other industry executives expressed at that January 9th White House meeting with Trump, little has been said about another exposure to risk that awaits western energy majors who venture into (or back into) Venezuela. But the risk of entanglement in costly environmental liability litigation is very real given conditions on the ground there, and precedents already set in a nearby South American country increase it.

How bad is the environmental mess left behind by Maduro and the Socialistas in Venezuela? How did the situation get so dire? And how might a costly, hard-learned lesson suffered by the only U.S. oil major still operating there factor into other western energy majors’ decisions about investing in Venezuela?

We begin with the extent of the environmental damage rendered by a quarter century of Socialist rule relying almost entirely on oil revenues. The question is difficult to answer.

Nearly 100 years of oil production, most of it without any meaningful environmental regulation, has surely had negative impacts, but no one knows the full extent of the toll on Venezuela’s soil, surface waters, groundwater, sediments, or ecosystems. What we do know is that the situation was made dramatically worse by the steadily deteriorating operational conditions of its oil infrastructure, lack of capital investment to repair it, and how Venezuela’s state-owned petroleum company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A, (PDVSA) was run in the years after Hugo Chavez took office in February 1999.

Oil and gas industry experts have offered many broad estimates that put the cost of restoring Venezuelan oil production to its historical peak of ~3.5 million barrels per day (mmbpd) at well over $100 billion. But no published, robust estimates exist for the aggregate cost to remediate the soil, surface water, groundwater, sediments, or sensitive ecosystems impacted by current and historical oil and gas production, conveyance and storage facilities to standards protective of human health and the environment.

No projects humans could perform for any price could fully restore certain ecosystem losses, such as those to the extensive mangroves, brackish marsh, and benthic communities damaged. Time and nature will have to heal the damage once the sources of the contamination are abated.

We know the situation took a dramatic turn for the worse after about 2010, and that it did not have to be this way. In the period before Chavez, PDVSA was regarded as the leader in environmental health and safety of Latin American oil production, with practices closer to American and European norms than others in South America. How did the condition of Venezuela’s environment become so dire?

When Hugo Chavez took office in February of 1999, PDVSA’s oil production was 3 – 3.5 mmbpd. By 2002, deep polarization over his socialist reforms, not the least of which included attempts to gain greater control over PDVSA, ostensibly for the purpose of redistributing more of Venezuela’s oil wealth to the marginalized, resulted in a coup that temporarily ousted Chavez.

Following the coup, thousands of workers went on strike and demanded new general elections. Many PDVSA workers were among them, and the strike reduced the company’s oil production to ~50,000 bpd. Chavez responded by firing around 18,000 PDVSA workers, nearly half the workforce, replacing them mostly with regime loyalists and retirees who were not the experienced labor and management that knew the oil infrastructure and how to operate it, maintain it, and repair it.

The consequences were grave. After 2003, PDVSA would never return to its 3.5mmbpd peak production. Things got even worse four years later.

Production and operations took another hit in 2007 when Chavez expropriated foreign energy company assets. Many of the companies, including ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips, had been brought in to increase production of hard-to-process heavy crude in Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt.

The expropriation led oil industry talent and foreign capital to flee Venezuela, leaving PDVSA unable to fully capitalize on the resource or to manage it most efficiently, not the least of which included reducing spills and environmental risk. Without foreign investment, PDVSA was left in a nearly impossible position: unable to invest to update its dilapidated and corroded pipelines, leaking storage tanks, and hazardous equipment, Venezuela was literally spilling its financial lifeblood as a contaminant into the very ecosystems on which its citizens rely to survive. The combination of PDVSA’s workforce, stripped of its best technical and managerial expertise, and lack of foreign investment, corruption and kleptocracy left the Venezuelan oil industry in a constant battle against decaying infrastructure and the country’s environment a wreck.

Despite all of that, PDVSA was still producing about 2.5 mmbpd when Chavez died in 2013. While down nearly 1 mmbpd from Venezuela’s historical peak, oil prices remaining above $80/barrel since 2010 kept the Socialist regime Maduro inherited afloat despite deteriorating conditions for citizens.

That changed when global oil prices collapsed in late 2014 and throughout 2015. Government revenues plunged, the conditions of the country’s oil infrastructure deteriorated even further, and the number of spills and damage to the environment increased.

Three years after taking office, the Maduro regime simply tried to make the oil spills, pipeline and storage tank leaks, and other environmental impacts that are readily visible to citizens – and even to the world’s satellites – go away. In 2016, PDVSA simply stopped publishing operational data that included this information.

After 2016, with government income dramatically reduced from persistent oil prices below $65/barrel, the human and environmental crises in Venezuela deepened rapidly. In scenes sadly symbolic of the logical ends of the depraved philosophy of EcoSocialism, conservation website Mongabay and others reported that starving animals in zoos attacked each other, and citizens began hunting wild animals in national parks and breaking into the nation’s zoos at night to feed themselves:

In August 2017, a keeper at Zulia Zoo near Maracaibo reported that animals had attacked each other for lack of food. Other animals were apparently slaughtered by the keepers to feed the facility’s carnivores. Thefts have been rife at the same zoo. Forty animals have been reported stolen, likely to be killed and eaten. Vietnamese pigs, monkeys, macaws, and redfish were taken at night. Some robberies involved endangered species including tapirs. Two peccaries, a type of wild pig, were stolen, while buffalo were butchered on site.

Similar stories have been reported from other Venezuelan zoos: Peacocks and other captive birds were the victims of hungry thieves who raided Bararida Zoo in Barquisimeto, 250 kilometers (155 miles) southwest of Caracas. Several men dismembered a horse inside the Caricuao Zoo in Caracas, the capital; tapirs, sheep and rabbits have also been stolen from there.

Widespread damage from Venezuela’s oil industry is perhaps most evident in Zulia and Falcon states, the historical center of the country’s production, separated by South America’s largest lake. Lake Maracaibo, a freshwater lake when filled thousands of years ago, is now an estuarine brackish lake connected to the Gulf of Venezuela and the Caribbean Sea beyond by a narrow straight. A historical estuary that served as a breeding ground for fish, shrimp, and other marine life, teeming with manatees and a wide variety of birds and other wildlife, today its waters and shores are fouled with oil.

Commercial oil deposits were discovered in the lake in the 1920s and soon thereafter rudimentary offshore drilling on pilings began, with major commercial offshore expansions increasing rapidly from the 1940s – 1960s. Modern descriptions of the field estimate that there are ~25,000 kilometers (~15,000 miles) of pipe under the lake.

Many of the pipes were placed 50-70 years ago, but some are likely nearly a century old. The lake displays the evidence of the age and condition of the infrastructure. A 2021 article from NASA’s Earth Observatory showed satellite images of Lake Maracaibo swirling with oil slicks, noting:

“According to reports from news agencies, environmental groups, and human rights advocates, as many as 40,000 to 50,000 oil leaks and spills occurred between 2010 and 2016 across Venezuela, including Lake Maracaibo.”

Spills and releases at refineries along the Venezuelan coast east of Lake Maracaibo have increased dramatically since 2016. Around 2007, further south bordering country’s northern Amazon, production began increasing in the Orinoco Belt, home to 300 billion barrels in proven oil reserves in the Orinoco river basin. The Belt’s four blocks on the north shore of the river are shown on the overlay map below.

Exploitation of another natural resource in the Orinoco river basin with significant environmental impacts has also increased rapidly since 2016. As with the oil, the impacts are dramatically worse because they are not extracted and processed in a manner consistent with western environmental regulatory standards. The areas are remote, lacking environmental oversight and enforcement. And, like the Orinoco basin’s oil, Maduro has also used these resources to keep his “Ecosocialist” regime afloat, at the expense of both the Venezuelan populace and its environment.

In 2016, with oil prices effectively half of what they had been three years earlier, and Venezuela’s human tragedy, government finances, and corroding oil field infrastructure all deteriorating with increasing velocity, Maduro needed additional sources of revenue. That year, he established the Orinoco Mining Arc, a giant swath of land comprising ~12% of Venezuela’s south – an area roughly the size of Portugal.

The Arc contains significant deposits of diamonds, coltan, uranium, nickel, titanium, and some rare earth metals. And gold. The Mining Arc’s four major blocks are directly across from the Belt’s oil production areas on the south side of the Orinoco River, shown in the overlay map below.

Increasingly starved of oil revenue, after fouling Lake Maracaibo and Venezuela’s western coast for 15 years with dilapidated and corroding oil infrastructure the Socialist regime could not properly maintain, upgrade or replace after sucking off Venezuela’s oil revenues for personal and party gain, Maduro turned to oil extraction and mining in the country’s remote Orinoco River basin to try to remain in power. This spread the environmental destruction EcoSocialism wrought in Venezuela’s north to the country’s south and east, adding one of humanity’s most environmentally-destructive industries (mining) for good measure.

Last August, Washington, DC-based Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency (FACT) Coalition estimated 86-91% of the gold mined in the Arc is produced illegally, generating ~$2.2 billion annually for the Maduro regime, noting (emphasis added):

While ostensibly designed to attract foreign investment, the Arc instead enabled rampant illegal extraction, controlled by military elites, Colombian guerrillas, and mega gangs like the Tren de Aragua…

The environmental devastation from these activities is catastrophic: over 1,000 square miles of the Amazon have been deforested, and 90 percent of freshwater sources are contaminated by mercury. Unlike Colombia and Peru, where non-state armed actors dominate, Venezuela’s gold economy is orchestrated by a symbiotic network of political elites, military officials, and transnational criminals, rendering it both a humanitarian crisis and a geopolitical tool for evading sanctions.

In 2019 the U.S. banned exports of the diluents needed to blend with the heavy crude from growing production in the Orinoco Belt in order to make it flow through pipelines and load on ships. America has a surfeit of these light oils, condensates, and natural gas liquids (NGLs) from the fracking boom, with NGLs alone making up ~1/3 of America’s 20+ mmbpd, world-leading production of total petroleum liquids.

Desperate for funds and diluent to stay in power, Maduro did what failing Collectivists always do – turn to other Collectivist, authoritarian, and even despotic Islamic theocratic regimes for help. Iran became a key supplier of diluent. Russia provided more oilfield equipment, expertise, investments, finance and oil trading, collateralizing billions in loans to PDVSA with stakes in future oil deliveries and upstream joint ventures. China rolled and extended oil-collateralized loans to Venezuela (distressed debt in resource-rich foreign countries being its preferred means of non-kinetic resource imperialism), while also “investing” in oil production joint ventures with PDVSA. China became Venezuela’s largest oil export customer, much of it through “shadow fleets” and ship-to-ship transfers.

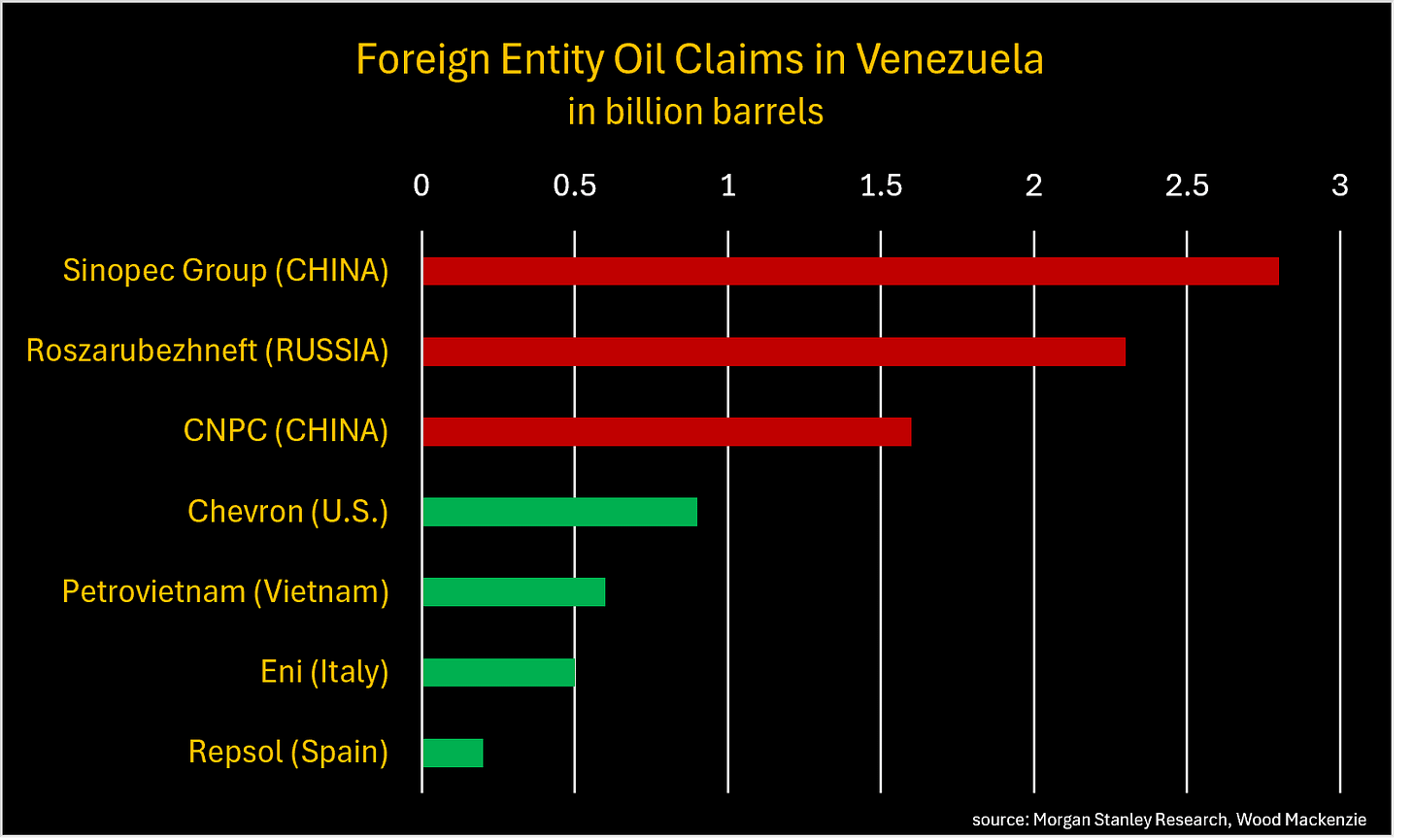

Since Venezuelan law prohibits foreign firms from owning Venezuelan oil reserves directly, they invest in joint ventures with PDVSA. Through these means, Chinese and Russian firms hold claims worth billions on Venezuelan oil.

By the time Maduro was forcefully extracted earlier this month, Venezuela’s foreign debt had ballooned to nearly $200 billion. China was the Maduro regime’s largest oil buyer in 2025 with an estimated 450,000 bpd, but an untold amount of Venezuelan oil has been sent to China as “in-kind” debt repayment over the last decade.

It should be obvious that Chinese, Russian and Iranian foreign interests operating in Venezuela do not conduct oil production and hard rock mining with the same level of environmental scrutiny and regulation to which western energy and mining firms are held. The fact that oil production and mining activity in the Orinoco Belt and Arc are in remote areas where state and federal environmental regulators (such as they exist) are few and far between, people are starving, and corruption is rampant only adds to the likelihood that, left to their own devices, PDVSA and its Chinese, Russian, and Iranian joint venture partners would have looted Venezuela’s resources at the expense of the environment and its impoverished citizens.

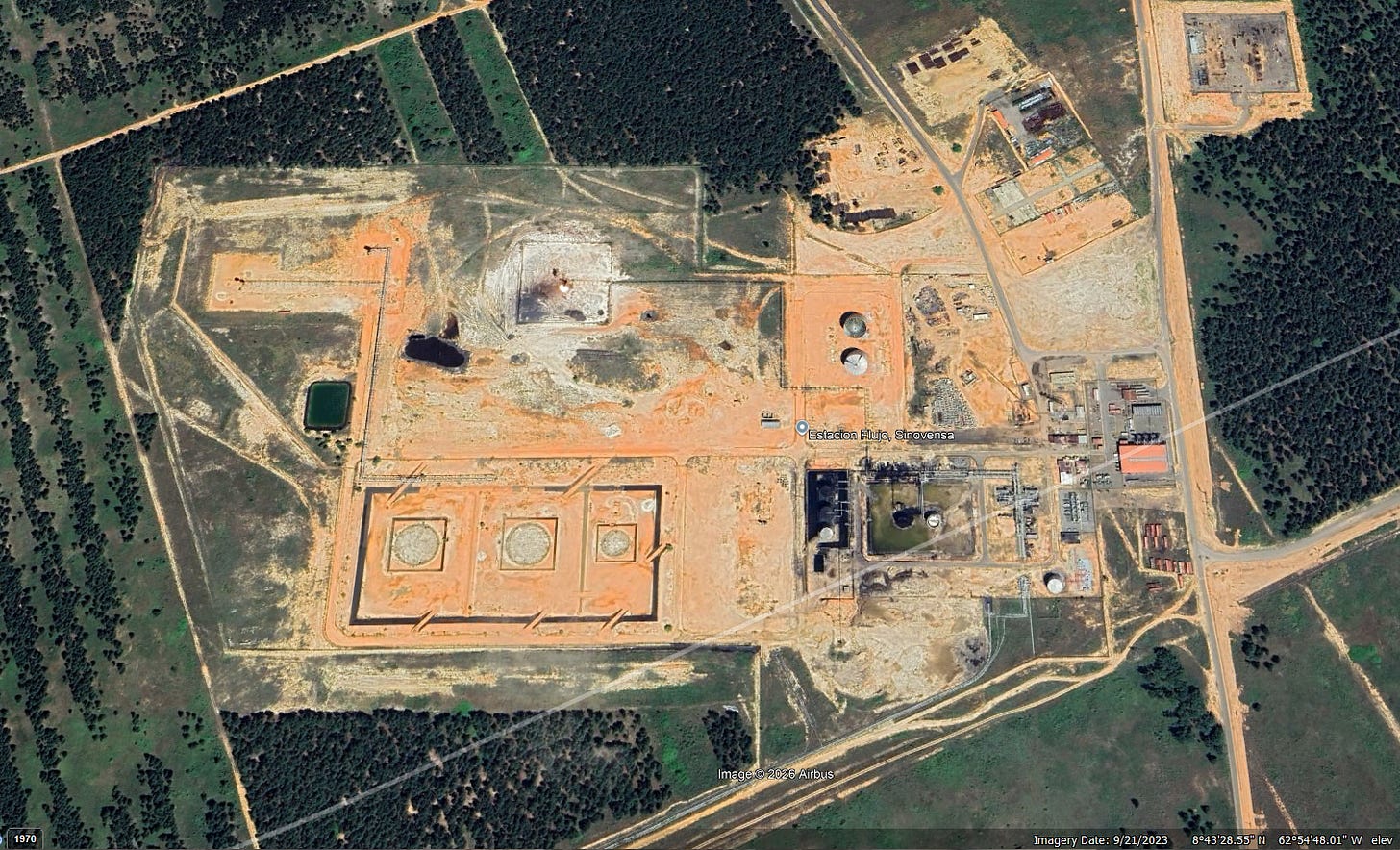

The PDVSA/Sinovensa production/flow station and crude treatment facility below, ~30 miles northwest of Guayana City in the Orinoco Belt, was still under construction at the time of this Google Earth satellite image in 2023. It handles well production, gas systems, and dehydration/desalting of extra‑heavy crude before it is sent onward.

Trump’s actions in Venezuela are about western hemisphere resources, specifically oil, natural gas, rare earths, gold, and other metals. And which sphere of influence controls them, the Chinese/Russian axis or America.

China, Russia, and Iran have been quiet so far about their Venezuelan oil claims and outstanding debt. How do these square with a President who told the CEO of an American major energy company he invited to the White House to ask for help “good writeoff!” after having $12 billion nationalized in Venezuela? We are about to find out.

Our final question is a refresher of the hard lesson learned in South America years ago by the only U.S. energy major still operating in Venezuela, whose CEO was present in the room when Trump met western energy executives at the White House days after Maduro was removed from office. Mike Wirth became Chevron CEO in 2018, two years after the dust settled from Chevron’s Texaco adventure in Ecuador. As such, no one in that meeting was better positioned to explain to Trump how the lessons Chevron learned about the risk of environmental litigation in Ecuador might make western majors reluctant to rush to Venezuela.

From 1964 to 1990, Chevron predecessor Texaco produced about 1.5 billion barrels of oil from its Oriente Basin concession in the remote Amazon headwaters of northeastern Ecuador. The year after terminating operations, Texaco was sued in an Ecuadoran court by indigenous woman María Aguinda Salazar on behalf of thousands of affected residents (“afectados”) from communities in the region. The widely publicized, class action lawsuit alleged health and environmental harms from extensive contamination blamed on Texaco’s operations (not those of the state oil company Petroecuador) and sought billions in environmental remediation damages and compensation.

After ten years winding through the Ecuadoran court system the case was refiled in Superior Court of Lago Agrio adding Chevron, who had acquired Texaco in late 2001. In 2011, eighteen years after the initial litigation, the Lago Agrio court found in favor of the plaintiffs and ordered Chevron to pay more than $18 billion in compensation. The judgment was later reduced to ~$9.5 billion but upheld by Ecuador’s highest court.

Shortly thereafter, Chevron filed a civil Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) action in Southern District of New York in 2011 against the lead attorney in the Ecuadoran case and several of his Lago Agrio plaintiffs. In that case, Chevron alleged fabrication of expert evidence, coercion of Ecuadoran judges, bribery, and other malfeasance, including the shocking allegation that lead counsel and his legal team actually ghost wrote the Ecuadoran judgment and paid the judge to sign it.

Chevron dropped its damages claims just prior to trial, seeking only equitable relief. That enabled a bench trial in front of Judge Lewis Kalplan instead of a jury trial.

In his 2014 ruling, Judge Kaplan found plaintiff’s lead attorney and the Lago Agrio team had engaged in a “pattern of racketeering activity” under RICO, including extortion, wire fraud, money laundering, obstruction of justice, witness tampering, and bribery of the presiding Ecuadorian judge. Kaplan granted Chevron equitable relief, holding that the Ecuadoran judgment was procured by fraud and unenforceable in the U.S.

In 2016, The Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed Kaplan’s decision, including the factual findings and the granting of equitable relief. The plaintiffs then sought review before the U.S. Supreme Court, but the Court declined.

Only Chevron knows its true costs for the fiasco it became embroiled in after terminating operations at its Oriente concession in Ecuador. But defending these types of class action cases is not cheap, and a $10 billion+ judgment could have easily eaten up to half of all the profits from Texaco’s 26 years of production in the Oriente.

With the ghost of Ecuador in the background, Western energy companies are being asked to go into largely decaying, dilapidated oil fields with corroding infrastructure, where many spills have occurred and are ongoing, and rebuild them. Even if they do so, they will be working in areas where decades of spills and releases have occurred, with little effort to remediate the problems by the actors who came before them.

The center of the production growth will be in the Orinoco Belt, a remote area with numerous indigenous tribes where oil spills, and for the last ten years illegal mining impacts, have caused heavy metals contamination in addition to oil spills.

If it does not go well, and a future Venezuelan regime nationalizes their assets, it seems likely (if not certain) that indigenous groups would be quickly seized upon by western NGOs with environmental lawyers in tow offering their “help.” So, while all the talk is about regime change, political certainty, constitutional and legal system changes, and government stability, we think environmental risk is an exposure flying under most people’s radars that could tip the scales for some western energy majors considering investing in Venezuela.

This would be a loss for Venezuela and its environment as well as its citizens, nearly 80% of whom are living in poverty in the beleaguered nation. Not just for the economic lift western energy companies could provide to an ideally more benevolent Venezuelan government through increased production and fixing deteriorating oil infrastructure. But specifically in the area of environmental remediation.

Western energy firms have the capital, technical experience, and latest remediation technologies to clean up the worst sites using technologies developed over the past several decades that are not widely used in South America. We would wager that more advanced remediation technologies like In-Situ Chemical Oxidation (ISCO), soil vapor extraction, air sparging, slurry walls, thermal destruction, and many more are not widely known about and employed across South America. American energy companies and their environmental engineers know how to use these technologies to gets sites cleaned up to conditions safe for human health and the environment efficiently (read: $), quickly, and properly.

Another good example is the enormous number of wells flaring gas from oilfield production in the Maracaibo and Orinoco basins. Luisa Palacios, the former Chair of CITGO in the U.S., recently noted that ~40% of Venezuela’s nearly 3 billion cubic feet (bcf)/day of produced natural gas is flared for lack of distribution and offtake capacity, squandering around $1 billion annually that could otherwise be captured to benefit Venezuela. More is certainly being lost to leaky infrastructure like valves, joints, fitting, and other surface equipment. Neither are helping the environment.

We close by noting that the money to remediate the urgent and long-term environmental risks from Venezuela’s oil and gas infrastructure and illegal mining will have to come from somewhere, and that will most likely be revenue from the sale of oil. Venezuelan oil already sells at a discount to other light, sweet, global benchmarks. Additional expenses – even for particularly good reasons like environmental remediation and restoration – function as costs on each barrel, and those costs cuts into the dollars left over to help Venezuela’s struggling populace and wrecked economy (people before planet in emergencies like this). And dollars left over in the form of profits to incentivize western energy companies to invest in Venezuela.

Environmental risks are on the table and the ghost of Chevron in Ecuador looms large. As such, President Trump will need more than bullying and threats to get western energy companies investing in Venezuela.

“Like” this post or we’ll tell DEA you were were a Maduro accomplice and have you sent to New York to be his cellmate.

Leave us a comment. environMENTAL is powered by readers like you. We read them all, reply to most.

We’re a reader supported publication. Please consider a paid subscription. Subscribe below.

Share this post. Helps us grow. We’re grateful for the assist.

This column provides a great description of the state of oil and gas production in Venezuela as well as mining. The extensive damage to the environment is appalling. Well done.

Someone needs to explain this to Trump in terms he might understand. It is the equivalent of building a new casino on top of a vast un-remediated Superfund site, within a lawless and ungoverned area of criminally controlled roads and infrastructure. It would require complete legal indemnification to existing and future discoveries of contamination, and a well armed Army to be able to take over those operations. Essentially it is a war zone and would require the laws of war to be in operation in order to function. Merely funding a local operator would not eliminate this risk. The deepest pocket is always the legal target, and the local employees subject to kidnapping and worse would still be tied to the investor. It reminds me of what I saw firsthand in Albania after they overthrew communism- oil covered lakes, drill rigs sitting ion wells with pipe in the ground rusting away, and lawless areas that were impossible to enter without risking one's life. Property ownership in Albania was in complete chaos, and I have no doubt this is analogous to Venezuela, which began by taking property away from landholders decades ago. It is a place where the man with the gun makes the laws. Even entering Iraq right after the war in 2003 would have had more certainty than Venezuela today.

Besides security and environmental issues the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act often makes it impossible (and has caused Chevron problems in the past in Venezuela) to run operations in a country like Venezuela, where bribery and graft are likely common business practices. Its a mess.