Politics Fear And Science (PFAS)

"It's like déjà vu all over again." – Yogi Berra

Fear and politics make it hard to remain true to science. The latest battle amassing on the border between environmental politics and science is a perfect example. In the past eighteen months, United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has undertaken the process of regulating the per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) known as “Forever Chemicals.”

History helps us frame the story. The pesticide DDT is an instructive example.

Rachel Carson’s famous 1962 book Silent Spring was instrumental in the birth of the Western environmental movement. The book asserted that modern industrial chemicals were killing humanity and nature, with the pesticide DDT a principal focus.

The ensuing media promotion and public outcry led to a variety of regulatory investigations and actions, culminating in the creation of EPA. EPA’s first Director, William Ruckelhaus (a Republican), banned DDT and amidst the controversy and appeals, appointed an administrative law judge to conduct hearings to evaluate the underlying science in 1971-72.

After seven months and 80 days of testimony from over 100 scientific experts, Judge Edmund Sweeney ruled that DDT:

“is not a carcinogenic, mutagenic, or teratogenic hazard to man” and that it “does not have a deleterious effect on freshwater fish, estuarine organisms, wild birds or other wildlife.”

When the Environmental Defense Fund appealed the decision, Ruckelshaus could (should) have passed the appeal to an independent jurist. But instead, he chose to rule himself, upholding the ban “on the grounds that DDT poses a carcinogenic risk to humans.”

Under pressure (including litigation) from environmental non-profits, international aid organizations threatened to withhold aid from developing nations who continued its use despite the fact that it was the most effective anti-malarial pesticide on earth. Many experts believe that this de facto ban caused tens of millions of preventable deaths in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Yet to date, no conclusive scientific evidence that DDT causes cancer in humans has been found; the same holds true about the other major fear: thinning bird eggshells. Even to this day, EPA’s website on DDT does not conclude either.

PFAS is another “Déjà Vu All Over Again” point in time for environmental risk, public perception, science, and politics. It is an opportunity to either spend taxpayer money wisely, for immediate, measurable risk reduction, or to scare people to death and embark on more wasteful “green” spending. It’s also an opportunity to increase public trust in science, or to further erode it in the wake of Covid-19.

We are at an inflection point, and the brewing PFAS storm is about to take one of these paths or the other.

In this post, we provide a brief overview of what PFAS are, where they came from and common products that include them. We provide links to some of the relevant science, and we discuss what EPA has already done, what they did last month, and the coming fork in the road.

Chemours’ predecessor DuPont invented PFAS around 1940. The two PFAS compounds that have attracted the most regulatory attention are perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) but there are thousands of chemicals in the classification.

PFAS have amazing properties including water, stain, oil, heat, and chemical resistance. DuPont’s Teflon was the most widespread early consumer application for PFAS. It has been beloved in U.S. households since FDA approved it (ironically) as a non-stick coating for pots and pans in 1960. Because their applications are so broad, the volume of consumer, commercial and industrial products containing PFAS are nearly endless.

They have been used in everything from stain resistant fabrics to microwave popcorn bags to food wrappers, pizza boxes, the coating on paper juice cartons and dental floss. They are present in Goretex fabrics, gun oils and many other commercial and industrial lubricants and coatings. The fire-fighting foams historically used to put out jet fuel fires at airports contain very high concentrations. We are still discovering products containing the compounds.

In keeping with our emphasis on abundant environmental ironies, PFAS are also used to save the planet! Chemours proudly pointed out in a “Renewable Energy Fact Sheet” that fluorinated polymers (PFAS) have widespread uses in wind turbines, solar panels and energy storage systems like lithium-ion batteries (EVs, electronics) and PEM fuel cells (“green” hydrogen).

The chemical industry claims fluoropolymers used in renewable energy applications are highly stable and low risk to human health and the environment. Some scientific studies disagree. Think about this the next time you see a wind turbine on fire.

It is impossible to recycle wind turbine blades and remove their fluoropolymer coatings. With an estimated useful life of 20-25 years, we are just now starting to dump huge piles of PFAS-coated wind turbine blades in landfills. Some of the highest concentrations of PFAS in groundwater have already been found at landfills across the U.S. How genius are we?

We began researching the emerging science related to PFAS and watching federal and state regulator’s postures after a landmark 2004 settlement between DuPont and a large group of citizens in the Ohio river valley. The class action litigation alleged a variety of cancers and injuries from PFAS to thousands of people living around DuPont’s (now Chemours’) Washington Works plant near Parkersburg, West Virginia and in the Ohio river watershed downstream. The case gave birth to the 2018 documentary The Devil We Know and the 2019 film Dark Waters.

U.S. manufacturers like DuPont and 3M voluntarily ceased production of PFOA and PFOS and certain of its precursor products around 2005. The “long-chain” PFAS compounds (known as such due to the number of fluorine-carbon molecules in a “chain” structure) such as PFOA and PFOS (and several others in the alphabet soup of PFAS) have been largely replaced by “shorter-chain” compounds thought to pose lower risks to human health and the environment.

But the key molecular backbone of PFAS is the chemical bond between carbon and fluorine, one of the strongest in all of nature. This bond renders them non-biodegradable meaning, without treatment or removal, their presence in soil, surface water, groundwater (think drinking water wells), and sediment, poses a possible risk to human health and the environment “forever.” If the science shows they are dangerous.

PFAS are highly mobile and travel far. They disperse in groundwater and can travel miles from a source. They are transported through the atmosphere far from production sources and have been detected as far away as the Arctic in polar bear blood serum.

The compounds are by now so ubiquitous, it is likely most people on earth have traces of it in their blood. It is even in the blood and muscle tissue of a portion of the U.S. whitetail deer herd.

PFAS have also accumulated in our food chain. In some areas, they become concentrated in the sludges of municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). Because these sludges are rich in nutrients, they have historically been “land applied” (spread as fertilizer) on agricultural fields across America. Atmospheric deposition (how polar bears got it, if not from eating tourists, fish, or garbage in landfills) is believed to have introduced PFAS into the food chain through air and rain.

The highest concentrations are commonly found in soil and groundwater at and near the industrial plants that manufactured it. High concentrations in groundwater are also common at airports that trained to put out jet fuel fires with it, and landfills that have accumulated trash containing it.

Wherever there are jets, a certain classification of fire-fighting foam containing PFAS known as Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (Class B or AFFF) has been the preferred extinguishing chemical due to its amazing heat resistant properties. For decades, FAA has required most civilian and DoD airports to conduct firefighting training by spraying AFFF on junk aircraft parts aflame in jet fuel. Again, ironies abound. An FAA sister regulator, the EPA, is on the verge of codifying cleanup responsibility into law – after their sister required it by law to be sprayed on to the ground in the first place. Twisted Sisters.

To provide some perspective on how widespread detections of PFAS already are, we credit the Environmental Working Group for this interactive GIS map:

So, how dangerous to human health and the environment are PFAS? No one knows for certain yet. A ten-year study was undertaken as part of the 2004 DuPont class action settlement. ~70,000 participants with documented exposure to the DuPont Washington Works plant were studied.

For those interested in the science, the “C8 Science Panel” website contains all of the scientific investigations conducted as part of the settlement agreement. Several EPA sites (links here, here and here) contain relevant studies released since the C8 Science panel concluded its work.

In the wake of the Dupont Washington Works publicity and early results from the settlement studies, in 2009 EPA issued its first Provisional Health Advisory on PFAS, noting:

Epidemiological studies of exposure to PFOA (and PFOS) and adverse health outcomes in humans are inconclusive at present.

Fear of the unknown fueled political pressure. In 2016 EPA revised the Health Advisory, greatly reducing the permissible lifetime exposure limits. In December 2021, EPA signaled their next regulatory step, requiring public water suppliers (your local municipal or private water system provider) to monitor 29 different PFAS compounds under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). In March 2022, EPA further (dramatically) reduced the lifetime exposure limits to the trace amounts shown in the graph below. Their announcement acknowledged that amounts this low may not even be detectable by many of the environmental laboratories used by municipal water systems. On this question, their website notes:

This means that while PFOA and PFOS may be present in drinking water in trace concentrations that cannot be reliably measured, water provided by these systems that test but do not detect PFOA or PFOS is of lower risk than if they are found.

The graph below shows the reduction in EPA’s lifetime Health Advisory limits on PFOA and PFOS, from the first advisory in 2009 to 2022.

At some point it seems fair to ask, could we be chasing ghosts?

By summer 2022, the big remaining regulatory question was: would EPA propose listing PFOA and PFOS as “hazardous substances” under Superfund, the supreme law of the land governing cleanup of hazardous substance releases? In August 2022, they did exactly that.

Then three weeks ago on March 14, 2023, they proposed National Primary Drinking Water Standards for six PFAS compounds under the SDWA. For the first time, EPA proposed a legally enforceable limit in drinking water, known as a maximum concentration level (MCL) for PFAS under the SDWA. What is the proposed MCL? Four parts per trillion for PFOA and PFOS, one part per trillion for four other target PFAS compounds.

To give you some perspective on how diluted anything measured in parts per trillion is, here are a couple of reference points. First, this graphic image from the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE) PFAS division provides a useful visual:

The 2016 Health Advisory of 70 parts per trillion equals about 3.5 drops of PFAS in a single Olympic size swimming pool. The March 2022 Health Advisory reduced that exposure limit to tiny fractions of a single drop of PFOA/PFOS in an Olympic size pool – 660,000 gallons of water. Setting aside the gross factor and scientific differences for a moment, consider that you could ingest a higher concentration of fecal coliform bacteria and urine at your community swimming pool every day this summer.

By stark comparison, EPA’s primary drinking water standard for vinyl chloride, the hazardous chemical burned after the recent Palestine, OH train derailment, is 2,000 parts per trillion. And the metal at the center of the movie Erin Brokovich (chromium) has an EPA primary drinking water standard of 100,000 parts per trillion. And DDT was permissible in baby food at a level of 5,000,000 parts per trillion (equal to 5 parts per million) prior to the ban.

The financial implications of listing PFAS under Superfund are enormous, likely in the trillions of dollars. Aside from cleanup costs, it invites litigation. Lots of litigation. The case that made the movie (and the person) Erin Brokovich famous was against a single corporation (PG&E) associated with a single utility plant site. Think about how ubiquitous PFAS are by comparison.

Under Superfund, taxpayers will shoulder much of the expense, including virtually all of the remediation costs at U.S. military bases – active and closed. We have heard quiet estimates that this cost alone could range from $10 billion to $100 billion, depending on cleanup standards and remediation technologies.

Some of the cost will be borne by a few large industrial chemical concerns like DuPont, its fluorinated chemical company spinoff Chemours, and 3M, including at their own plant sites. These liabilities will be in the forms of litigation by municipal water systems forced to treat at their wells (or locate new extraction wells for clean water supply), individuals alleging injury, and cost recovery/contribution actions by other “Responsible Parties” under Superfund law.

How much will all this cost? No one really knows. The answer largely depends on EPA’s regulatory actions. For now, we would hazard a guess that $10 billion to $1 trillion is a reasonable 30 year working cost estimate taxpayers will absorb. That’s just from federal facilities and orphaned industrial sites should PFAS get listed as hazardous substances under Superfund. If so, and the thresholds for groundwater cleanup are below ~20 parts per trillion (ppt), we could easily envision taxpayers spending $2+ trillion over 30 years.

The situation poses a major dilemma for the Biden administration. Public pressure is mounting to regulate PFAS under Superfund. A growing number of states have acted out of frustration with EPA’s slow reaction, a plurality of them imposing cleanup standards lower than EPA’s 2016 Health Advisory (70 ppt).

In more ironies, DuPont and Chemours are headquartered in Delaware, and the two companies have long-standing ties to Joe Biden in the state. If his EPA lists PFAS under Superfund, he can kiss goodbye a lot of Christmas cards (and campaign donations).

If EPA fails to list PFAS as a “hazardous substance” under Superfund, even if supported by a reasonable and cautious interpretation of the science, environmentalists will scream bloody murder. If that occurs, the disparate state regulations will still be enforceable and it will not be the end of the push for federal regulation. It will only encourage more.

This is another inflection point in U.S. environmental science, regulation, law, and politics. PFAS propaganda will be constantly in your face with no shortage of fear driven by the usual sources. Expect the chemical industry to tell you low-level exposure is harmless. Expect the environmental non-profits like Environmental Defense Fund and Natural Resources Defense Council to tell you that one part per trillion in your child’s blood will cause cancer.

The truth is, we’re not certain how dangerous each PFAS substance is, at what exposure level, and what the human health effects are. The scientific literature shows significant associations, correlations, and some evidence of certain cancers in animal tissue. Some action is warranted. The questions of which action, on what basis, and at what cost are the key.

PFAS have become so widespread since the 1960s that some broad evidence of human harm should be indicated in coarse, long-term human health data. The first two places we would expect to see that evidence are in life expectancy and cancer rates.

The below graph shows global life expectancy by region from the period 1961 to 2020. It shows that for 60 years, life expectancy has steadily increased across the globe:

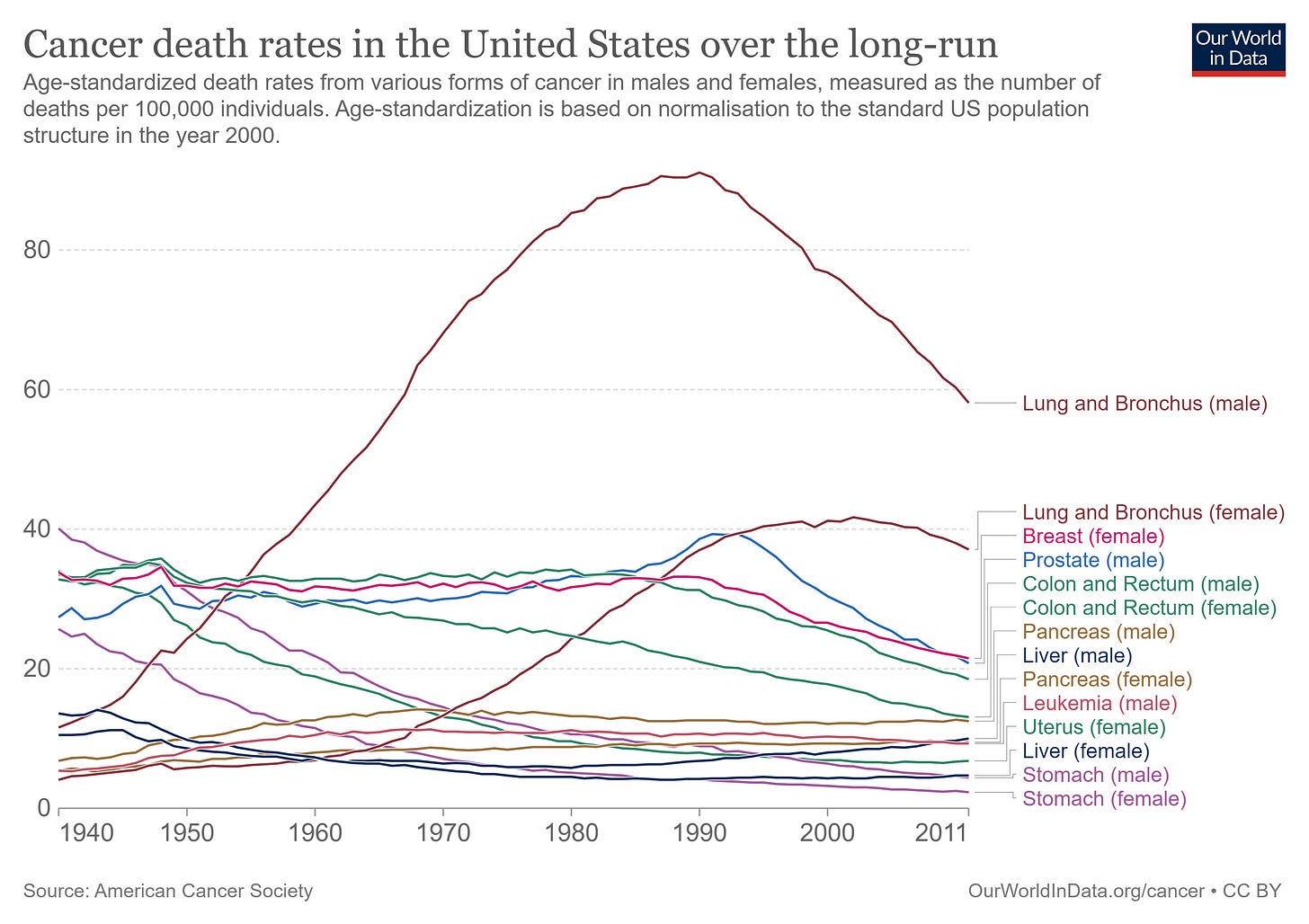

Does the data on cancer incidence suggest a poisoning of humanity by PFAS at a macro level? The below graph shows U.S. cancer rates from 1940 – 2011, the period from the beginning of widespread use of PFAS to ~6 years after major chemical manufacturers in the U.S. ceased making “long-chain” PFOA and PFOS):

Even if the human toll of the wrong policy decision is not a pile of bodies like DDT, it could certainly be a pile of money burned. Money that could solve lots of pressing human health and environmental problems.

A new report by the Copenhagen Consensus (CC) highlights the need to prioritize spending on environmental policies. Rank ordering the 169 UN “Sustainable Development Goals” based on cost/benefit, the CC finds that for $35 billion annually, we could implement twelve key goals, reducing annual premature deaths by 4.2 million globally. For reference, that amount is less than the annual U.S. spend for “climate change” under the Inflation Reduction Act ($369 billion over 10 years or ~$37 billion/year) conservatively. How many lives will be spared globally through the U.S. IRA expenditure over the next 10 years? We urge readers to review the new report and consider it in the context of our overarching theme about environmental and energy policy choices and the consequences on the developing world.

PFAS present another fork in the road, with fear in one direction and science in the other. Which path we choose matters. Will we take a step toward restoring public faith in science which has been badly shaken by climate fear mongering?

It’s like “déjà vu all over again.” We need to act wisely. Science, reason, cost/benefit, prioritization, and balance? Or fear, hyperbole, and politics? We will cover it all as PFAS plays out.

Tomorrow is our 4 month anniversary. Thanks to our readers and subscribers for your support! We grow through your shares, subscriptions, like and retweets.

We can hope logic dominates the future of PFAS regulation. Thank you for writing this up for review as well as you have. The comparison to municipal swimming pools is a very good way to get the average person familiar with concentrations.

So the specious statistical sophistry known as Linear No Threshold principle beloved of regulators the World over strikes again...