"When you come to a fork in the road.... take it." - Yogi Berra

William Stanley Jevons was a 19th century British economist whose 1862 book General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy contributed to the “marginal utility theory of value”. Put simply, the second slice of pizza may be even more satisfying than the first. But at some point – whether that’s the fourth, fifth, or sixth - the “value” of that “satisfaction” turns to zero, then negative.

In the energy arena, Jevons is better known for his 1865 book The Coal Question; An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal Mines. In The Coal Question, Jevons explores the paradox that increases in the efficiency of coal production in England would not result in the use of less coal and energy, but inexorably more, eventually exhausting the nation’s supply. This concept became known as Jevon’s Paradox.

Stanley Jevons died in 1882 at the age of 46 (drowned on the coast near Hastings). He did not live to see distributed electricity in his home country, or how Thomas Edison’s Pearl Street power station which opened in Manhattan, New York that year changed America and the West forever.

Jevons Paradox has stood the test of time to describe virtually every energy efficiency scenario imagined, from the production of more coal, more oil and more natural gas to the use of electricity inside your home. Wikipedia’s summary adequately describes the phenomenon:

In economics, the Jevons paradox occurs when technological progress increases the efficiency with which a resource is used (reducing the amount necessary for any one use), but the falling cost of use induces increases in demand enough that resource use is increased, rather than reduced.

In a strange sort of 21st century twist on Jevons Paradox, all savings in CO2 emissions from the global rollout of “renewables” will be lost in the additional energy consumption requirements of data centers, Artificial Intelligence (AI), electric vehicles (EV’s), cryptocurrency mining, heat pumps, EV and utility scale battery production, reshoring semiconductor production and “clean tech” manufacturing amid attempts to “electrify everything”.

How is this possible? Because wind and solar will not come close to providing enough electricity necessary to meet demand growth.

Why will wind and solar be insufficient to meet the rapid growth in electricity demanded by these technologies? What are Big Tech companies doing that proves they understand wind and solar cannot supply the power they need? And how does all of this set up for natural gas and nuclear energy to be the big winners in the long run?

We begin with a brief overview of anticipated future U.S. electricity demand, anticipated growth in wind and solar, and a few measures of the gargantuan amount of power required to support the new Big Tech, Clean Tech, and other power hogs.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), in 2023 U.S. electricity generation totaled about 4,178 Terawatt hours (TWhs). About 60% came from fossil fuels, 19% was from nuclear energy, and about 21% was from renewable energy sources.

In its last Annual Energy Outlook (2023), EIA projected only 188 TWh growth in net generation, and 221 TWh growth in total electricity use, from 2024 to 2030.

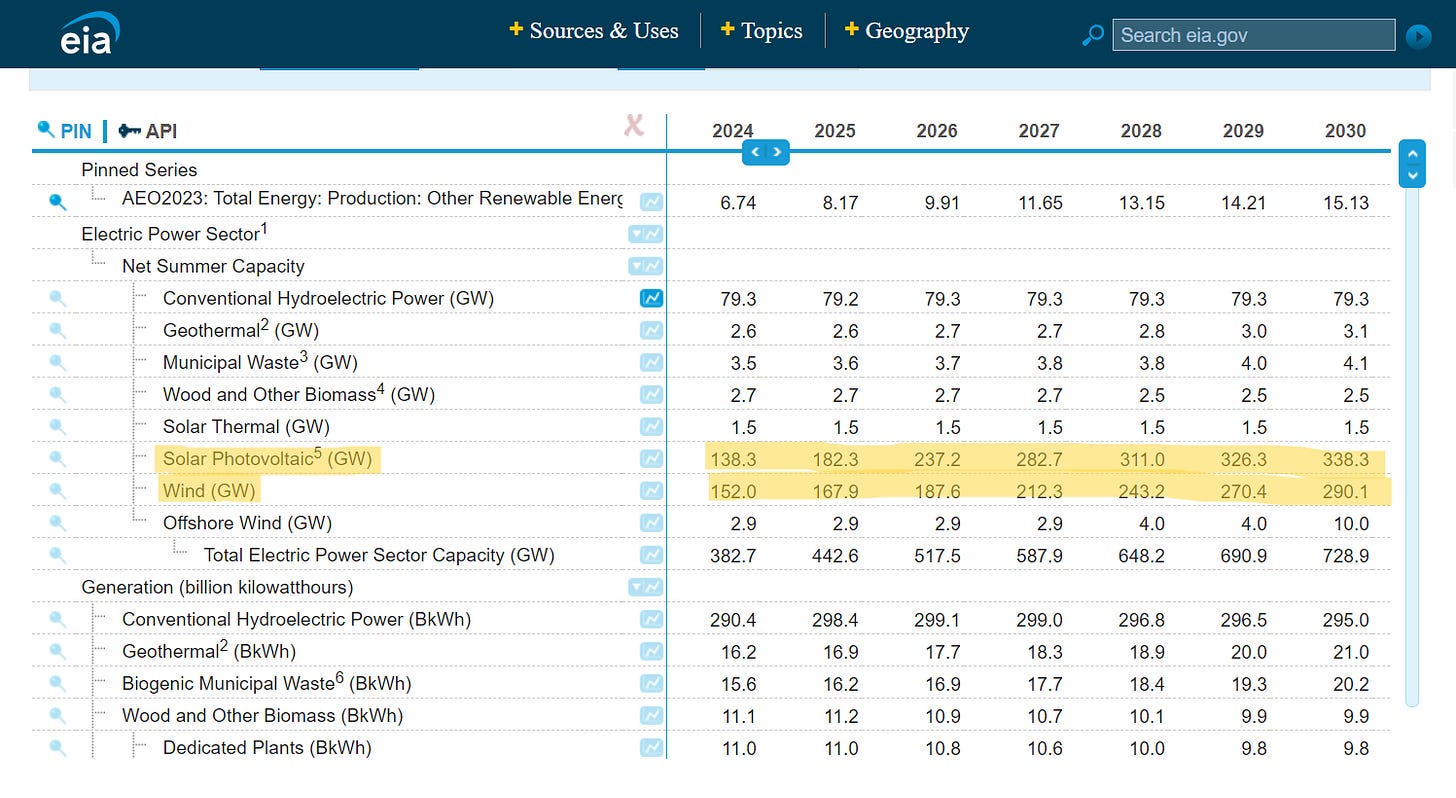

From the same EIA report we can see the projected growth in Gigawatts (GW) of wind and solar capacity for 2024 – 2030. (We ignore hydropower, geothermal, municipal waste, wood and other biomass and offshore wind. As the figures below show, they are generally irrelevant in the growth projections.)

In the table below, we list the growth for wind and solar, and assign capacity factors of 25% for the future solar generation and 40% to wind, rendering a reasonable estimate of their effective capacity growth in GWs. Despite growing by over 338 GW’s of capacity between 2024 – 2030, in round figures our effective capacity growth shows ~105 GWs:

At the same time, EIA projections include retirement of ~92 GWs of fossil fuel and nuclear power plants (of which 82 GWs are coal-fired plants) from now to 2030. While this forecast includes building ~66 GWs of gas turbine and combined cycle power plants, even that capacity faces regulatory uncertainty from the Biden administration’s pending fossil fuel power plant greenhouse gas emissions rule.

Some of the largest potential gaps in meeting electricity demand due to coal-plant retirements are in some of the markets expecting enormous growth of Big Tech electricity hogs: data centers. PJM and MISO are the Regional Transmission Operators serving most of the Mid-Atlantic (PJM) and Midwest (MISO). In joint comments to EPA last fall, PJM, MISO and two other large grid operators expressed serious concern that EPA’s proposed power plant rule could result in material, adverse impacts to the reliability of the power grid.

PJM and MISO have been warning the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) that the pace of coal-plant closures exceeds replacement capacity, threatening their reliability. The North American Electric Reliability Council (NERC) has reported similarly.

Between the planned growth in wind and solar, the planned coal plant retirements, and the rapidly changing projections for electricity demand on the ground, there is clearly a growing disconnect that is becoming more apparent by the month. A recent Washington Post article provides a useful starting point:

Data center operators are clamoring to hook up to regional electricity grids at the same time the Biden administration’s industrial policy is luring companies to build factories in the United States at a pace not seen in decades. That includes manufacturers of “clean tech,” such as solar panels and electric car batteries, which are being enticed by lucrative federal incentives. Companies announced plans to build or expand more than 155 factories in this country during the first half of the Biden administration, according to the Electric Power Research Institute, a research and development organization.

The Biden administration’s “aggressive” (read: impossible, despite being forced) plan to make the U.S. light duty vehicle fleet 100% electric by 2040 is one example. That effort alone could add ~835 TWh’s of U.S. electricity consumption. Using merely a third of that figure for EV adoption to 2030, the additional electricity consumed still exceeds the EIA’s projected 221 TWh growth in electricity use to 2030.

Next, we have the industrial electricity demand from the wide variety of “clean tech” manufacturing from those 155 wind, solar, EV battery, utility scale battery storage, hydrogen production, semiconductor, and other industrial plants referenced above. We have seen no gross electricity demand figures, but we can surmise it is non-trivial.

Now pour on cryptocurrency mining. According to Ben Hertz-Shargel, global head of grid edge at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie, cryptocurrency mining used a fifth as much electricity in 2022 as global centralized data computing and data transmission combined. One recent estimate suggests Bitcoin mining uses around 127 TWh of electricity annually – roughly Norway’s entire annual electricity consumption.

“That is stunning,” said Hertz-Shargel, as it means that cryptocurrency mining is using a fifth of “all of the fruits of the internet revolution, industrial revolution, the cloud and AI industrial revolution.”

According to Hertz-Shargel, in a global context, this could mean that the boom in the rollout of renewables risks being in some part cancelled out by a parallel boom in the energy demands of Bitcoin. EIA estimates that 2023 electricity consumption by cryptocurrency mining could be up to 91 TWh’s or 2.6% of total U.S. consumption. And that was before the Securities and Exchange Commission approved Bitcoin ETFs.

Last comes the big enchilada no one planned for, or understood the implications of, in terms of electricity demand even five years ago: AI. In its December report The Era of Flat Power Demand is Over, U.S. electricity grid consultant Grid Strategies noted (emphasis added):

According to the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), data centers currently represent 2.5% of U.S. electricity consumption. By 2030, BCG expects energy use to grow from 126 TWh to 335 TWh (<200 TWhs), or demand of 17 GW to 45 GW.

New generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) is a significant driver of BCG’s estimate, with 2 GW of GenAI-related load in the base case and possibly an additional 7 GW of GenAI load online by 2030. At this higher end, BCG estimates that data centers could consume 7.5% of all electricity in the U.S.

The epicenter of data center electricity load growth in the U.S. is Loudon County, Virginia. Known as “Data Center Alley”, it is the world’s largest data center market, and home to around 35% (~150) of all known hyperscale data centers worldwide.

Dominion Energy serves most of this load in Virginia. Dominion describes the situation as follows:

“In the Company’s service territory, the industry has grown on average 0.5 GW a year in the last three years. Since 2019, the Company has connected 75 data centers with an eventual capacity of 3 GW.”

For perspective, each of the two large AP-1000 nuclear reactors recently completed at Plant Vogtle in Georgia are just over 1 GW. And it took more than a decade to build them.

On a recent episode of the Decouple Podcast, Chris Keefer’s popular guest James Krellenstein noted that:

Just over 2020 - 2022 we saw power use jump from around 116 TWh in VA to 133 TWh, more than 15 TWh’s in growth just in that one region alone, almost all that is dominated by the increase in data centers. So, this load growth that we’re starting to see being driven by AI is not a hypothetical thing. It is happening now.

Last fall, utility Arizona Public Service began turning down requests from large data center projects. It noted that some individual customers had requested almost 2 GWs of electricity.

The chart below from a 2023 McKinsey & Co. report shows that the U.S. is poised to add 13 GWs of electricity demand from data centers alone from between 2023 and 2030. The 32 GWs of total data center demand expected by 2030 equals more than a third of all of the available electricity generation from America’s remaining nuclear power plants.

In 2023, Georgia electric utility Southern Company (parent of Georgia Power) revised its electricity demand forecast to reflect the build out of large data centers and other industrial loads. The company’s updated forecast projects 6,600 MWs (or 6.6 GW) of demand growth through winter of 2030, an amount 17 times greater than the previous forecast only a few years earlier.

Perhaps the biggest tell of all is not coming from the utilities, RTOs, or actual energy generators, but from some of the same Big Tech companies who spent the last decade cloaking themselves in “sustainabilchemy” sacraments. Despite pouring billions into wind and solar projects around the world for the stated purpose of making their operations “carbon neutral” solely on the back of wind and solar energy, today their actions speak to a different reality.

A December 2023 Wall Street Journal piece AI is Ravenous for Energy. Can it Be Satisfied? notes (emphasis ours):

Microsoft is working on using its own AI to speed up the approval process for new nuclear power plants—to power that same AI. The company is also betting on fusion power plants, inking a contract with a fusion startup that promises to deliver power within about five years—a bold move given that no one in the world has yet produced electricity from fusion.

Constellation Energy, which has already agreed to sell Microsoft nuclear power for its data centers, projects that AI’s demand for power in the U.S. could be five to six times the total amount needed in the future to charge America’s electric vehicles.

At the World Economic Forum in January, Open AI CEO Sam Altman said, “We do need way more energy in the world than we thought we needed before. We still don’t appreciate the energy needs of this technology.”

All of these realizations have resulted in state legislative efforts to delay coal-fired power plants retirements, as noted in this Energy & Environment News article last month. “All of these legislative efforts come on the heels of multiple reports by electricity reliability organizations like NERC and others warning of looming generation shortfalls.” Bloomberg noted the same phenomenon in a January article AI Needs So Much Power That Old Coal Plants Are Sticking Around. (We surmise it was painful for Michael Bloomberg to read that headline on his own news site.)

A Wall Street Journal article two weeks ago conveniently titled Big Tech’s Latest Obsession Is Finding Enough Energy suggests exactly how much Big Tech is willing to bet its electricity-gobbling future on wind and solar. Reporting on the buzz at the recent annual CERAWeek energy event in Houston, the Journal notes (emphasis added):

This year, the dominant theme of the energy industry’s flagship conference was a new one: artificial intelligence.

Tech companies roamed the hotel’s halls in search of utility executives and other power providers. More than 20 executives from Amazon and Microsoft spoke on panels. The inescapable topic—and the cause of equal parts anxiety and excitement—was AI’s insatiable appetite for electricity.

Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates told the conference that electricity is the key input for deciding whether a data center will be profitable and that the amount of power AI will consume is staggering.

If you are wondering why California wouldn’t be a natural location for large data centers, Bill Gates just let the cat out of the bag. At about double the U.S. average electricity cost, the chance that California will outcompete Texas, Georgia, Virginia or other states with large metro areas and 50% lower electricity rates is Slim and None. And Slim left town on the 4:00 Greyhound for Houston.

Ernie Moniz, a trained physicist who served as Secretary of Energy under the Obama Administration, is solidly in the camp that climate change is a serious problem. The same Journal article notes Moniz’ comments at CERAWeek (emphasis added):

Former U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz said the size of new and proposed data centers to power AI has some utilities stumped as to how they are going to bring enough generation capacity online at a time when wind and solar farms are becoming more challenging to build. He said utilities will have to lean more heavily on natural gas, coal, and nuclear plants, and perhaps support the construction of new gas plants to help meet spikes in demand.

“We’re not going to build 100 gigawatts of new renewables in a few years. You’re kind of stuck,” he said.

It is hard to argue against Moniz’ position. Substack author Robert Bryce has documented the difficulty siting wind and solar across America. If you are not familiar with his excellent “Renewable Energy Rejections Database”, you can find it here.

We are far behind building the necessary transmission lines as well. A U.S. Department of Energy document from April 2022 notes, “despite significant expenditure on transmission upgrades in recent years, the number of miles of newly built high voltage transmission has declined over the last decade from an annual average of 2,000 miles from 2012-2016 to an average of just 700 miles from 2017- 2021.”

Perhaps the most prescient among the comments at CERAWeek were offered by Toby Rice, CEO of U.S. natural gas behemoth EQT:

“Tech is not going to wait seven to 10 years to get this infrastructure built. That leaves you with natural gas.”

We close by noting what should be obvious at this point. While wind and solar will provide some of the growth in U.S. electricity demand, it will not come close to newly evolving projections of electricity demand like the ones we’ve noted above.

Big Tech’s data centers require 24/7/365, 8760 hours non-stop annual high-quality, uninterrupted, non-intermittent electricity. Battery storage systems with 4-8 hours backup will not solve that problem. Knowing these realities, Big Tech is not going to bet the farm on wind, solar and battery storage.

Natural gas is a layup. Some day, nuclear power will provide most of the electricity demanded by Big Tech and the rest of U.S. industry and consumers. But not without “environmentalists” first doing everything they can to stop it.

In the end, we do not believe it will matter. Big Tech will steamroll Big Green to get the power it needs. Michigan Governor Whitmer’s recent support for Holtec’s restart of the Palisades nuclear complex in her state is proof positive even Democrat loyalists recognize the political peril associated with intermittent electricity, lack of electricity, sky-high prices, and the inability to serve Big Tech donors.

What is the lesson here? You can have your AI, your data centers, your “clean tech” manufacturing, your EVs, and your reshoring semiconductors. But you can’t have it with an electric grid powered by 100% wind, solar, and hydropower in an advanced industrial nation like the U.S.

Natural gas and nuclear are about to become Big Tech’s new BFFs.

Watch what happens next.

“Like” this post or get hooked up to a stationary bike to keep data centers powered.

Leave us a comment, we read all of them!

Subscribe to environMENTAL for free below.

Share this post liberally!

Nuclear power can come close to being "too cheap to meter".

It's the excessive regulations, based on the debunked hypothesis of the Linear No Threshold (LNT) concept that has resulted in undeserved fear of radiation and huge unnecessary cost to comply with non-sensical rules.

Please see the publications of Edward Calabrese on this subject, as well as the information available at:

radiationeffects.org

the website of Scientists for Accurate Radiation Information.

Thank you for supporting the generally obvious with data and detail.

Environmentalist opposition to nuclear is irrational - unless of course their real desire to limit growth (think population) is acknowledged