More Until Less

The “energy transition” and “peak oil” are myths, all energy is additive and symbiotic, and the demographic factor that quietly changed everything.

“When it comes to carbon emissions, the world is going to ignore climate alarmism, continue to burn fossil fuels at an ever-growing rate, and roll the dice on the consequences.” – Doomberg

Humans are an amazing species. We are incredibly innovative. We turn earth’s resources into materials using energy surpluses we create, harnessing the powers of physics and chemistry we learned to unleash. That more and more humans use more and more resources, which has negative impacts on land, air, water, and earth’s atmosphere is only the obvious part of the story.

Predictions of environmental crises, collapses and their causes are nothing new. From food production and population in the 1800s, to resource exhaustion in pursuit of infinite growth on a finite planet, to “climate change” caused by hydrocarbon combustion, humanity has had one foot out the door by its own making for over 200 years.

English economist Thomas Robert Malthus (An Essay on the Principle of Population), the U.S. Geological Survey in 1919 and M. King Hubbert in 1956 (peak oil), Stanford Biologist Paul Ehrlich in 1968 (The Population Bomb), and Club of Rome in 1972 (The Limits to Growth) all effectively made the same mistake in retrospect: assuming backward looking data that failed to account for innovation and technological change could reliably predict a future which they could not even conceive.

In present times, common misunderstandings about of the history of energy and material production and their inextricable relationship have clearly led to mistakes pursuing solutions to “climate change.” The net effect is that the “energy transition” portrayed as the solution is a house of cards. In a new book, one French energy historian makes the case that it is a meaningless term and brings the receipts to prove it.

Malthus and Ehrlich made another critical mistake. Ironically, that error is now the ultimate solution to not only climate change but food production, resource depletion, contamination of air, land, surface water and groundwater, and a host of other environmental concerns. Today, most predictions of climate and environmental doom and the models on which they rely fail to properly account for the effect of that same variable.

How are energy and material production deeply connected, and their histories misunderstood? What key mistake (other than technology) that crushed Malthus and Ehrlich also carried into climate models and predictions of climate disaster? And what does all of this mean for climate and environmental panic and the “energy transition” in the long term? Get out your hearing and eye protection, it’s time to blow up more narratives.

On a recent episode of his podcast The Great Simplification, environmentalist and former Wall Streeter Nate Hagens spoke with a guest who put the lie to the “energy transition” narrative in a most insightful and unique framing. In his new book More and More and More French historian of the environment, technology and energy Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, documents that all energy is additive, energy and material production are inextricably symbiotic, “nonreliables” merely reduce carbon intensity, and “energy transition” is nothing more than a political slogan.

Summarizing Frezzos’ argument, history shows that human societies do not undergo "energy transitions" where new energy sources replace old ones. Rather, energy systems grow through additive accumulation and symbiotic dependencies.

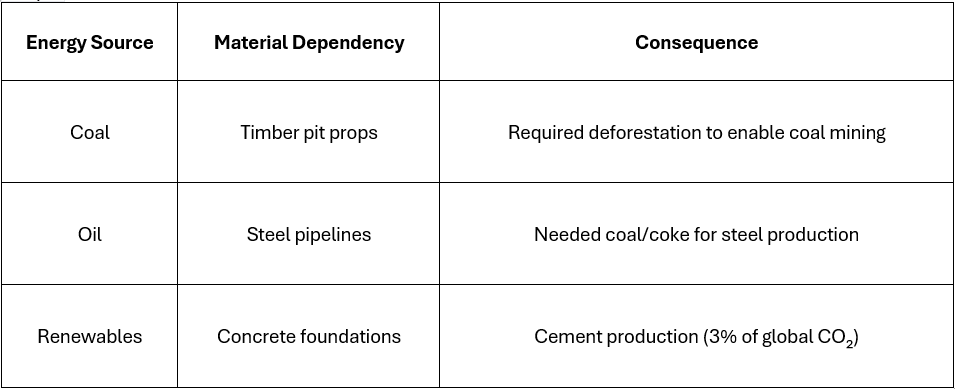

Consider a few examples Frezzos outlines in More and More and More:

Coal required more wood:

20th-century Britain used 4.5 million cubic meters/year of timber pit props to mine coal - 30% more wood than its total 18th-century firewood consumption.

Rail networks (enabled by coal) consumed vast timber for railroad ties to move the coal by train.

Oil amplified coal use:

Post-1950s mining technologies (hydraulic roof supports, coal cutters) developed in declining European mines were exported to China, enabling unprecedented coal extraction there in the 21st century.

Oil-powered chainsaws and trucks made timber cheaper and more accessible, increasing wood consumption.

Modern "renewables" rely on fossils:

Solar panels/wind turbines require hydrocarbon-derived steel, cement, and rare earth mining. Most of that mining is performed using diesel.

Global timber use doubled since 1960, with 2 billion people still relying on firewood - twice the energy output of nuclear power.

As if this were not enough to cause “environmentalists” heads to explode, it gets worse: there is an undeniable and unavoidable symbiosis between energy and materials, and energy systems are inextricably linked to material flows. Below are merely three of Frezzos’ examples:

The reality of this self-reinforcing feedback loop combined with human population and consumption explains the title to Frezzos’ book. More humans, more materials, more energy.

His historical analysis challenges long-held beliefs about past, present, and future energy “transitions”, including:

1. The Industrial Revolution was not a wood-to-coal shift

Britain's 20th-century timber consumption for coal infrastructure exceeded pre-industrial firewood use, disproving narratives of coal replacing wood. Charcoal use in African cities like Lagos (2 million tons/year) exceeds 19th-century France's total wood consumption, a feature of urban demand and energy poverty rather than "backwardness."

2. "Old" energies remain dominant

Energy from global firewood use (2 gigatons/year) dwarfs nuclear output. Modern mining depends on 1950s-era technologies originally developed for European coal mines.

3. Growth enables energy expansion

Comparisons between the rapid buildout of “green” tech and infrastructure for “climate change” and the Industrial Revolution ignore how fossil infrastructure required increased extraction of “finite resources” and exacerbated exploitation and environmental damage. Renewable expansion today follows the same pattern of additive growth rather than substitution, simply shifting the environmental damage to developing countries.

By virtue of the “energy transition” that isn’t, we slowly reduce the CO2 intensity of the economy and the emission of actual harmful pollutants of all types per unit of production. The technologies being used (e.g., Spinning Green Crucifixes™) are not “new” or revolutionary, they also use enormous amounts of resources and have negative environmental impacts, they can’t be deployed everywhere, and they have to be replaced every 15-30 years.

We sure are glad we were not the ones who had to break this bad news to “environmentalists” and their NGOs, celebrity environmental spokesclowns like Jane Fonda and Mark Ruffalo, and regressive progressive western Charlaticians™. But they seem to like academics (e.g., civil engineer Mark Z. Jacobson of Stanford) and Frezzos is one, so maybe his message will find purchase where it is most needed.

Viewing the combined problems of “climate change,” resource depletion, environmental degradation, and loss of ecosystem services (ocean, atmospheric, terrestrial) through Frezzos’ lens of More and More and More could easily lead to depression about the future of humanity and the environment. Sadly, significant numbers of young people hesitate (or even decline) to have children for this reason.

Frezzos and Hagens both believe “degrowth” is a key part of the solution. We do not.

In our view, “degrowth” is anti-human. Given clear demographic trends, it is not even necessary.

Something that was missed in all of the environmental and climate panic over the last several decades (and that Frezzos, Hagens, climate scientists and many others seem to miss) has changed so dramatically that, in our view, it renders all such worries moot in the long run: birth rates plummeted. A population crash awaits humanity.

Rapid population decline has enormous consequences for future energy use, consumption of resources, and greenhouse gas emissions, not to mention hazardous air pollutants and the contamination of air, soil, surface water and groundwater. We believe the consequences of rapidly declining birth rates and the coming population crash have been overlooked by climate modelers, politicians and fear mongering environmental NGOs. For ~30 years, climate and resource modelers used future global population assumptions that were never realistic.

We do not believe these errors were intentional. But the fact that population projections turned out to be badly mistaken is obvious in hindsight.

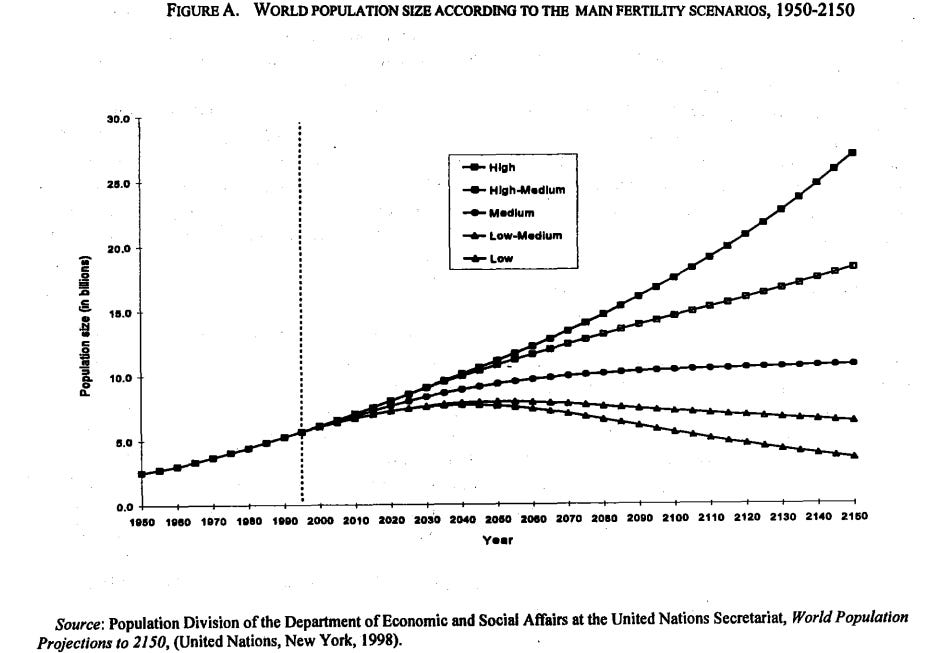

For example, three years before the United Nations (UN) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued its Third Assessment Report (2001), the UN issued this projection of global population out to the year 2150:

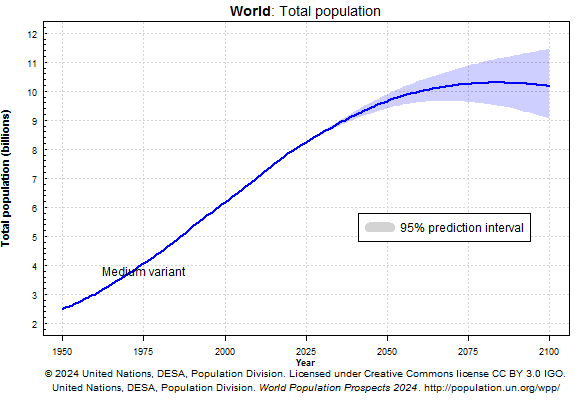

Readers will note that the “High” and “High-Medium” estimates reach a range of ~14 billion to ~17 billion by 2100. How does this compare to estimates produced by the UN today? Quite differently.

The UN now projects that earth’s population (currently ~8.2 billion) will reach 9.7 billion by 2050 before peaking in the mid-2080s at about 10.3 billion.

Compare the UN’s 1998 and 2024 population projection graphs above. Consider the difference: ~4 to 7 billion extra humans by the year 2100, with population continuing to rise for 50 more years in the 1998 projection. A peak in the mid-2080s at 10.3 billion in the 2024 projection.

That massive revision in population projections occurred within ~25 years. Few saw it coming.

Now consider the consequences in terms of energy, resources, food, and consumption. Four to six billion fewer humans mean a lot: fewer mouths to feed, fewer people to transport, less electricity demand, consumption of resources, and emissions of pollutants (to air, land and water) than were projected at the turn of the century, or even 15 years ago. For those worried about greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, including carbon dioxide and methane, billions fewer humans means less of those, too.

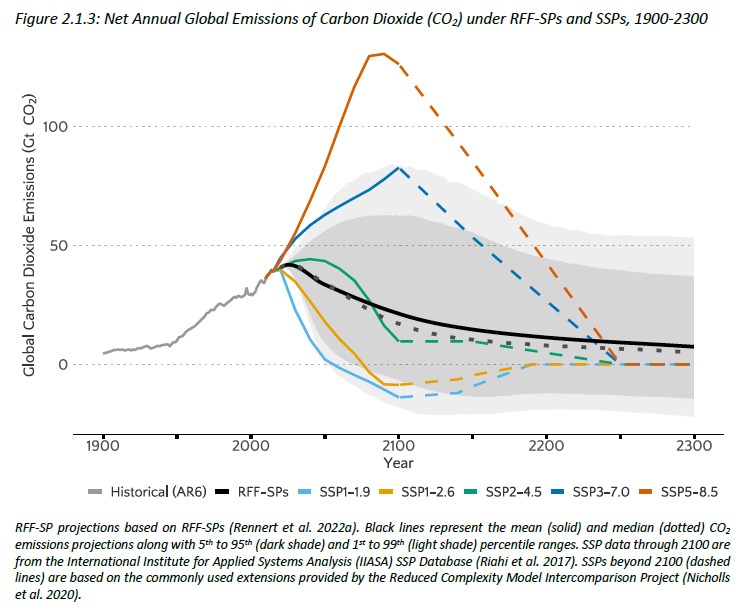

We have hypothesized that more than two decades of fear mongering over runaway “global warming” then “climate change” were rooted in population assumptions that turned out to be terribly wrong. As we noted in The Population Bombing in March 2023, we suspect this factored heavily into early UN IPCC emissions scenarios. Billions who would never existed and would never emit GHGs, using technologies that would not change much, partly explain dire projections extrapolated from “emissions scenarios” like the infamous RCP8.5 and its progeny (represented by the orange line in the graph below from that post):

So, here we are again: Failure to account for technological change, underestimating human innovation, and population estimates that turn out to be badly overstated. Move over Malthus. Slide to the side Paul Ehrlich. Make room for another chair at the table, Club of Rome. (Will we ever learn?)

There are two proven solutions for lowering human birth rates on planet earth. In terms of human freedom, flourishing, happiness, and advancement, one is right, the other is wrong.

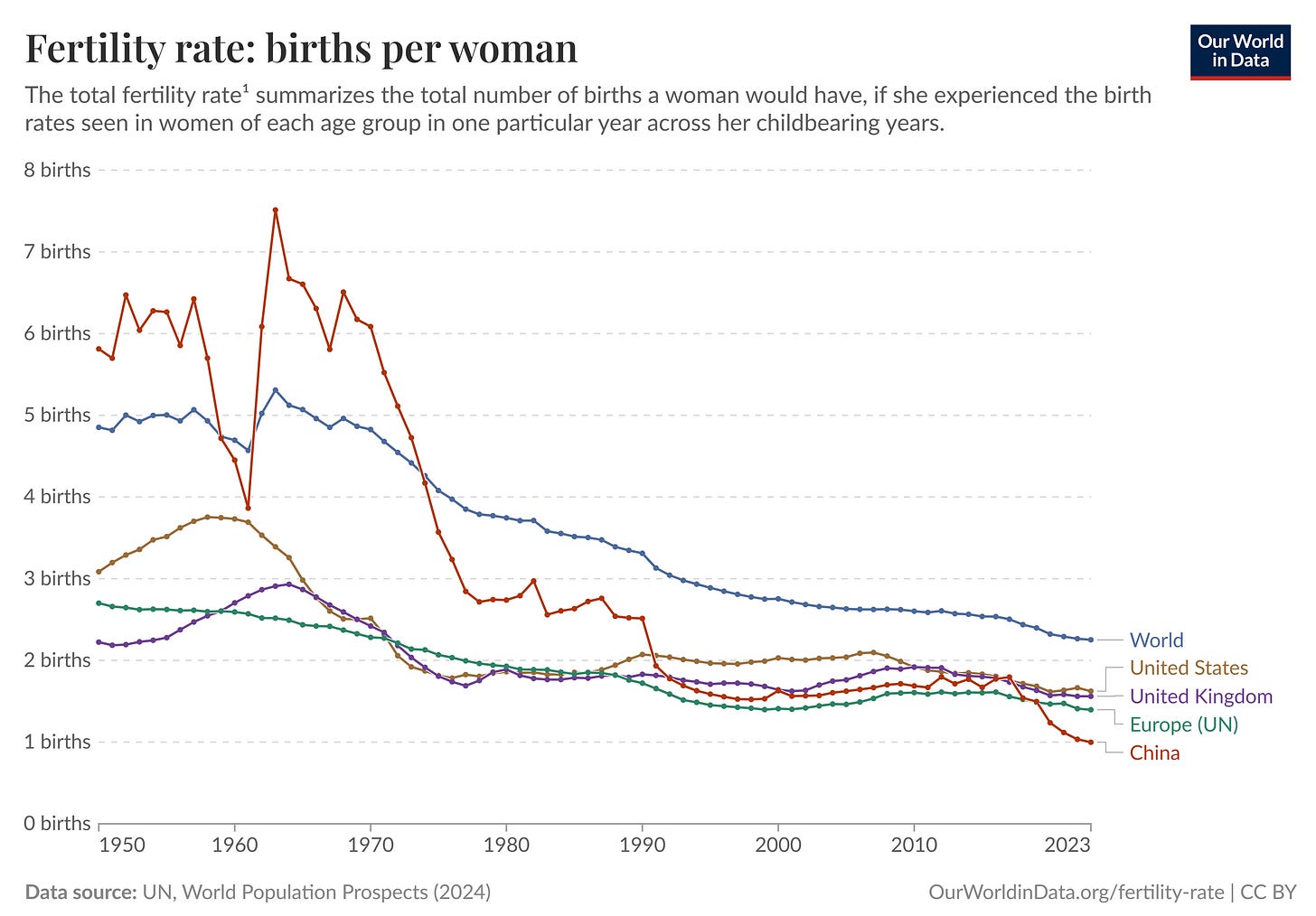

The first - the tyranny and force of Statism – is the wrong way. China’s “one-child” policy is the global standard.

The policy that lasted for over thirty years (1979-2015) was certainly “successful,” if birth rate is the only measure (~40% reduction over ~35 years, from 2.7 births per fertile mother to 1.7). If infanticide, a generation of men who cannot find wives, and an aging population and a declining workforce incapable of sustaining your tyrannical, repressive (if efficient!), Statist regime are irrelevant, that method works. The policy is estimated to have prevented 400 million babies.

It would be fair to say that increasing prosperity over the last decade of China’s “one child” policy also contributed to its rapidly declining birth rate. On the other hand, at 1.0 births per fertile mother today, China is in a demographic doom loop from which it will likely never recover, as the nation’s population drops from 1.4 billion to ~700 million by the end of this century, with some Chinese estimates even lower (the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences estimates 525 million). The social and political consequences of a depopulation that large that fast could eventually threaten the Communist regime’s control.

The second way is the manner in which the advanced nations reduced their birth rates, without the need for tyranny or force. All they did was enable the conditions for human prosperity and get the hell out of the way (if badly in the last quarter century).

What happened? Simple. People became wealthier. Wealthier people have fewer kids. In purely economic terms, the global data seems to confirm that in more urbanized, advanced, affluent societies, children are apparently a liability, not an asset. Or, more precisely, one child (maybe two) is an asset. Any more than that are liabilities. This is not a value judgment; it is a demographic conclusion from empirical data. Judge for yourself:

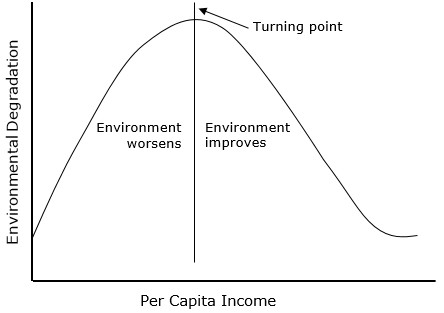

Along the way, another funny thing happened. Once citizens of advanced nations had their basic needs met and began to experience security, then prosperity, they realized that the very industrialization that raised their standard of living also caused significant pollution of air, land, and water which was harming them.

So, they demanded change. They passed laws, made tradeoffs, and began to find balance. Slowly, prosperity increased while pollution per unit of production decreased at the same time. In graphic terms, here is what actually happened, depicted in a simplified form known as the “environmental Kuznets curve” (named for Russian American economist and statistician Simon Kuznets):

Ironically, based on empirical evidence across the advanced world, while it may be counterintuitive, the best way to achieve rapid population decline without embracing the self-induced, misery-inflicting, anti-human “degrowth” agenda is to help the developing world reach our living standards as quickly as possible. That will require access to affordable, reliable, abundant, on-demand forms of energy.

Neo-Malthusian “environmentalists” will scream that even attempting to bring ~7 billion people up to our living standards would render the earth inhabitable and exhaust its resources before that could ever be achieved. That theoretical plausibility ignores what Julian Simon taught Paul Ehrlich the hard way about the failure to anticipate technological change, market signals, human ambition and problem solving. Or what people like recently confirmed U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright and other innovators did to unlock hydrocarbon resources King Hubbert considered technologically and economically impossible in his time.

Nearly 7 billion people living outside of the G7 nations are going to rely on hydrocarbon energy to develop economically, consume, and try to achieve our living standards. We would be ignorant and/or malevolent to attempt to stop them under the auspices of resource depletion or planetary and environmental concerns far into the future.

In a December 2023 post Meat in the Middle, Doomberg put it this way:

We have long held the view that the progressive environmental left is asking for the impossible—a global populace voluntarily lowering its living standards to abate intangible risks that might materialize far into the future—and that pressing for such degradation is the ultimate political dead end. The world is simply going to roll the dice on climate change and manage the consequences accordingly.

There is no escaping the symbiotic nature of materials and energy, there is no “energy transition,” and humanity is going to produce and consume, More and More and More, just as Jean-Baptiste Frezzos’ book title suggests. More wood, more hydrocarbons, more GHG emissions, more fertilizer, more cement, more steel, more plastic, more cars, more buildings. More food, more useless consumer goods, more material things people don’t need. More pollution, higher atmospheric CO2 levels, and more negative environmental impacts to air, land, water, biodiversity, ecosystems, and animal and plant species.

Until the population crashes, and then less. And that is going to occur not in one thousand or ten thousand or a million years, but within two centuries or less.

In the meantime, technology and innovation will continue to slowly improve resource efficiency and reduce emissions per unit of output. All the “kit” known as “alternative energy” will do little more globally than reduce the growth in hydrocarbon energy, not replace it.

Once the population crash begins, it will be swift and disruptive, economically as well as socially. Ironically, Paul Ehrlich gave an opinion about five years ago that looks like it might be prescient (especially by comparison to his, ahem, earlier predictions). In a March 2018 interview, he stated that he believes “the optimum human population for planet earth would be in the range of 1.5 – 2 billion.”

Good news, Dr. Ehrlich. That is going to occur, unlike what you envisioned back in the 1960s and 1970s. And much sooner than you could have imagined, too.

We close by noting that as long as freedom and political and economic structures and institutions encourage humans to ambitiously innovate, our extinction is orders of magnitude less likely to result from any combination of climate, biodiversity, depletion of hydrocarbon energy, water or other resources or other environmental fears than by sheer lack of desire to reproduce. We will keep doing more damage to the planet, and likely to ourselves, until we are less.

More, until less. And the latter is clearly coming.

“Like” this post or you’re first in line for extinction.

Leave us a comment. Refills the tank. We read every one, respond to most. The engagement helps the algo.

Subscribe to environMENTAL for free below.

Share this post. Helps us grow. We’re grateful for the help and your support.

South Korea, a nation gripped by one of the steepest population declines on the planet, offers a fascinating paradox. With the world’s lowest fertility rate, it’s tempting to think that as its population shrinks, energy demand would naturally follow suit. Yet, the numbers tell a different story.

In 2022, South Korea ranked as the seventh-largest energy consumer globally, reaching a staggering 547.9 TWh of electricity consumption—a 2.7% increase from the previous year. This surge, despite the declining population, is largely driven by South Korea’s industrial sectors, which are notorious for their emission intensity. To put it simply, South Korea doesn’t just consume energy, it *produces* energy demand. Its per capita energy consumption, which in 2023 stood at 5.6 tons of oil equivalent (toe) per person, is a full 50% higher than the OECD average. And within that figure, electricity alone accounted for 11 MWh per person.

Despite the country’s demographic decline, total energy consumption fell by just under 3% in 2023—a modest dip in the context of a 1.5% average annual increase since 2010. KEEI’s Mid-Term Energy Demand Outlook predicts a 2.3% annual growth in energy consumption through 2025, underpinned by industrial demand. This serves as a stark reminder: population might decline, but energy consumption tied to economic activity remains resilient.

The secret lies in South Korea’s industrial might, where automation has become the backbone of growth. The country boasts the world’s highest ratio of robots to workers, meaning that even with fewer people, productivity—and thus energy demand—has been able to scale.

In short, the future doesn’t see mankind passively watching its standards of living decline. Instead, we adapt and innovate, finding new ways to use materials and energy more efficiently—if not at a faster rate. Population may dwindle, but the engines of industry and technological advancement show no signs of slowing down. South Korea, in particular, is a case study in how economic momentum can outpace demographic trends.

https://www.statista.com/chart/13645/the-countries-with-the-highest-density-of-robot-workers/

A fabulous essay! After reading “ The Frackers” I have more faith than ever the world will innovate and prosper, it’s just going to be a bumpy ride from time to time primarily caused by people who haven’t reviewed history as you just did. The firewood statistics…. Wow, but drive around the rural areas of America and so many people still use wood as their primary fuel source for heat.