Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There!

Overconfidence in our understanding of earth’s systems is not limited to climate.

Man plans, God laughs – old Yiddish proverb

Earth’s coupled non-linear chaotic systems constantly remind us that even with all of the advanced scientific knowledge, enormous computing power, and the sophisticated modeling we possess, our detailed understanding of these systems has large blind spots.

Interconnected components (atmosphere, oceans, land) that mutually influence each other (coupled), outputs resulting from their interactions that are not proportional to their inputs (non-linear), complex, dynamic, and highly sensitive to initial conditions (chaotic), these systems are notoriously difficult to predict. Cause and effect are poorly understood and easily mistaken.

But overconfidence in our scientific understanding of these systems is nothing new. It predated the computer era by decades.

In America, as western settlement expanded, so did agriculture and livestock, as well as hunting wild game for protein. The combination of humans hunting populations of large prey animals and clearing land for livestock increased conflict between humans and predators as the latter began to hunt livestock. Wolves took the brunt of the consequences, but cougars, bears and coyotes were also shot and poisoned. Some of this was done to protect livestock but also in early attempts to manage populations of desirable game species like elk and deer.

Congress created Yellowstone National Park in 1872. For the better part of 60 years after its designation as America’s first national park, wolves, cougars, bears and coyotes were killed inside Yellowstone under the direction of the Park’s administrators and rangers, with full knowledge of the National Park Service’s (NPS) first scientists: As the NPS notes (emphasis added):

When Yellowstone was established in 1872, gray wolves were present. The fossil record also shows their presence in the region going back thousands of years. However, early park managers, lacking an understanding of ecosystems, viewed wolves as destructive predators. Between 1914 and 1926, at least 136 wolves were killed in the park, and by the 1940s, wolf packs were nearly extinct in the area.

By the early 1930’s, the NPS’ policy had changed. Like other managers of his era, NPS Director Horace Albright previously held the belief that wolves were destructive and had no place in Yellowstone, but in his 1931 “National Park Service’s Policy on Predatory Mammals,” he wrote:

“The National Park Service believes that predator animals have a real place in nature, and that all animal life should be kept inviolate within the parks.”

By the 1970s, extensive surveys found no wolves in Yellowstone. But well before that conservation scientists already realized that humans had made a mistake extirpating wolves from Yellowstone.

Ecosystems evolve over eons. Interactions between herbivorous prey animals, their food sources (plants), available water, and predators effect ecosystems in a slow, delicate, evolutionary process that is dynamic and complex. Yellowstone’s higher latitude, arid, alpine ecosystem, shared by large body ungulates (elk, deer, bighorn sheep) and predators (wolves, bears, cougars), across a mix of volcanic and granitic geology, is dynamic and complex.

It is well known that the extirpation of wolves and other large predators from their historic ranges had an effect on plant and animal life and even water table levels and the course of streams in and around Yellowstone National Park. How and the extent to which large predator removal (or reintroduction) has downstream ecosystem effects – a concept known as “trophic cascade” – has been extensively studied and hotly debated by biologists and conservation scientists for decades.

After wolves and significant numbers of grizzly bears were killed in the park at the turn of the last century, Yellowstone reached what biologists call the “alternative stable state” we see today. Beginning in 1995, wolves were released in the park in order to study whether and how their reintroduction might induce a desirable trophic cascade that would return the Park to some prior ecosystem state.

For nearly a century since their shooting extirpated wolves from Yellowstone, biologists have been trying to understand the relationship between large body predators and prey and the Yellowstone ecosystem. Despite enormous advances in science and the power of computer modeling, detailed understanding remains elusive. A recent study demonstrates the difficulty.

In The Ecological Impacts of Large-Carnivore Recovery in North America lead author Chris Wilmers (University of California, Santa Cruz) and three colleagues find that, while it is widely believed that the presence of large predators reduces ungulate populations (e.g. elk, deer, Bighorn sheep) and promotes plant growth through trophic cascades, the actual relationship is “complex, context dependent, and shaped by multispecies interactions, alternative stable states, and especially, human activities.”

The study’s authors conclude that our understanding of the relationship between ungulates, predators and trophic cascades in ecosystems is confounded by human activities:

“The extent to which trophic cascades operate in human-dominated landscapes—where large carnivores are often regulated to persist at or below the social carrying capacity—remains a critical gap in our understanding.”

As Wilmers commented (emphasis ours):

“It’s not that there’s not evidence consistent with a trophic cascade in Yellowstone, it’s that the effects are a lot more complicated and weaker than what was initially thought. Without a clear link between wolf predation and the decline of elk populations, the foundation for a scientific determination of a trophic cascade is too shaky to build upon.”

Asked whether an ecosystem in which humans have driven out large predators can be restored to its pre-extirpation state by their reintroduction, Wilmers does not believe scientists can answer the question. But his recommendation was telling:

“You’d be better off avoiding the loss of beavers and wolves in the first place than you would be accepting that loss and trying to restore them later.”

Coupled non-linear chaotic systems are extremely difficult to model. For these systems, overconfidence in scientific findings relying on computer models can lead to questionable, if not absurd, policies. Aside from the obvious manifestation in “climate change” policy, the issue rears its head in wildlife, conservation, and ecosystem services management.

Recently, two stories about human meddling in ecosystems caught our attention. Both are examples – like “climate change” – where the pursuit of what may be admirable objectives finds fertile ground in studies relying on computer models. And where, on the basis of “the science,” government bureaucrats make decisions that find the benefits outweigh the risks and costs.

Both stories share a basic premise: our best available science suggests we need to kill – by shooting or poisoning, just like the wolves in Yellowstone 100 years ago – some species to protect others.

But are these projects the moral thing to do? Will they even work? Are we attempting to use science to justify manipulating nature to suit a belief or preference? Let’s head out to the American west and consider our arrogance, hubris, and overconfidence in a context other than climate.

Our first story takes us, quite conveniently, to the Yellowstone ecosystem. The Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness (ABW) consists of nearly 1,000,000 acres of rugged, mountainous, remote lands in southern Montana abutting Yellowstone National Park’s northeastern boundary.

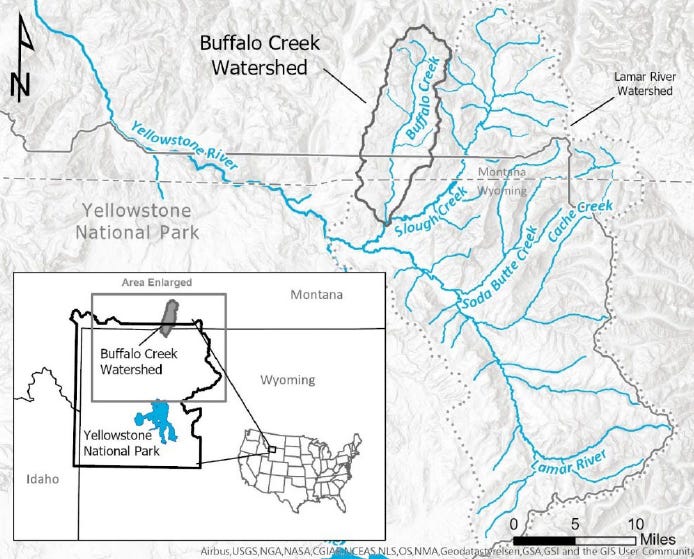

Buffalo Creek drains a large mountain bowl with 10,000-foot peaks in the ABW about 40 miles north of the Wyoming border. Hidden Lake is a small alpine lake whose outflow drains to Buffalo Creek about halfway along its course into Yellowstone National Park.

Once inside the Park, about 3.5 miles south of the Montana/Wyoming border at around 6,500 feet elevation, Buffalo Creek empties into Slough Creek which flows a short distance before emptying into the Lamar River. After meandering a few miles to the west, the Lamar River meets the Yellowstone River, about 25 miles north of Yellowstone Lake. Both rivers are world renowned among fly fishing enthusiasts for the famed Yellowstone Cutthroat trout (YCT), a unique trout species found only in the Yellowstone ecosystem.

In the 1920s and 1940’s, Montana state officials stocked YCTs above a cascade (steep waterfall preventing upstream migration) in the Buffalo Creek watershed in what Congress would later designate as the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, (in 1978, combining the two previously designated primitive areas). In 1932, state officials also stocked several thousand rainbow trout in the same area, including Hidden Lake.

Over the decades since rainbow trout were introduced into Buffalo Creek and Hidden Lake, they naturally found their way downstream and became established in Slough Creek and the Lamar River. There, they developed an amorous relationship with YCTs and began breeding. Today, hybrid rainbow/cutthroats are found in several upper Yellowstone River watersheds.

Studies show that rainbow/YCT hybridization and introgression - the process by which genes from rainbows get permanently incorporated into YCT’s gene pool – has caused the loss of some YCT populations. The interbreeding produces fertile hybrids and backcrosses that progressively replace pure YCT genomes over time. The rainbow trout originating in Buffalo Creek and Hidden Lake from stocking nearly 100 years ago are a documented source population contributing to hybrid trout genes in Yellowstone National Park by its connection to Slough Creek and the Lamar River.

After several years of study, in March 2021 the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) proposed to mitigate this hybridization with a project most “environmentalists” would consider radical inside a designated Wilderness area. FWP proposed to use rotenone, a powerful aquatic poison that kills any organism with gills – from fish to tadpoles - in nearly 46 miles of streams, ~11 acres of lakes (including Hidden Lake and a smaller, adjacent unnamed lake) and about 25 acres of high alpine wetlands in the Buffalo Creek watershed in the ABW.

It is important to note that Hidden Lake and the entire Buffalo Creek watershed were fishless before Montana state officials introduced YCTs and rainbow trout around 100 years ago. The aforementioned cascade in Buffalo Creek near the Yellowstone Park boundary prevented upstream migration of any fish, including native YCTs, into the creek and its watershed in the ABW above.

Because Montana FWP’s proposed action would take place on federal lands, the project required that the U.S. Forest Service complete an Environmental Assessment (similar to an Environmental Impact Statement but for smaller projects in size and scope) and open the plan to public comments. FWP completed the EA in March 2021, and the public comment process the following month.

The project’s primary goal is to remove rainbow trout in the Buffalo Creek watershed to protect the integrity of Yellowstone Cutthroat trout genetics in the Lamar and Yellowstone rivers. But the project has a secondary goal, as the EA notes (emphasis added):

“A secondary benefit of the proposed action is that it would establish a secure population of nonhybridized Yellowstone cutthroat trout in Buffalo Creek. Climate change is constricting the amount of habitat suitable for Yellowstone cutthroat trout within their historic range. The project area is at high elevation and predicted to remain thermally suitable for Yellowstone cutthroat trout for the foreseeable future.”

Poisoning an alpine watershed in a designated Wilderness area to establish a sort of high-altitude “climate” refuge and gene bank for YCTs. (What arrogant human manipulations of nature will computer models be used to justify next?)

In November 2023, environmental non-profit Wilderness Watch sued the Forest Service to stop the project under the 1964 Wilderness Act. Both parties filed cross-motions for summary judgment, and the matter was heard before U.S. Magistrate Judge Kathleen DeSoto in December 2024.

In March of 2025, Judge DeSoto rendered her Findings and Recommendations, recommending summary judgment be granted in favor of the Forest Service. Wilderness Watch filed objections, triggering a review by a U.S. District Court.

The second matter that recently raised our eyebrows takes us to the Pacific Northwest, where federal and state officials have been attempting to protect the Northern Spotted Owl since the 1970’s, well before the species was formally listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1990. Unlike the story of wolves and ungulates or hybridization between rainbow and cutthroat trout in Yellowstone, human interference is not at the root of this dilemma.

In the 1970’s, Barred Owls from the forested east of North America began a westward range expansion, first across the Great Plains and then into western Canada. From there they moved south into Washington, Oregon, and California along forested corridors where they have become established in Northern Spotted Owl territory.

The first thing you would notice if the two species stood side-by-side is that Barred Owls are much larger than their more diminutive cousins. With that size comes strength, and scientists fear the larger, more aggressive barred owls will push the smaller Northern Spotted Owls out of their preferred habitat.

In September 2024, the Biden administration’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) approved a plan for USFWS agents to shoot approximately 470,000 barred owls in the Pacific Northwest, in Washington, Oregon and California, over a 30-year period and at a cost to taxpayers of over $1.3 billion. (Since 2009, federal wildlife agents have already killed about 4,500 barred owls along the west coast.). Federal officials justify the project by deeming Barred Owls as an “invasive species.” Reducing them, in theory, gives Northern Spotted Owls the best chance of recovery.

But some raptor researchers have expressed serious doubts about the ethics of the project. Others question its chances of success, noting that killing Barred Owls in three Pacific Northwest states will not stop their continental expansion. Still others are dubious of classifying Barred Owls as an “invasive species” in the forested habitats where they have simply expanded their range.

Here again, scientists and studies using computer models can find justifications that seem to check all the boxes and follow required processes. But – even leaving the $1.3 billion price tag aside - is shooting one species of owl to save another a good idea? Like the plan to poison a watershed in the Yellowstone ecosystem to save one species of trout from another, this project also has troubling moral and practical implications.

This summer an alliance between environmental and animal welfare interests (somehow) pulled together enough support in Congress to put forth a joint resolution in the Senate to stop the project.

So, where do both of these “environmental” projects currently stand? Oddly enough, the latest twist in both occurred recently, in the same week.

In late October, by a vote of 72-25, the Senate rejected a motion to proceed to a vote on the joint resolution disapproving of the plan to shoot nearly half a million barred owls. For now, your tax dollars will continue to be used to kill Barred Owls with shotguns.

The same week, in a Montana U.S. District Court (Missoula Division), judge Donald Molloy stopped Montana FWP’s plan to kill rainbow trout by rotenone poisoning in Buffalo Creek in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness. Judge Molloy granted summary judgment in favor of Wilderness Watch and vacated the U.S. Forest Service’s August 2023 Decision Notice approving of FWP’s plan, remanding the matter to the agency for further review consistent with his order.

Judge Molloy rejected the Forest Service’s argument that the project would restore natural conditions in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, finding that because Buffalo Creek was naturally fishless above the cascade near its border with Yellowstone National Park, “the wilderness neither depended on Yellowstone cutthroat trout for ecological balance nor contributed them to the watershed as a whole. As a result, conserving them serves no wilderness purpose.” Molloy held the project violated the Wilderness Protection Act on several grounds, commenting that:

“Unlike other resource management statutes, the Wilderness Act is not merely a procedural checklist or a delegation of discretion to a managing agency to weigh competing uses; the Wilderness Act mandates the preservation of wilderness character. By failing to consider whether the actions of fish poisoning or fish stocking serve that mandate, the Forest Service’s decision to approve the project was arbitrary and capricious.”

We read Judge Molloy’s decision and grounding legal analysis in relation to the Wilderness Act. It is not obvious if or how Montana FWP and the U.S. Forest Service could alter the plan to undertake the project.

We close by drawing attention to an uncomfortable reality. In his ruling in favor of Wilderness Watch in the Buffalo Creek case, Molloy wisely commented (emphasis ours):

“It is unclear how the elimination of one of those species in favor of another, in a stream neither originally inhabited, preserves the “primeval” wilderness character, or the baseline wilderness character at the time of (the ABW) designation. Rather, as argued by Wilderness Watch, “this is not ecological restoration – it is continued manipulation.”

Given our experience managing wildlife and ecosystems in Yellowstone, humans might take a step back and consider our “mastery” of earth’s coupled non-linear chaotic systems. Armed with the most powerful computers and sophisticated computer models, scientific knowledge, chemical and mechanical tools in human history, scientists have recently put forth other ideas in order to “improve” conditions on planet earth:

Dispersing sulfate aerosol particles into the stratosphere in order to reduce solar radiation reaching the surface and cool earth’s atmosphere.

Dumping enormous quantities of dissolved iron sulfate in the world’s oceans to stimulate the growth of phytoplankton which absorb atmospheric CO2 during photosynthesis.

Earth’s coupled atmosphere-ocean-terrestrial climate system is more chaotic and non-linear than our planet’s terrestrial ecosystems. Yet the overconfident, advanced apes who can’t even clearly understand flora/fauna relationships and trophic cascades in Yellowstone after 100 years of study now seriously consider the most radical intentional geoengineering schemes -Stratospheric Aerosol Injection and Ocean Iron Fertilization – humans ever devised, both relying on computer models. Let that sink in.

We have known how to conserve fish, wildlife, and ecosystems for decades: Protect giant landscapes of critical habitat and valuable ecosystems. Don’t tinker with predator/prey populations. Don’t introduce non-native species. Restrict human access and activity. Use the powers of modern science and computer models to monitor and study these areas carefully, over long-time scales.

But recognize the coupled non-linear chaotic nature of these systems and respect the limits of our knowledge. Do not be quick to use “the science” to justify their manipulation.

When we identify a perceived or actual problem, proceed with great caution. And where the “solution” seems morally questionable, and the pragmatic chances of success are in doubt despite what the model suggests, don’t just do something, stand there!

“Like” this post or we’ll reintroduce wolves in your neighborhood.

Leave us a comment. We read them all and respond to most. Refills the tank here.

Subscribe to environMENTAL for free below.

Share this post generously. Helps us grow. We’re grateful for the assist.

Excellent article! I have live through the same scientific hubris 2000 miles away on the east coast of North Carolina in the Cape Hatteras National Seashore recreation Area, where the NPS and USFWS engaged in "predator control" methods in vain attempts to help beach-nesting avian species, the "Piping Plover" in particular. Enviro groups sue the NPS over them allowing recreational ORV driving on the beach, claiming that it was driving the PIPL to extinction. The NPS amended their rules and closed huge swaths of beach to all human access, and guess what happened? The predators that the humans used to run off now had free reign to attack the eggs and young, and the fledge rates went down, so they started killing all foxes, nutria, and even ghost crabs in the closed areas. And now almost 15 years after the closing of prime fishing areas to all humans and the killing of predators, the PIPL fledge rates are still right where they were prior to all this nonsense. You should dig into this topic if you have the time, and be astounded!

Science is observing, questioning, recording, communicating. Our knowledge is like a sphere where the more we know, the contact with unknown increases. People are blinded by their believe in linear causality. They use machines to find trends that are not obvious and conclude if things don't change the trend will become a problem. However, change is the one constant in living systems. The tragedy of the barred owl in the Pacific Northwest is the result of our belief in survival of the fittest. The law of nature is organisms that cooperate will thrive much more than those that compete. Barred owls are not likely to displace spotted owls. Any more than in Eastern forests, great horned owls displace barred owls. They have niche differentiation. Stop owl discrimination.