“A conservationist is one who is humbly aware that with each stroke [of the axe] he is writing his signature on the face of the land.” - Aldo Leopold

It’s late July in Wyoming’s Yellowstone National Park. A young family of dedicated environmentalists stares in wonder out of the window of their motor home as a Grizzly bear sow and her two cubs frolic in the gray light of dawn in an alpine meadow. Fifty miles away, in the Absaroka range of the Shoshone National Forest, a group of lifelong friends stand with fly rods in hand at the edge of a crystal clear high altitude mountain stream. They buzz with excitement as they survey hordes of Cutthroat trout rising to Blue-Wing Olives.

It's early December in Texas at the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge. An elderly woman, a lifelong Audubon member, tears up as she stands at the very spot where she and her late husband first kissed as the sun set and neotropical birds flew to their evening roosts. Earlier that morning on Florida’s Space Coast, a father wiped away tears of joy and gratitude at sunrise where he had taken his late father on his last duck hunt and now his young son on his first.

Americans are blessed with an incredible bounty of National Parks, National Forests and National Wildlife Refuges. Millions of American enjoy outdoor recreation on these lands. For many of us, the connection is much deeper, passionate, even spiritual.

The vast expanse of the North American continent combined with the United States’ unique geography creates a setting unparalleled anywhere else on earth: On a single summer day, wilderness campers at the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska may encounter a Polar bear, while at the farthest opposite end of the continent scuba divers at the Biscayne National Park witness a colorful display of tropical fish in the Florida Keys.

The combined network of U.S. National Forests, National Parks and National Wildlife Refuges today encompasses over 428 million acres. For perspective, that area is ~2.5 times the size of Texas and equal to about 1/6th of Europe’s total landmass.

America’s history of wildlife preservation and stewardship (and screwups) is legendary. Whitetail deer and wood ducks were hunted nearly to extinction at the turn of the 20th century. Today, their populations are at or near historically high levels.

Wildlife do not recognize human boundaries, particularly migratory waterfowl. A mallard hen fledged near Rice Lake, Saskatchewan (Canada) may cross half a dozen or more U.S. states before arriving on her wintering grounds in Arkansas. Ducks and geese may use a combination of private, state and federal lands across hundreds of square miles in a single day during their migrating and wintering periods.

Fish and wildlife conservation and management occurs over large scales. A wide variety of habitats and ecosystems are required to meet the full life-cycle needs of terrestrial and avian species.

The most successful, intensive, and effective conservation activities in the U.S. occur on private lands, some with the assistance of State and Federal agencies. Land disturbances across vast landscapes – even on private lands - have significant consequences for fish and wildlife.

Whether you are an avid conservationist who lives to hunt and fish or you merely appreciate nature’s views, most of us value healthy ecosystems, abundant fish and wildlife, and clean air and water. Regardless of political affiliation, ideology or lack thereof, these shared values should be a place where even the most hardened conservatives and liberals, Democrats and Republicans find common ground.

But energy, environmental and economic policies are complex, nuanced and intertwined. Even when consensus among parties is achieved, the law of unintended consequences makes outcomes uncertain. 2022 proved this reality the hard way for Europe.

Hidden from “Plain” view is how U.S. biofuels-related policy impacts wildlife and ecosystems. As political parties and ideologues bludgeon each other over climate change policies, the destruction of wildlife habitat is the story that flies largely under the radar.

Corn ethanol underpins current U.S. “renewable fuels” policy. A fuel alcohol made from corn, corn ethanol is chemically very similar to the moonshine made famous during prohibition.

Consider the irony that whiskey stills (for making moonshine) are painstakingly hidden from law enforcement while industrial scale moonshine operations (for making ethanol) are out in “Plain” view, given subsidies and held out to be a solution to “climate change”. And all the while, much of our prime wildlife habitat is getting hammered by this moonshine.

In our last post, we noted the “Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007” (EISA) as the political and legislative genesis of the “renewable fuel standard” (RFS) and ethanol. Aside from the moral question of using food for fuel (~40% of the U.S. corn crop is used for ethanol production), we highlighted numerous environmental-related consequences including:

fertilizer/pesticide use

nitrogen loading to waterways and resulting contribution to the annual summer “dead zone” (hypoxia) in the Gulf of Mexico

water inefficiency, the drawing down of critical drinking water aquifers

But the roots of ethanol in the U.S. actually predate the “Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007”. Human health and environmental risk were the initial drivers. Here is the Reader’s Digest version.

Oxygenates cause gas to combust more efficiently, emit fewer harmful tailpipe emissions, and reduce smog/ozone. In 1979, methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) replaced lead, a known neurotoxin, as the oxygenate in U.S. gasoline.

By the mid-1990s, MTBE began to cause significant environmental concerns of its own. Impacts to groundwater resulted mostly from leaking underground storage tanks and piping systems at filling stations. In 2000, EPA drafted plans to phase out MTBE over four years.

The 2005 Energy Policy Act was the proposed solution, removing the gasoline oxygenate standard and replacing it with the present RFS. We substituted ethanol for MTBE as the oxygenate in the U.S. gasoline supply. It was sold as part of both “energy independence” (Republicans) and “renewable energy” (Democrats).

The RFS and ethanol began a new era of biofuels and green grift. EISA required 36 billion gallons of ethanol in the U.S. fuel supply by 2022. Corn was never intended to provide all of it, because cellulosic ethanol (ethanol from plant fiber, not corn) was supposed to eventually grow, and rapidly. Yet here we are in 2023 with corn comprising the feedstock for 94% of U.S. ethanol production. Billions of taxpayer dollars have gone into cellulosic ethanol R&D, but it was always at best a hope and at worst a pipe dream.

Initially signed by a Republican President, the 2007 RFS has since been maintained by every Congress and President, Democrats and Republicans. It is fair to say at this point that both parties now own its consequences.

A 2019 report from the National Wildlife Federation titled “New Research Findings Link Biofuel Mandate to Environmental Harm” noted:

More than 10 million acres were converted to crop production for ethanol between 2008 – 2016

2.2 million acres of likely native prairie destroyed

Higher crop prices due to biofuel demand led farmers to plant on 1.6 million new acres, putting land in crop production that otherwise would have likely gone into a conservation program or been left fallow as pasture.

Created by Congress in the 1985 Farm Bill and administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) targets conservation on private lands. It has taken a hard hit as a result of the 2007 RFS and “the ethanol mandate”. Under CRP (emphasis added):

“In exchange for a yearly rental payment, farmers enrolled in the program agree to remove environmentally sensitive land from agricultural production and plant species that will improve environmental health and quality. Contracts for land enrolled in CRP are from 10 to 15 years in length. The long-term goal of the program is to re-establish valuable land cover to help improve water quality, prevent soil erosion, and reduce loss of wildlife habitat.

CRP lands have provided vital habitat for a wide variety of game and nongame wildlife species for almost four decades. They deliver valuable “ecosystem services” including reducing soil erosion, reducing fertilizer application (and corresponding nitrogen and phosphorous loading to surface waters), groundwater filtration and aquifer recharge, build soil nutrients, and sequester CO2.

But when the 2007 Energy Bill ramped up corn ethanol production, farmers understood the economics all too well and when their CRP leases expired, many chose not to renew. USDA came under lobbying pressure to eliminate CRP early lease termination fees.

In 2007, annual U.S. biofuel (mostly ethanol) subsidies were $3 billion. By 2013, they had grown to over $7 billion annually. CRP was crushed.

At its peak, CRP conserved almost 37 million acres of land, an area larger than the state of New York. More than 13 million acres have been lost, an area almost as large as the state of West Virginia. Over 4.6 million acres have been lost in the ten largest corn-producing states alone, an area about one-third larger than the state of Connecticut. In Kansas alone, CRP loss exceeds 1.3 million acres.

In 2016, EPA and USDA scientists estimated that ~30% of expiring CPR leases were converted to intensive agriculture in the three year period from 2010 – 2013. The study’s author’s note (emphasis added):

“We found no evidence that expired CRP lands shifted in large percentages into other set-aside conservation programs, either federal or non-federal; rather, as noted above, only 3% of expired CRP land remained under a comparable level of conservation protection.”

Many CRP lands produce prolific numbers of wildlife. Ducks Unlimited estimated that between 2005 and 2011 (before the worst impacts of the ethanol mandate), “CRP lands produced an additional 1.5 million ducks each year.”

According to Pheasants Forever, “at CRP’s peak acreage in 2007, there were an estimated 11 million pheasants in South Dakota.” The South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks estimated 11.9 million that year. The figures fluctuate from year to year, with rainfall a key component, but it appears pheasant populations in South Dakota have not exceeded 10 million since 2008.

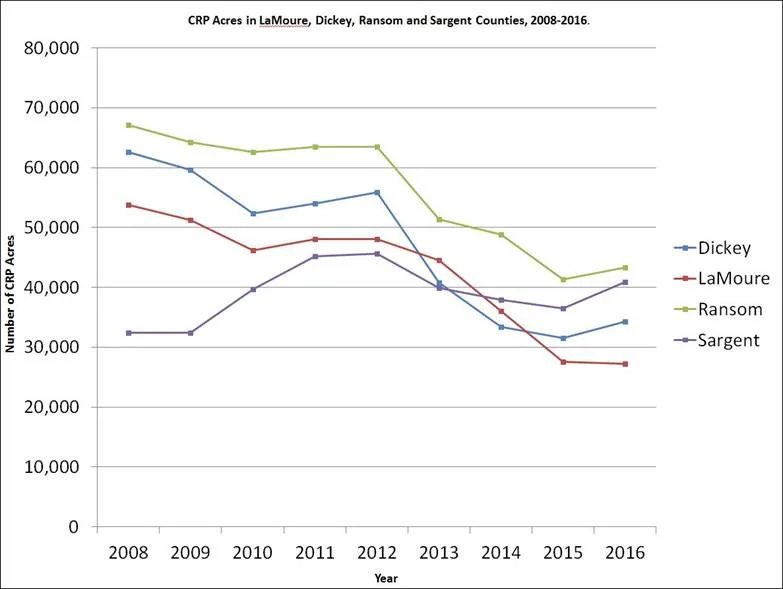

The situation appears largely the same in North Dakota. This table shows heavy CRP losses in four northeastern counties:

No one knows the full impact on wildlife from lost CRP acreage. However evidence abounds that the consequences are significant. A 2019 article in the Journal of Environmental Management evaluated how landscape characteristics and winter severity influenced white-tailed deer occurrence and abundance across North Dakota. While noting that CRP lands also benefit mule deer and pronghorn, the report noted (emphasis added):

“With more than 90% of surface area of North Dakota being in private ownership and the ongoing conversion of native habitats to crop production and energy development, programs such as the CRP will be fundamental to sustaining populations of white-tailed deer that can meet recreational demands.”

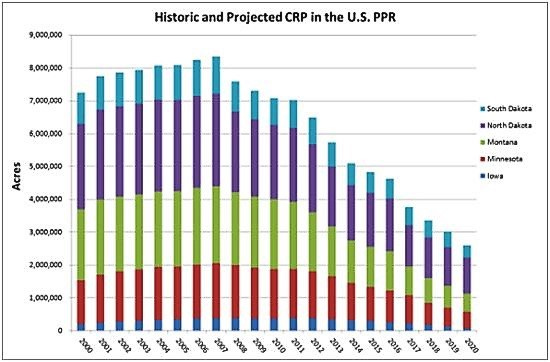

Wetlands on CRP lands are a vital component of waterfowl production in the “prairie pothole region” (PPR) of the United States. The PPR, known for years as the “Duck Factory of North America”, is a landscape of tens of millions of acres of small pothole ponds and sloughs in the Northern U.S. Plains and central Canada. The PPR also happens to be the heart of CRP country.

The graph below shows what happened to CRP enrollment in the key U.S. PPR states of North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa and Montana since 2000. Note the peak is concurrent with the 2007 Energy Bill and the ethanol mandate:

How does loss of CRP land in the PPR “Duck Factory” impact continental waterfowl populations and ecosystem services? According to research from the world leader in wetlands conservation, Ducks Unlimited (emphasis added):

CRP was responsible for 25.7 million additional ducks produced in the U.S. Prairie Pothole Region during 1992-2003.

Since 1986, CRP has reduced more than 8 billion tons of soil erosion – the equivalent of approximately 267 million large dump truck loads of dirt.

In 2010, CRP waterway and riparian buffers helped filter 365 million pounds of nitrogen and 72 million pounds of phosphorus from entering our nation's lakes, rivers and streams. (editors note: the load in the MS river contributes to the Gulf of Mexico hypoxia or “dead zone”)

In 2010, CRP helped capture and store 52 metric tons of carbon dioxide.

CRP lands also reduce downstream flooding by absorbing and slowly releasing storm water.

Additionally, a USDA informational document states that (emphasis added) “CRP contributes to a net increase of an estimated one million ducks per year.” Waterfowl conservation organization Ducks Unlimited has estimated the figure at two million per year.

In 2012, the U.S. Department of Interior and the U.S. Geological Survey recognized the challenges facing CRP, and produced a report, a sentence from which succinctly validates what has haunted us for more than a decade:

“The ecological costs of putting existing conservation lands into corn production for ethanol exceed the environmental benefits realized.”

Ironies abound.

While

regressiveprogressive environmentalists lament over the earth’s “carrying capacity”, they drive policy that threatens what they claim to hold so dear. Loss of CPR acreage from ethanol endangers wildlife populations, ecosystems and their carrying capacity.The train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio ignited panic about hazardous materials traveling by rail. We pushed out MBTE because it was dangerous. Maybe that was good, maybe that was bad. What we do know is that MTBE used for gasoline was distributed through pipelines not by rail. Then we mandated ethanol replace MBTE. And how does virtually all ethanol produced get transported? By rail or tanker trucks. Imagine that.

Drought in the Plains states is attributed to human emissions of CO2 from burning fossil fuels. The solution? Use three gallons of water to make one gallon of ethanol. Draw it from an already threatened aquifer (the Ogallala) using giant center-pivot irrigation systems to water corn on land that had been lying fallow in CRP. Genius.

Environmentalists screech when 12 ducks land on an unlined oil lagoon in west Texas. Meanwhile, they promote biofuel policies that reduce duck and pheasant populations by around 1 million ducks AND 1 million pheasants per year. At least.

(The coup de grace:) In November 2022, USFWS listed the lesser prairie chicken as an Endangered Species in the northern portion (and a Threatened Species in the southern portion) of its remaining range. The rule notice in the Federal Register notes “the primary threat is the ongoing loss of large, connected blocks of grassland and shrubland habitat.”

Regarding the lesser prairie chicken, despite many years of fossil fuel and renewable energy interests accusing each other of being the cause of this habitat loss, the findings in the ESA ruling for the beleaguered species help round out and close our story. We summarize the key findings below:

The largest single source of loss of lesser prairie chicken habitat - crop conversion - directly relates to the ethanol mandate and the corresponding reduction in CRP lands. But wind energy AND oil and gas development have also played a measurable role. The saga of the lesser prairie chicken proves exactly how hard it is going to be to balance environmental concerns, energy reality, economics and basic human necessities like food and water.

As our favorite Substack author, Doomberg often states, “there are no solutions in energy, there are only tradeoffs.”

Corn ethanol. Brought to you by Charlaticians™ in both parties, with little to no understanding of critically important science or economics, making decisions on passions, polls and ideologies.

We can hardly see a better foundation for setting aside partisan differences and starting to solve the very real and steep physics, economic and environmental challenges facing humanity’s energy future: wildlife.

We need oxygenates to reduce tailpipe emissions. We decided we don’t want MTBE. Biofuels sounded easy, were politically doable, and had constituencies and no lack of funding on both sides of the aisle.

As the Great Green Chicken noted on Emmet Penney’s Nuclear Barbarian’s podcast recently, “All of this is just Cos Play”.

Bipartisan Cornflakes™ (ethanol), Spinning Green Crucifixes™, and Evil Fossil Fuels all have tradeoffs. Sometimes even when the two sides can agree, their “solution” has negative unintended consequences, only evident to both later.

In this “environment” is it any wonder some ducks and chickens would get hammered in the process? We hope more Americans Cry Fowl.

It remains true that currently the biggest danger to wildlife habitat is renewables; wind, solar and biofuels.

The energy density is so low the only way to utilize them is to take over large swaths of land to harvest them.

I have developed an almost intractable belief that none (NONE) of the people behind all the “impassioned voices” from various political camps care one BIT about any of the environmental issues they shriek about.

At best, they are Charlaticians™. At worst, they are rapacious sociopaths, willing to say or do anything for their own personal benefit.

Many other political realms suffer from similar malignancies, but I think the area of environmentalism is likely the worst of the worst. The long term consequences are probably greatest, the money potential for grift is staggering, and people’s innate passion for nature blinds them to hard truths. This Substack is one of the few sources left that are worthy of respect. Long (and loud) may you continue.