An Offer You Can’t Refuse

New York’s new Sopranos style climate law uses a novel confiscatory approach.

Giving money and power to government is like giving whiskey and car keys to teenage boys. - P. J. O'Rourke

Consider this hypothetical scenario. You are the CEO of a national fast-food restaurant franchise with hundreds of locations in New York. You and your industry are constantly being bombarded by state health officials about your contribution to obesity and its impact on the health of the state’s citizens.

The same state health officials do not seem to be interested in the contributions other food and beverage establishments are making to the very same problems, and whether they make ice cream, donuts, candy, or beer. The focus is on you - the fast-food industry.

Now, suppose that today, the State of New York passes a law making the 5 largest fast-food chains with annual sales in the state between 2000 – 2018 above an arbitrary threshold legally liable for causing past, present, and future obesity in New York citizens. Imagine if that new law demanded money damages from these 5 large fast-food companies for the health impacts on citizens its medical systems has treated, is treating and will treat, even if many other food companies in the aggregate contributed far more to the overall problem, or that the damages demanded by the state turned out to be badly overestimated.

Remember, of course, that all of these fast-food companies’ activities were legal and their products were in demand from consumers during the period 2000-2018. But our theoretical New York law would retroactively deem them illegal and impose penalties today, in 2025. Worse, because our theoretical law operates on the basis of strict liability, no finding of fault would be necessary to compel these companies to pay whatever fines or penalties the State demands.

Beyond the pale? Not in the minds of the regressive progressive Charlaticians™ in New York. In fact, a recently passed law suggests that the “leaders” in New York have even higher aspirations than just saving the state’s citizens from health risks. And they intend to use the force of government in pursuit of it.

Which industry is the latest target of New York’s statutory shenanigans? And what novel approach have the state’s political “leaders” taken in their latest confiscatory concoction? Let’s have a look at New York’s new history-making law that has to have Gavin Newsom and California state Charlaticians seething with jealousy for not having thought of it first.

We begin our story with a necessary but brief overview of the federal environmental law on which the newly passed New York legislation is modeled. The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA) is the U.S. federal law designed to hold owners/operators liable to investigate and remediate (clean up) of “hazardous substances” (as defined) at sites representing an imminent and substantial endangerment to human health and the environment.

CERCLA created the Hazardous Substance Response Trust Fund, which imposed a tax on industry based on volume for certain types of chemical and petroleum compounds. This became known as the “Superfund” and today most people associate that name with the law itself. The original five-year tax was extended two times but expired at the end of 1995. Congress actually reauthorized the tax in the 2021 Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act (and doubled the previously expired rates, for good measure).

Congress passed Superfund in the wake of several notorious industrial contamination incidents, not the least of which occurred in the 1970s at Love Canal, in a residential neighborhood built on an old industrial chemical dump near Niagara Falls, New York. The hazardous substances which fall under the law’s purview are generally the most toxic and carcinogenic to human health, fish, animals, and the environment.

Administered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Superfund gives the agency the authority to compel “potentially responsible parties” (PRPs, defined in the law) to clean up sites under the equitable principle that the “polluter pays.” Where no viable PRP exists (typically due to insolvency), the Hazardous Substance Response Trust Fund pays for EPA to engage contractors to clean up sites.

CERCLA liability is somewhat unique in federal law in three manners. First, Superfund liability is “retroactive” (and yes, that it as bad as it sounds).

Activities that led to releases of hazardous substances that were lawful at the time (disposal, release, etc.) trigger liability under CERCLA. As such, PRPs are held liable for past “lawful” (if dreadful) actions.

Second, Superfund liability is a form of “strict” liability, which does not rely on a finding of negligence. Under the legal concept of strict liability , if you did “___” (even if it was lawful at the time) you are legally liable.

Third, Superfund imposes joint and several liability on PRPs. If ten corporations contributed hazardous substances to a Superfund site, and nine of the parties are financially insolvent, CERCLA gives EPA the authority to impose the investigation and remediation responsibility on the one remaining solvent party.

Finally, Defenses to CERCLA liability exist but are extremely limited. Innocent landowners and contiguous landowners (exemptions that require specific due diligence be conducted) who did not cause or contribute to or exacerbate the release are granted relief. Lenders who only hold title to protect a collateral interest in commercial real estate loans and do not violate certain operational limitations do as well. And PRPs have legal standing under the law to try and collect sums from other entities who may have contributed to the hazardous substance release that caused their liability for site investigation and cleanup.

Superfund is a law designed to address actual contamination involving a quantifiable, imminent and substantial endangerment to human health and the environment effecting soil, surface water, sediment and ecosystems. Why is it relevant here?

Because that federal law – and the legal concepts underpinning it - is the basis for the most creative attempted money grab under the auspices of “climate change” any regressive progressive U.S. state has attempted to date. And it was probably not chosen by accident.

In a new law signed by New York Governor Kathy Hochul on December 26, 2024, the State of New York goes full Sopranos by attempting to use the federal Superfund framework in the context of “climate change” to extract money from oil and gas companies for past lawful activity by government force. If successful, it would force several major energy companies to pay $75 billion for past, present, and future “climate change” damages, adaptation, and other related infrastructure projects in the state.

The “Climate Change Superfund Act” borrows legal concepts from CERCLA. It creates “responsible parties” and explicitly incorporates both retroactive and strict liability. It incorporates a form of joint and several liability to ensure successor liability would follow any firm who acquired an entity with liability after the 2000-2018 “covered period” for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions defined in the law.

The law, officially S.2129-B/A.3351-B, starts out with the usual pablum that climate change causes basically everything, all of it damages New York, and it is 100% caused by GHG emissions from human combustion of fossil fuels. We’ll spare you those details but those interested in them can read the bill here.

In an attempt to justify using the Superfund-type legal framework, New York legislators reasoned the state has previously adopted programs like the inactive hazardous waste disposal site (state superfund) program and the oil spill fund that employ the “polluter pays” principle. It is instructive to note that virtually every other state has similar hazardous waste and/or oil spill (from storage tanks) programs and exactly none have ever tried to apply the strict and retroactive liability framework to GHG emissions from oil, gas, and coal companies. The law proudly notes that “No similar program exists yet for the pollution of the atmosphere by greenhouse gas buildup as a result of burning fossil fuels.”

Among other premises, New York’s Climate Superfund law relies on the idea that it is now possible to determine with great precision the portion of GHGs emitted by individual oil and gas companies over many decades. Accordingly, the law attempts to “assign liability to and require compensation from companies commensurate with their emissions.” How?

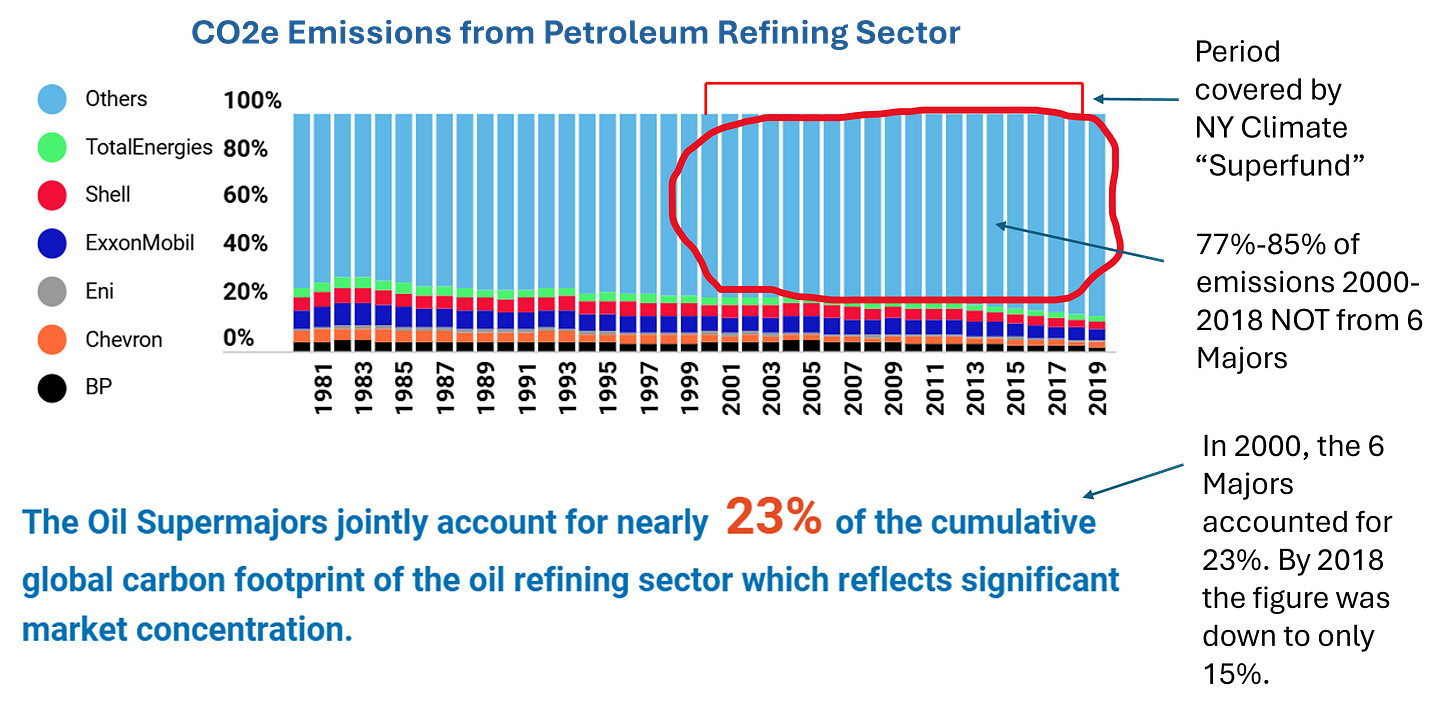

The Columbia Center for Sustainability Investment (CCSI) is a joint center of the Law and Climate Schools at Columbia University in New York City. Its March 2022 report How Much Have the Oil Supermajors Contributed to Climate Change attempts to show what portion of the GHG emissions from the petroleum refining and sales sector over the period 1980 – 2019 come from the world’s largest oil and gas companies. The report breaks down the emissions of the 6 “Supermajors” (BP, Shell, Exxon, Chevron, Total, and Eni) versus “all others”, nominally in million metric tons (Mt) and on a percentage basis. We suspect the state of New York’s “Climate Superfund” bill relies on this CCSI report to allocate historical GHGs to major oil companies.

But in the process of condemning (specifically) western energy majors, the CCSI report actually says the quiet part out loud, unintentionally and rather graphically displaying one of the New York Climate Superfund Act’s central problems in rather convenient fashion.

We downloaded the CCSI data and ran the figures for the “compliance period” in the New York “Climate Superfund” law, overlaying our notes in the right margin. See if you can spot the elephant in the room:

Over the law’s “covered period” (2000-2018), GHG emissions from oil and gas entities not including the Major 6 contributed from ~77% to ~85% of all such emission from refining.

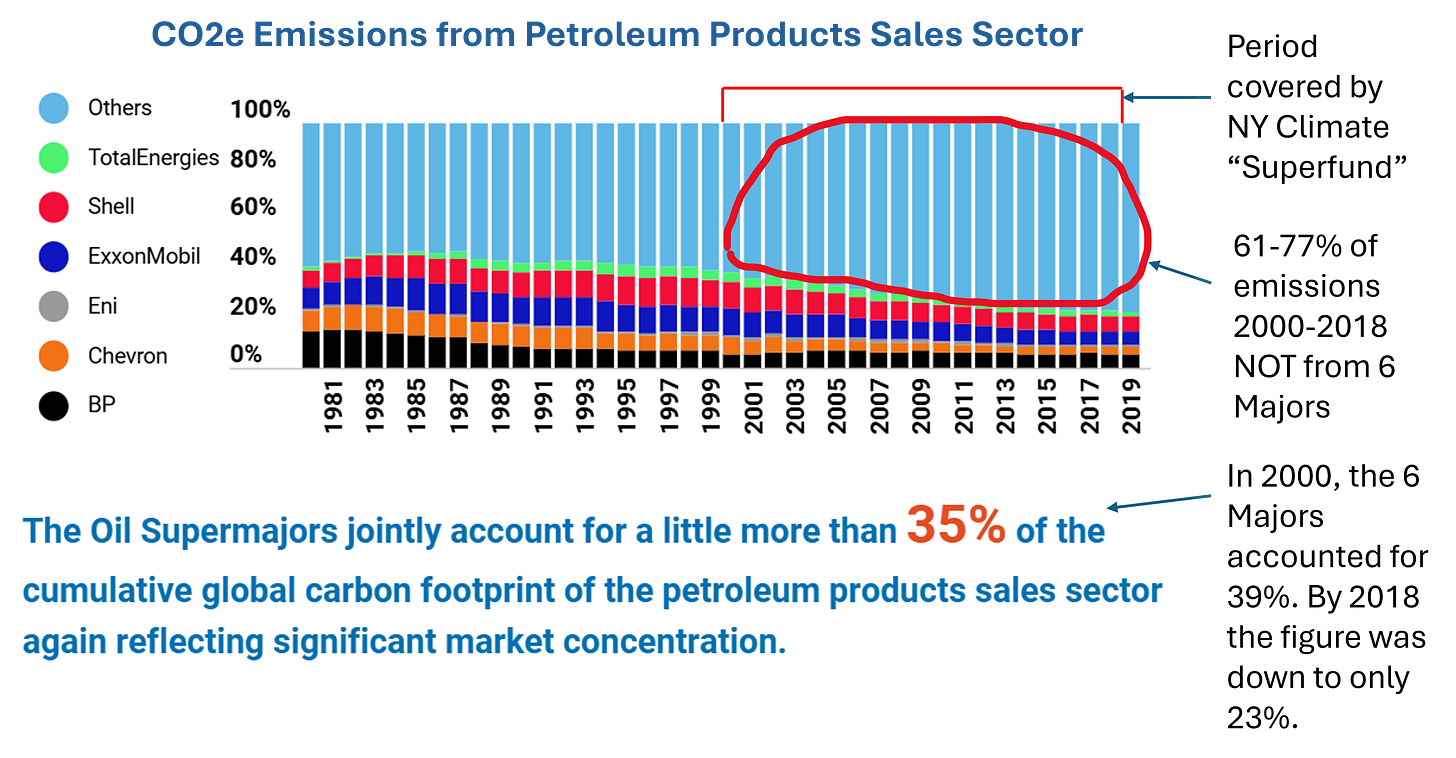

For petroleum sales the situation isn’t materially different, as the chart below shows:

As the CCSI study shows, even for petroleum products sales, oil and gas companies other than the Supermajor 6 contributed the lion’s share of the emissions. But as the legislation notes, the state only intends to pursue recovery from those oil and gas companies with a sufficient connection to the state to satisfy the “nexus requirements of the U.S. Constitution.”

Much of the “damages” claimed by New York depicted in the blue bars we have circled are from State-owned oil companies in Russia (e.g., Rosneft and Gazprom), China (CPNC, CNOOC, Sinopec), Saudi Arabia (Aramco), UAE (ADNOC), Iran (NIOC), Venezuela (PDVSA) and others. Other sources include western energy companies below the size of the 6 Supermajors. Under the legislation, some portion of the six western oil majors will be held responsible and charged for all of these emissions and any correlated damages, to which they have no nexus whatsoever.

The means by which New York’s Climate Superfund Act proposes to allocate responsibility among the six oil majors seems straightforward enough:

“With respect to each responsible party, the cost recovery demand shall be equal to an amount that bears the same ratio to seventy-five billion dollars as the responsible party's applicable share of covered greenhouse gas emissions bears to the aggregate applicable shares of covered greenhouse gas emissions of all responsible parties.”

The legislation exempts the first one billion metric tons of GHG emissions from the extortion penalty levied on the major oil companies. We doubt its authors could have specified the manner in which the legislation proposes to calculate those levies without getting some help from their friends at Columbia University:

In determining the amount of greenhouse gas emissions attributable to any entity, an amount equivalent to nine hundred forty-two and one-half metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent shall be treated as released for every million pounds of coal attributable to such entity; an amount equivalent to four hundred thirty-two thousand one hundred eighty metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent shall be treated as released for every million barrels of crude oil attributable to such entity; and an amount equivalent to fifty-three thousand four hundred forty metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent shall be treated as released for every million cubic feet of fuel gases attributable to such entity.

The legislation spells out New York’s permissible uses for the $75 billion the state hopes to extract from major energy companies. The list includes the usual types of projects one would expect legislators to include when using OPM (other people’s money) to rebuild infrastructure, but the one we have highlighted below does not inspire confidence that all sorts of projects will not magically be declared “climate-related ‘infrastructure’ projects”:

“new or upgraded infrastructure needs such as coastal wetlands restoration, storm water drainage system upgrades, energy efficient cooling systems in public and private buildings, including schools and public housing, support for programs addressing climate-driven public health challenges, and responses to extreme weather events, all of which are necessary to protect the public safety and welfare in the face of the growing impacts of climate change.”

The law is certain to face legal challenges. We would not be surprised to see these eventually reach the United State’s highest court.

While we are not Constitutional law experts, we surmise that two hurdles will be very difficult for the state of New York to overcome in litigation. The first is the allocation issue described above. Because the law exempts from the definition of “responsible party” those entities that do not have a sufficient connection to New York to satisfy the U.S. Constitution’s nexus requirements, it essentially forces five or six U.S. and European domiciled oil and gas companies selling products in New York to pay for “climate damages” for which the world’s other industry firms’ GHG emissions are overwhelmingly responsible by comparison.

The second issue is the question of the damages themselves. Delineating damages attributable to natural variability from those attributable to human emissions of CO2 and other GHGs is far more difficult than the state’s formulaic calculation of GHG emissions from the sale of oil and gas and petroleum refining.

We close with two bits of information that anyone with access to the internet could have easily found which inform our analysis of what the New York Climate Superfund law is really all about.

In 2022, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) produced a series of reports looking at each state’s infrastructure, using eight criteria: capacity, condition, operation and maintenance, public safety, funding, future need, resilience, and innovation. The report’s Executive Summary notes (emphasis ours):

New York State earned an overall grade of C compared to C- in 2015. While this indicates an improvement, the state’s infrastructure is still in mediocre condition. New York’s transportation network, especially in the New York City metropolitan area, is under immense strain in the context of an environment where needs outweigh available funding.

The image below from the report captures ASCE’s New York Infrastructure Scorecard on a single page:

A bit of further research led us to the New York State Comptroller’s Report on the State Fiscal Year 2024-25 Enacted Budget Financial Plan issued just six months ago. The report’s first page notes the state’s projected budget deficit over the next three state fiscal years (SFY) (emphasis added):

The divergence in projected growth between receipts and disbursements results in a cumulative projected budget gap totaling $13.9 billion between SFY 2025-26 and SFY 2027-28.

So, the state’s infrastructure is in desperate need of funding for repair, it has a projected three-year budget deficit that works out to about $4.6 billion annually, and a new Climate Superfund law in which a search for the term “infrastructure” conveniently returns 13 results in a 13-page law.

Combining the bill’s wording around “infrastructure” with the State Comptroller’s July 2024 budget report which projected a $13.9 billion budget deficit over the next three years, you could be forgiven for speculating that New York’s new Climate Superfund law looks like an attempt to force the oil and gas industry to pay for neglected state infrastructure it can’t afford to maintain or replace, all wrapped in climate change virtue. Bada-Boom, Bada-Bing!

We expect that the chances New York legally recovers $75 billion through its new Climate Superfund law are Slim and none. And Slim took the 4:05 Amtrak to Boston.

But we do chuckle at the prospect that California legislators, who pride themselves on outgreening every other state, didn’t think of this first. And that Governor Newsom is green with envy for being climate upstaged by the governor of another regressive progressive state without the political capital or panache. Hair gel and good looks will only carry a guy so far, Big Guy.

“Like” this post to make Gavin Newsom jealous he got punked by New York.

Leave us a comment. We read all of them. Refuels our internal combustion engine.

Subscribe to environMENTAL for free below.

Share this post. Helps us grow. We’re grateful for that. Who knows….might even help reduce energy blindness, EcoStatism, and neo-Malthusianism some day.

green with envy 🤣

I suggest those 6 companies simply exit NY state completely until the lawsuits are concluded. My take is Governor Hochul will have much bigger problems on her hands if the citizens of NY can no longer by gasoline/diesel/heating oil to warm themselves in the winter or drive where they need to go.

If I were those companies, I’d hold a joint news conference: “We have an obligation to both our share and our fine customers in New York State.”

The NYS legislature has 90 days to overturn this onerous legislation. After that period, if this statute is not overturned, we will withdraw all sales of hydrocarbon products in the state.

We do not wish to harm any of our fine customers, but we cannot in good conscience continue to sell our products in a state where legislators hold us responsible for global conditions far beyond our responsibility.

We urge all state legislators to carefully consider the needs of their constituents before allowing the rash consequences of what they have wrought.

The conduct of modern society depends upon the use of hydrocarbons. We again urge NYS legislators to carefully consider all aspects of this unfortunate situation.”